Curators of Dogtown: Preserving the World’s Largest Street Art Collection on Canvas

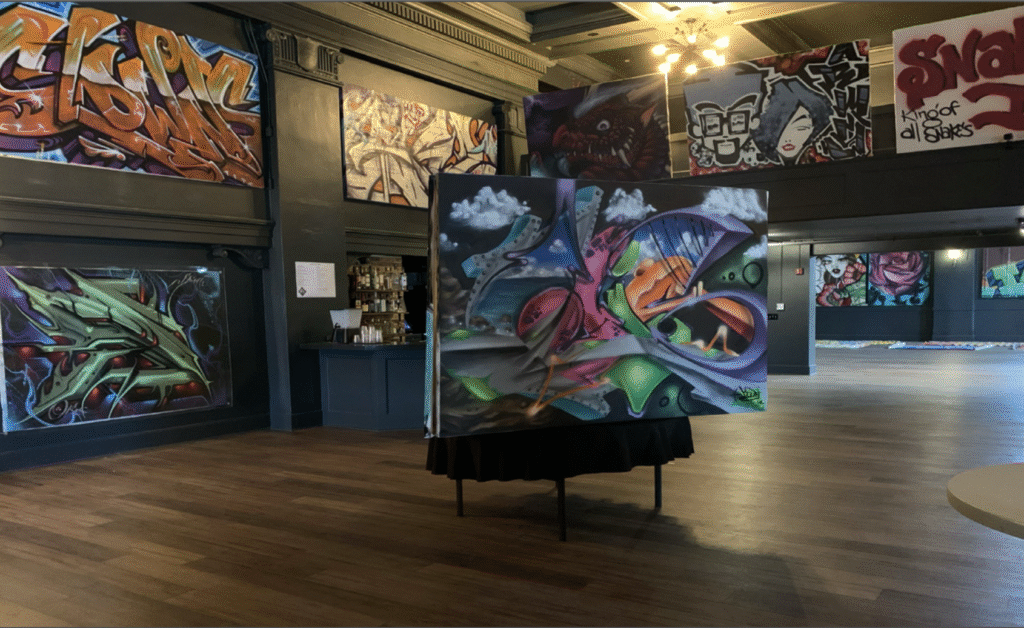

From the subways of New York to the freeways of Los Angeles, graffiti has long been the visual heartbeat of urban America, a story of resistance, creativity and cultural pride. The Dogtown Collection, curated by John Carswell and now co-led by his daughter Gloryanne “Baby G” Carswell, is the world’s largest graffiti and urban art collection on canvas. Spanning thousands of works and five decades of history, Dogtown celebrates the pioneers who transformed walls into museums of the people.

Together, John and Gloryanne are not only preserving graffiti’s legacy, they’re building bridges for future generations through AMGRAF, an arts institution that uses graffiti as a tool for education, empowerment, and community transformation.

Culturalee spoke to John and Gloryanne about Dogtown and its origins, legacy and family collaboration, cultural impact and preservation, graffiti as American Art and collaboration with at risk Youth.

John, you’ve described Dogtown as “the heartbeat of graffiti culture.” Can you share what first compelled you to start collecting works that were originally meant to live, and die, on the streets? How did that early sense of impermanence shape the way you preserve graffiti today?

That’s a great question. First I want to clarify that graffiti as an artform is much larger than any collection. It cannot be defined or legitimized by anyone, especially someone such as myself who couldn’t do what these artists do to save my life. What I could do, however, was historically preserve it and record the stories of artists that risked life, limb, and freedom to express themselves in a very unique way.

The purpose of the Dogtown Collection is to give future generations access to original artworks created by artists whose portfolios were long washed over and destroyed by having those artists record their most historic or critical pieces on canvases.

When I think of the “heartbeat”, I’m talking about the resuscitation of something that was gone forever. The ability for enthusiasts to study the style and nuances of the works created long after the art and artist are gone. From the first-generation pioneers to the LA muralists and every style and advancement in between the Dogtown Collection has tried to tell the American art story.

Gloryanne, you’ve stepped into your father’s vision as the next generation of curator at AMGRAF. How has this experience influenced your own perspective on graffiti, not just as art, but as activism and cultural heritage? What new directions or voices are you bringing into Dogtown’s story?

I was lucky enough to be raised around these artists, and while I didn’t know that I would work full time with this when I was young, these artists and the graffiti culture have shaped who I am as a woman. I met my best friend Miles through graffiti and we planned a life of adventures together which was cut short with his unexpected passing in August of 2021. I knew that nobody would fight for Miles’ legacy the way that I would. As we have continued losing friends, I’ve adopted those legacies into my work as well. My ultimate goal is to ensure these stories and artists are told not only through my life but continue for generations after I am gone.

