Michelle Alexander’s art doesn’t request comfort–it insists on confrontation. The Canadian-born, Chicago-based interdisciplinary artist brings a visceral clarity to themes often left unspoken: the tension between the body and societal expectation, the pressure of toxic beauty standards, and the psychic weight of conventional milestones like marriage. With a practice rooted in transforming the personal into the conceptual, Alexander draws from her own lived experiences—including a background in the fashion industry–to create materially rich works that push the viewer to reckon with the strange, beautiful, and often grotesque contradictions of femininity and selfhood.

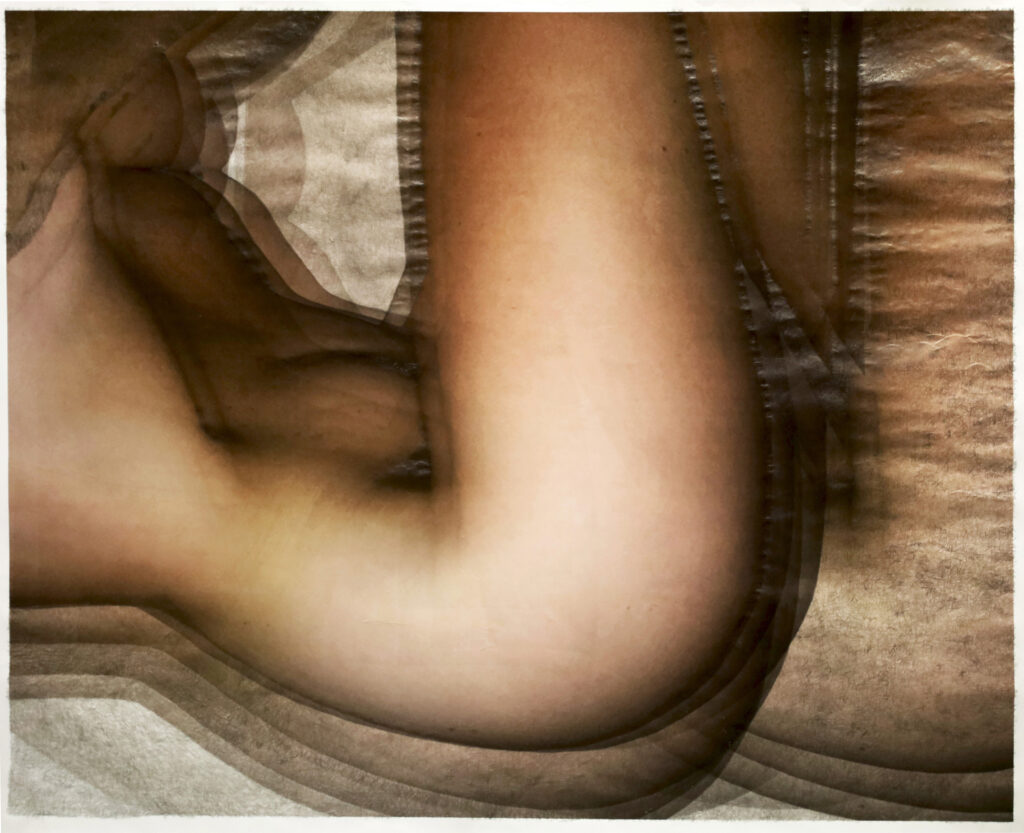

Whether she’s inviting audiences to literally walk over treadmill-like surfaces bearing images of her own body, crafting uncanny domestic objects from human hair and brushes, or presenting a wedding dress sewn with skin-like materials in a “monstrous” take on bridal imagery, Alexander’s work invites us to feel discomfort—not as an endpoint, but as a gateway to deeper understanding. Her recent curatorial project, Connective Thread at Ivory Gate Gallery in Chicago, further reflects her commitment to examining how bodies, identities, and materials intersect across contemporary art.

In this conversation with Culturalee, Alexander discusses her artistic evolution, the conceptual threads binding her work, and the ways she uses materiality to explore the often uncomfortable terrain of being seen, shaped, and categorized in today’s world.

Your work often turns discomfort into material expression. How do you begin translating something so internal into a physical, often confrontational form?

Discomfort is where everything starts for me. It’s a signal, sometimes in my body, sometimes emotional, sometimes just a weird weight I can’t explain. I don’t always start with an idea; it’s more of a feeling or a tension that lives somewhere under my skin. A lot of my ideas come from dreams, and I try to hold onto the sensation from those and build from there. I’ll start with an object or gesture that bothers me or makes me feel unsettled: something gendered, domestic, or too familiar. From there, I start pulling it closer to the body, turning it into a second skin, a wound, or a kind of armor. It’s not always direct, but it’s always personal and physical.

You’ve used everything from human hair to treadmills and skin-like materials in your work. What draws you to these unconventional materials, and how do they shape meaning?

