German artist Tilmann Krumrey has creativity running through his veins. He was born into a family bursting with artistic personalities and inherited a Bauhaus aesthetic from his father Immo Krumrey. Krumrey (b.1966 in Frankfurt a.M., Germany) caught the art bug at the age of 7 when he visited the studio of sculptor Doris von Sengbusch-Eckardt, a sister of his grandmother.

After studying History of Art and switching to Economics, Krumrey gained an MBA and worked in marketing, advertising and venture capital but maintained an interest in fine art. Once he decided to fully embrace his artistic sensibility there was no turning back, and Krumrey has exhibited all over the world, even taking part in European Cultural Centre exhibition ‘Personal Structures’ during the 60th edition of la Biennale di Venezia in 2024.

Krumrey’s multi-faceted practice includes sculpture, painting, video and architectural forms that plumb the depths of human emotions and often possess a visceral sense of expression. He says that he works “in the quarry of human subsistence” and has “the heart of a poet” and influences of Baroque sculptor Bernini and Munch’s existential masterpiece ‘The Scream’ can be found in his work. He explores the inner consciousness, dreams, mythology and trauma through his art, and is a master at capturing body language. Krumrey creates Gesamtkunstwerks (total works of art) and is known for developing stages for his sculpture which act as “space installations” designed to stimulate all the senses through acoustics, light, temperature, smell, touch and physical sensation.

Culturalee spoke to Krumrey as he prepared for upcoming exhibition ITSLIQUID Body Language 2025, which will take place from 14th to 28th February at the Palazzo Albrizzi-Capello in Venice, and ‘Feldzug der Kunst’ in Soest, Germany in May alongside Klaus Stein, Martin Franke, Martin Hennig and Klaus Meyer-Oetzmann.

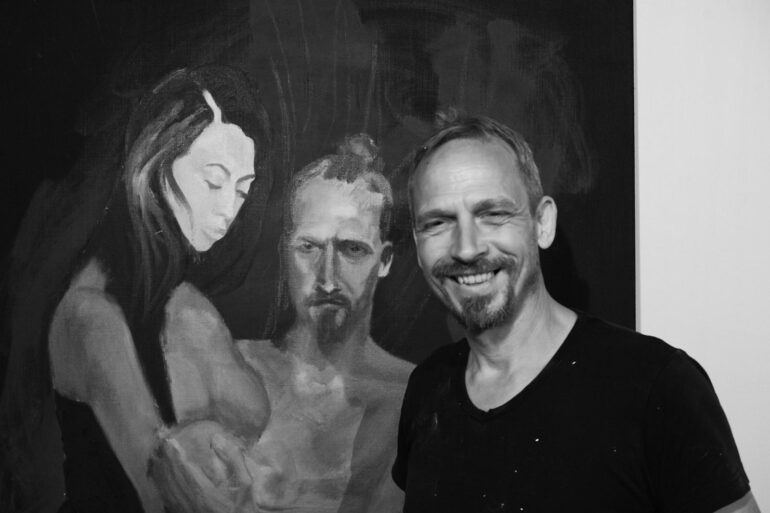

Photograph courtesy of the Artist.

Your sculptures possess an expressive quality that evokes the Baroque angst of Bernini, with references to classical antiquity and an existential aura that reflects the angst of contemporary times. What would you say are your biggest influences – are you inspired by specific sculptors from art history or by the anxiety of world events?

You interestingly name Bernini and Baroque in the very first sentence. I regarded myself always as a Italian Baroque artist, placed into our time and Bernini has got probably more subconscious means to me than I sensed when I first got aware of him in my twenties. But as a sculptor he wasn’t the first one inspiring my artistic feelings. I first fell in love at 13-14-15 with Michelangelo. But not so much with his most known works like David, Pietà or Moses but with those heavy reclining figures, especially Crepuscolo (Dusk) and Giorno (Day) and others like Brutus, the Slaves and late works like St. Mathew or Pietà Rondanini.

These all have one thing in common: they’re unfinished or partly unfinished. Nonfinito is the art historian term. And it didn’t bother me that it might have been accidentally due to the constant delay Michelangelo had in his commissions and the pressure from the side of his noble clients. I liked the roughness of the unfinished parts that added magic and a much greater variation of surface qualities to those works than the “finished” works ever had. But more than this, I got fascinated by the “stage of becoming” those unfinished works had: this never ending stage of development, a constant permutation, evolution, unfolding, a quality I personally perceived as being life’s most fundamental characteristic.

Especially the Pietà, Rondanini had an almost expressionistic contemporary appeal to me, as it shows how Michelangelo changed concept of the statue within the realization of the work – a thing sculptors almost never do when working in stone – and by the diminished thickness of the material he was forced forming tinier limbs and prolonged body forms that raise like a flame. The movement and expressive quality of this unfinished figure surely left an impact on me.