The Dogtown Collection spans five decades and artists from Cornbread to the Under the Influence crew’s massive Prophets, Teachers & Kings mural. What does it mean to you to have this living archive serve as both an art collection and a historical record of graffiti’s global journey?

Graffiti wasn’t just an art movement. It was a phenomenon, a youth art movement that changed the world. What started 60 plus years ago by inner city youth searching for a voice and experimenting with the medium of aerosol paint sparked a global art expression crossing all economic, social and racial spectrums.

I chose to help tell the American story. The Dogtown Collection focused on the grime and grit within the genre more than the artist that went Mainstream. My criteria for collecting were finding the pioneers, style manipulators, guys that went all city or hit spots that defied explanations. Unlike any art form before, graffiti was built and sustained by phantoms, antiheroes and maybe even a few villains. There was never an intent to impress the public, these artists sought no admiration outside of their own peers. They seek only respect within their own culture. Society’s opinion has little to no value to these artists, which in my opinion makes it the purest art form to ever exist.

Graffiti has often been misunderstood or criminalized, yet Dogtown positions it as one of America’s most important cultural exports. How do you balance honoring graffiti’s rebellious roots with the responsibility of institutional preservation and exhibition?

Historically every art genre was misunderstood or critiqued in its infancy. Then as the art form developed and became popular it produced its own purists and traditionalists that could in turn hate the next genre. That’s the beauty of art. It’s never stationery. It always reflects a moment in time, societal condition or the soul of its creator. Graffiti is no different. It’s been despised, criminalized, misunderstood, accepted and beloved. All simultaneously. It just depends on who you ask.

It’s not my responsibility to defend graffiti as an art form. It would be arrogant for me to even believe I could. Graffiti, like every genre before it speaks for itself. My responsibility was to make sure it still existed in a physical form for generations to see and decide for themselves.

AMGRAF’s outreach programs bring graffiti legends together with at-risk teens to teach history, technique, and anti-gang values. What have been some of the most powerful transformations you’ve witnessed through these workshops, both for the youth and for the artists themselves?

That’s a tough one. Our museum, the American Urban Art and Graffiti Conservation Project (AMGRAF) realized there was an opportunity to use the art as a bridge between youth at risk and leaders within the graffiti community that had backgrounds that the kids could identify with. It is an interesting dynamic. Tough kids and hardened men find redemption together. They both need each other equally.

There are no psychological degrees here and these are not just “errant” kids. These are guys that have been down hard, in the streets and in the system. But these leaders speak a language these boys or gang members respect. They bring something to the table that no teacher, pastor or social worker ever could. These guys have been there, lived through it and are devoted to helping these kids heal, in fact they heal together.

The art is the catalyst, the goal is prevention but more often it’s walking a walk with these kids that no one else understands.The leaders within the AMGRAF programs have been down that path and have a unique ability to help these kids navigate it.

The “commission wall” projects, where rival youth gangs paint side-by-side under truce, are incredibly powerful. What challenges come with organizing these collaborations, and how do you measure success beyond the mural itself?

We are still developing this program as it’s a delicate balance. To date we have been mostly financial contributors. The theory is if young people in gangs can recognize the value in another young person’s life no matter where they are from, maybe there would be a hesitancy in inflicting violence on one another.

The production is a group project where everyone is invited and equally respected. No violence. A donated wall, food, music, paint and fun. The process takes young people from differing groups through introduction, light contact, and collaboration over the course of a weekend. A positive experience with someone that up until now they only speculated about. Then hopefully to understanding, camaraderie and maybe even trust.

We must help change the narrative. Fear and misunderstanding are killing these kids and we must continue to develop these programs. We may never know the full effectiveness of these programs. Gang violence will continue. But if only one kid at that crucial moment says, “Not that homie, he’s OK” and we break the cycle even once. Things will start to change, even if we never know.

Graffiti wasn’t just an art movement. It was a phenomenon, a youth art movement that changed the world. What started 60 plus years ago by inner city youth searching for a voice and experimenting with the medium of aerosol paint sparked a global art expression crossing all economic, social and racial spectrums. I chose to help tell the American story. The Dogtown Collection focused on the grime and grit within the genre more than the artist that went Mainstream.” Curator John Carswell

All images Courtesy of The Dogtown Collection.

Find more information on The Dogtown Collection here.

Find more information on AMGRAF here.