I’m drawn to materials that already come loaded with implications. Hair, for example, feels so intimate and personal, you can hide behind it or throw it away like trash. Treadmills make me think of discipline, exhaustion, pressure and routines that trap us. Skin-like textures let me blur the line between the inside and the outside. These materials aren’t just tools, they’re part of the story. I want the work to feel like something you don’t just look at, but experience in your body. Something you feel before you figure out.

Having worked in fashion, how has that experience influenced how you think about beauty standards and the body in your art?

Fashion taught me a lot about how beauty gets shaped and enforced and how the idea of perfection is commodified. I saw firsthand how bodies are manipulated to fit into narrow ideals. This had a huge impact on me, especially as someone who already felt uncomfortable in my own skin. I use fashion-related forms like garments or accessories in my work, but not to beautify. I use them to question why we change ourselves to fit the world instead of the other way around. I think what’s left from all of this is a complicated relationship with my body, like it keeps letting me down. This frustration is the root of a lot of what I make.

Your wedding dress installation reimagines a cultural milestone through a monstrous, unsettling lens. What were you hoping to challenge or reveal with that piece?

The wedding dress is one of those objects that carries so much pressure. It’s supposed to represent the perfect moment, the perfect woman, the perfect life. But that’s never felt real to me, or maybe if I’m truly being honest, it has never felt like it would happen. I wanted to take that symbol and challenge it, make it raw, fleshy, altered, scary. I used elements from my mom’s and sister’s dresses, but I twisted them into something harder and more painful. It’s about trying to squeeze into this mold that I don’t think I fit into. It isn’t a fantasy. It is more like, what’s left of me when I try to be what others want?

There’s a strong sense of both intimacy and alienation in your work. How do you handle vulnerability—your own and the viewer’s—in your practice?

Vulnerability is where the work starts. I pull from my own discomfort, but I do it hoping someone else might recognize something in it, too. I’m not interested in tying things up neatly though. I want there to be tension, a little friction. Sometimes the work invites people in, sometimes it pushes them away. That mix is honest to me. We think we’re alone in our struggles, but when we open up, even just a little, it creates a space for someone else to step in.

In your curatorial project Connective Thread, how did your own perspective as an artist shape the way you selected or interpreted others’ work?

That show was a really personal extension of my practice. I started by reaching out to artists I admired and genuinely looked up to. I was honestly just a fan asking my favorites to be a part of something, and I was so moved that they said yes. After sharing the exhibition statement I had written, we began having rich conversations about womanhood and how it shows up in their work. I was drawn to artists who were thinking through the body and challenging preconceived notions of the female experience, not just representing it but using materials, asking questions, and transforming the subject into the object and back again. I wanted the show to feel like a shared nervous system, where each piece was in dialogue, not just with the others but with the viewer, too. The whole process was rooted in connection, vulnerability, and making space for each other’s perspectives.

Your treadmill installation—where viewers walk on fragmented images of your body—feels deeply personal. What reactions have surprised you most?

Funny enough, because of gallery safety rules, I was the only one who actually got to walk on the treadmill. But in my exhibition MY BODY / YOUR OBJECT, viewers were invited to walk on carpets printed with fragmented images of my body. Some people stepped on them without hesitation. Others paused, avoided them, or tiptoed around the edges. That contrast really stayed with me. It revealed so much about how people navigate boundaries, consent, and their own presence in a space. I want to make people aware of their body in relation to mine and to ask what it means to move through someone else’s experience or to see the body pictured and theirs and not mine.

But there’s something more personal I can’t shake. Watching people interact with the work made me realize how often I let myself be walked all over, not just literally, but emotionally. I’m a people pleaser to my core. Maybe, in some strange way, putting my body on the floor in this context was a way to reclaim some of that. To set a boundary by naming and confronting it head-on. Through the work, I’m trying to shift that dynamic to expose it but also to gain some agency over it.

Do you see your work as resistance to gender and beauty expectations—or more like a way of coming to terms with them?

It’s both. I don’t think those things are opposites. My work is a way to unpack the things I’ve been taught to believe, even if I don’t want to believe them anymore. I want to be seen but not objectified. I want softness but not to be dismissed. By staying in that uncomfortable middle space, I hope I’m challenging the systems that created it in the first place.

What role does humor or horror play in how you build your pieces—especially when working with discomfort or the uncanny?

Both humor and horror have a way of sneaking under people’s skin. They catch you off guard. I like when something makes you laugh and then you feel weird about laughing, or when you see something gross and realize it hits close to home. I often push familiar objects just far enough that they start to feel wrong: a dress that becomes a monster, a rug that becomes a moral dilemma. Those moments let me talk about hard things like trauma or pressure without making it too easy or too obvious.

As a Canadian-born artist working in Chicago, how do geography and cultural context shape your work?

I think it plays into my sense of disconnection from myself and my body. In Montreal, I feel really seen, sometimes uncomfortably so. In Chicago, there’s this weird mix of belonging and being invisible. It’s not about one place being better than the other, but about how my body is read and treated in each space. I carry that dissonance into my work. It shows up in the way I think about the body, as a projection screen, a shield, a shell. I think my work lives in the in-between.

Find out more about Michelle Alexander here.