However, expressiveness, if you will understand this as movement of body posture, not only had its time in Baroque. Also, Hellenistic sculpture went from archaic to classic and to some sort of Hellenistic “Baroque” figuration from 300 BC onwards, if you think of the Barberini Faun here in Munich, the famous Laokoon group or one of the various tortured Marsyas figures. Never to forget the widespread and very much appreciated variants of grotesque figures throughout the whole antique to Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s grotesque heads in Classicism /late Baroque to the surrealist Nose and existentialist tiny or spindly figures of Alberto Giacometti. Deformation, physical torture or psychological torture – Angst – as you said, was and is always present in art. Simply, because we all are affected by it. We all know fear, horror, we perceive things or incidents that stir fear and so it is a theme in art. The world events of our present time, the mass killings in Gaza, executed by the descendants of former victims of the Holocaust or the war in Ukraine, all this is surely contemporary terror, a horror unbearable to perceive. Art must find ways in dealing with this, as it all happens within the field of collective consciousness. It affects us all, even though we want to ignore it. And an artist is sometimes just a seismograph, an indicator, a trembling pointer on a scale of human behaviour. So angst is definitely nothing an artist can ignore.

You’re quoted as saying “I work in the quarry of human subsistence and have the heart of a poet”. What did you mean by that?

Well, working in a quarry has always been the toughest job man could do and traditionally was organized by pressing slaves doing it. As I am forcing myself to dig deep into my very own soul and psyche for finding the ore of art I work in the quarry of subsistence, producing what is needed for staying alive as a human being and not just as a body. The precious raw materials I am searching for are insights into human nature, conditions of the soul. I therefore reveal myself to the public. As Bruce Naumann said: “The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truth”. I reckon finding truth in human existence is a deeply mystic doing, if you take a mystic as someone who attempts to be united with God. So it is indeed a revealing of mystic truth as we are all transcendental beings deeply searching finding contact with God within ourselves. And in finding those pathways between here, my everyday awareness and the true Self within myself and bringing this into awareness by art, is helping others finding those access lines easier within themselves, simply by the effect of resonance. Surely, that self-confrontational approach needs some bravery, so heart is a necessity and because I regard poetry as the mother of all art, the storyteller singing his observations in form of a hymn or a tale in verses at the fireplace is the prototype of an artist.

The ancient Greek word poíesis means just that: “creation“, so the Creator – God – is a poet. One of the most famous contemporary Greek musicians and singers (Alkinoos) is a dear friend of mine – like a brother – and he certainly is also a great poet in forming the texts of his songs. So poetry, music and visual art is just a different bandwidth, formally distinct, but very much the same on the scale of emotion, empathy and understanding of human condition.

You have a multi-disciplinary practice including painting, sculpture and video. What is your preferred medium?

My deepest love became sculpture, but I was 14 or 15 years old until I realized it. Nevertheless, I started from a very early age at 5 or 6 with drawing on my very own. No one ever told me to do so. I started copying birds, ornithologically correct from a biology book. I was never taught and no-one could believe it, seeing the results. My mom arranged one-on-one abstract painting classes after school and music lessons with a friend of Carl Orff in Dießen. Movies, film, dramaturgy became an issue very much later but got very intense at a certain point. At 27 I wanted to drop all the visual art and become a movie director. I wrote screenplays then and wrote my diploma thesis about film production. I worked a whole year on it.

You have introduced another dimension to your sculpture which involves creating a ‘stage’. Can you explain how you use these ‘space installations’ to explore the relationship between space and body?

I wouldn’t say I introduced another dimension. The third dimension is always present in sculpture. If a sculpture is set in an exhibition space or in a public space, a dialogue of the surrounding space and the artwork is unavoidable. The same happens to us, when we enter a space. If we go downstairs into a tiny brick loaded, vaulted jazz basement we do feel different than we feel, if we were entering a huge capitol like building with 22 m ceilings or if we pass through the portal into a gothic church with pillars like trees and mysteriously glowing windows. Every true architect knows this.

Every legendary nightclub exploits those principles. I just decided at one point that I would want to distinctly decide about the format of this dialogue and so I started designing purposely the space around the sculpture, the environment. Imagine this a bit like a theatre or an opera stage, where you have the lighting, the sound, the stage design and the actors. A snip with your fingers freezes the scene. Now you and the rest of the audience leave their seats, climb up the stage and enter the scene. In this moment everyone understands better what the protagonists truly feel, as everyone shares the same space, can walk in their shoes and see what they see and truly explore this for him- or herself. It is different sitting “in the audience” and “being on stage”. This is actually an idea Bernini first had, originally. He did implement the audience of his Baroque theatre productions onto the stage or was operating with secondary fake audiences so that the boundaries of perception of who was who got diffused. I just learned this from your questions about Bernini. Didn’t know myself. In this sense you are totally right: I introduced another dimension to my sculpture,

You have an artistic heritage with a Bauhaus connection via your Father who studied at hfg ulm with Albers and worked for Max Bill, and you were inspired at a young age when visiting the studio of Doris von Sengbusch-Eckardt, a sister of your grandmother. How has this creative bloodline appeared in your work?

Difficult to answer. I guess from my father I learned the terms consequence and truth. In the credo of Bauhaus every material is good i.e. correct, as long as its attributes, condition, appearance were in coherence with the intention and task of the design. Consequence in this case means, if you decided to use this or that material, you couldn’t make choices later-on that were contradictory to the material choice before. I will give you an example.

My father, while working for Deutsche Bundesbahn, shortly before retir, was auditing the design of the first generation of the ICE. The responsible design company (he knew them very well), was taking on a design of the ceiling of the train indicating some formal solutions deriving from wood construction (cranking beam like solution). The problem was: the ceiling was from fibre resin. No wood at all. Surely, technically speaking, no problem for realising a form that was reminiscent of a cranking beam construction in fibre resin. Yet he was raging: fibre resin as a modern industrial material was NOT AT ALL allowed for faking reminiscences of wooden structures. He blamed them being led by Anthroposophy instead of design etcetera. Either wood for wooden structures OR finding a formal language inherent within the physical condition of fibre resin. This ultra purity in material choices guides me until today no matter what I do create. Regarding my great aunt it’s less a formal approach I picked up from her, but the awareness of magic, emotion and deeply felt passion in every incident. In her world all had a soul. Her lizards, she was feeding every day, her plants and trees, the stones and materials she was working with. I took from her that the most important task for an artist was the fact that he or she was able to instil LIFE into his or her creations. If the artwork as an entity starts to live, the artwork is achieved. If not, it’s a failure.

Sculptor and Silversmith Professor Hartwig Ullrich was a mentor of yours in your twenties. How did his Bauhaus philosophies inform your work?

I learned a lot from him about the qualities of different materials that are playing a role in sculpture. How to use plaster or wax, how to work with copper, how to forge a spoon, a cup from a plane metal, how to treat silver when forging it, i.e. silver breaks like butter when it’s hot and many other things. I learned the difference between craft in stone masonry and artistic expression. One of the most important things I learned is to truly focus on the coherence of factual expression and intention of an artwork. He also taught me a lot of material purity and humility against the material used. Especially, to respect the formal boundaries of a block of stone. The formal closedness of a marble, for example, defines the boundaries of the artwork. If you wanted to create a figure with spread-out limbs, marble isn’t the material for it. Better use bronze instead. When using stone – apart from the technical difficulties – it always would imply to destroy three quarters of the stone and transform it into waste. So the closedness of form became a credo, not only because of respect towards the material, but also in terms of concentration: if you can tell the story in a closed form or as a torso, it’s always better than doing it in an outraging gesture.

Another thing he taught me, was of having a high awareness when using technical machinery like diamond cutting tools: the quickness of machinery like an angle grinder in taking away an originally highly resisting and hard material like stone leads very quickly into a carving style of “raping” the stone instead of respecting it. For him, the natural boundaries, volume and integrity of a stone needed to be respected more or less entirely. Surely all this led to conflict with the intention of creating truly figurative sculptures in stone. No matter of that, as I am perceiving every stone as an individual entity, I am deeply sharing his respect for the material in entirety.

After studying History of Art and switching to Economics, you gained an MBA and worked in marketing, advertising and venture capital but maintained an interest in fine art and artist studio. Many successful artists walked the line between art and advertising-notable examples including Warhol and Dali – what was the pivotal moment when you decided to devote yourself to the life of an artist?

I decided to become an artist when I was 15 while reading a legendary photo book of André Villiers about the life of Pablo Picasso I found on my dad’s shelf. At that time I already had some experience in painting, a bit in sculpture and had read every book about art in the library of my parents and seven metres bookshelf of art books in the school library. However, it was not a straight line of becoming an artist. The choice of entering business in my case was an artistic intention: I simply wanted to change society. So I went into finance. Later on I realized it was a dead-end. However, it taught me to trust in the primordial power of consciousness over reality instead of searching for the solution among the results of the creations of a misled consciousness.

Already this year you have been invited to exhibit in Group shows ‘ITSLIQUID’ in Venice in February and ‘Feldzug der Kunst’ in Soest, Germany in May alongside Klaus Stein, Martin Franke, Martin Hennig and Klaus Meyer-Oetzmann. You will be exhibiting two sculptures in ‘ITSLIQUID’ that you exhibited with the European Cultural Centre during the Biennale last year. What sort of impact on your career do these exhibitions have?

Exhibitions always have an impact on the career of an artist. Surely the Biennale of last year was a highlight in terms of reputation, but every exhibition is one step further ahead into the terrain where you want to arrive as an artist, in order to reach the audience you need to reach. Maybe these two smaller exhibitions achieve a better impact than the huge Biennale event where a single artist drowns in the sheer amount of artworks venues and visitors? At least I do hope to get a more direct response from ITSLIQUID ‘Body Language’ or ‘Feldzug der Kunst’ in Soest than I got from the mega event of the Biennale.

You are going to be featured in the Art Investment & Collectors’ Guide 2025: Most Investable and Prominent Artists, which will be published on 31st January. How does it feel to receive this accolade?

It surely goes down like milk and honey (blink). However I have no prejudice how it will turn out. Let’s see and hope for the best. Anything that helps a true artist moving and staying alive is a most welcome incident.

You’re currently living and working in Munich whilst building an artist’s studio in Italy. Is the imminent move to Italy inspired by its rich cultural heritage and artistic canon of world-class sculptors such as Michelangelo and Bernini?

Yes. I always felt like an Italian in Germany. I had a studio for 18 years in lower Bavaria near Passau and close to the river Inn, which was almost Austria; it didn’t feel like Germany whatsoever. Baroque grew alongside river Inn to Germany as the river once was the number one traveling route to and from Italy. Passau was good for creating art in a very focused manner. I then decided to move closer to potential audiences and moved the studio to Munich which was a failure. Just because Munich does not provide any suitable studio places for artists. There is just no empty spot, no left over or forgotten space, no loft artists could use.

Everything is exploited by real-estate moguls for pressing the highest rents in Germany out of the inhabitants of Munich. Just tiny, overpriced boxes for studio places given by political reasons fulfil an alibi patch of the city. So after three years of searching I decided at the end of 2016 moving to Athens, which was paradise, in comparison with Munich. Corona brought me back, as I had to take care of my dement mother. Unfortunately, I lost my studio in Athens because of these circumstances. After this I was looking where to move next. Italy was much closer than Greece, reachable by car and yes, I always felt familiar with Italian culture. History of art and modernity is not understood without the Italian Renaissance. I never felt i.e. Dürer, but felt close to Italian artists, even such problematic figures like Cellini.

Can you give a bit of insight into your creative process? What is the starting point for a new artwork – do you start with sketches or go straight to a 3 dimensional sculpture?

In sculpture I usually start sketching. Often just vague, probing, tiny drawings indicating axes, angles, directions, torsions and volumes. The greatest luxury is having a model at hand and directing poses or getting inspired from intuitive poses the model decides. It would be my ideal set-up of having at a certain time in the day one or more models present and ready for work, as Rodin did. As I usually don’t have, I use myself very often as a model, out of pure necessity. In the next step I also use video, when getting closer to a specific idea of a sculpture. As I am aiming into areas of sculpture where normal poses a model could physically hold, even for seconds, are impossible, video gives an edge in observing the unobservable. Very often the videotape provides evidence to movement and therefore muscular innervation that is counterintuitive. For example I am creating a work where – among some other aspects – I want to create the illusion of weightlessness of a body touching ground with one foot, as if it were the approach of a bird on the ground.

Taking a 360 degree slow motion video of myself jumping into the air with one foot several times reveals that the moment when the whole body APPEARS truly weightless is not the moment shortly before the foot touches the ground coming DOWN, but the split second before the foot leaves the floor on the UP cycle of the jump. This is just an example for resolving certain issues of a sculpture. There is more than this, as each sculpture is a complex universe of its own.

Any advice for young artists wanting to break into the art world?

If my mentors had told me this I would be in a different position right now. They sent me to other artists they themselves did admire, instead but weren’t suited for me. Only my classmate Robert, the only one also becoming an artist, sent me to the right professor. However, I didn’t listen to his advice back then and went my very own and complicated path. So, if you want to make it into the art world, look closely which professor seems compatible with your own artistic intentions. Whose artistic work do you truly admire and why? Does the professor seem to have a similar idea of art as you do or was at least a sense for your ideas to be expected? If you identify and shortlist some candidates like this, run a second check: is the prof as an artist himself or herself successful at the art market? Which galleries do represent your chosen professor? Are they good? Successful? If a professor passes these two criteria – fitting to your idea of art and being successful on the art market – go to consultation hour and talk to him or her. If they send you away, fix another consultation hour some weeks later. And so forth. Continue asking for improvement and return for consultation hours up to half a year until he or she loses nerves and gives you an application form. Bingo. You made it into the art world before you even started studying.