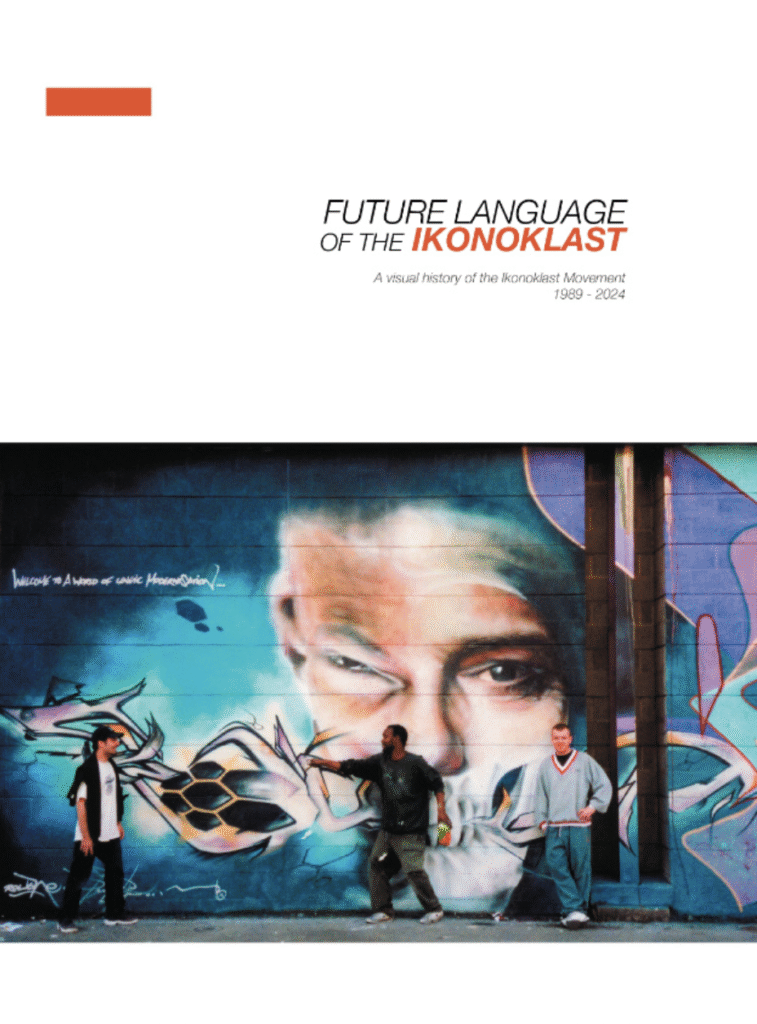

Remi Rough-acclaimed artist, author and founding member of graffiti crew The Ikonoklasts–has authored a new book that explores the legacy of the Ikonoklast Movement. Future Language of the Ikonoklast (Velocity Press) will be published in July and documents the history of one of the most semimal countercultural artist movements of the 1990s. The Ikonoklasts–formed in 1989 by Juice 126 with Remi Rough, Part2, Stormboy, System, Tee Roc and Solo1–became known as the ‘post graffiti super group’. At the heart of The Ikonoklast Movement was a collective attempt to change the graffiti art landscape through collaboration and artistic exploration.

The Ikonoklasts were inspired by Style Wars, Subway Art and Spray Can Art to push the boundaries set by graffiti rules of the “NYC Graffiti Motherland”, and they set out to explore their own artistic aspirations within the UK and hone their distinctive anarchic identity. The “spiritual painting home” of The Ikonoklasts was the Blueprint Gallery in Birmingham, run by Juice 126 and Europe’s first outdoor painting space.

Rough maps out the impact of the Ikonoklasts on graffiti art across the UK and Europe with his richly illustrated book, and captures for posterity the 35-year legacy of the movement, with a focus on their most prolific output of the 1990s. The Tate’s Simon Armstrong comments:“The Ikonoklasts are pivotal to the British-European interpretation of graffiti writing and the evolution of the artform.”

Culturalee caught up with Remi Rough to get some insights into the new book and talk about his experiences as a founding member of The Ikonoklasts.

What inspired you to put this book together now, more than three decades after Ikonoklast first formed?

It felt like the right time and this story had been left out of some key exhibitions that really it should have been noted within so I felt it was the right time to share it. We did an exhibition last year with most of the Ikonoklast members but I had already been working on the book before that happened. I also have to thank the artist Kid Acne for harassing me to do it.

What does the title The Future Language of Ikonoklast signify to you, and how does it reflect the ethos of the movement?

The title of the book was actually coined early on by Keith Hopewell (Part 2), during the initial stages of gathering imagery and talking through the concept with the rest of the group. There were plenty of titles in circulation, but the exhibition at Fleet Studios—Future Language of the Ikonoklast—stood out. That show featured artists beyond our core collective, and the title seemed to speak to something bigger: a sense that what we were part of didn’t belong solely to us. It hinted at a language others could pick up and carry forward. In many ways, it captured the spirit of the book—something ahead of its time, the full weight of which only revealed itself decades later.

How did the collective initially come together, and what drew each member to this shared vision of redefining graffiti?

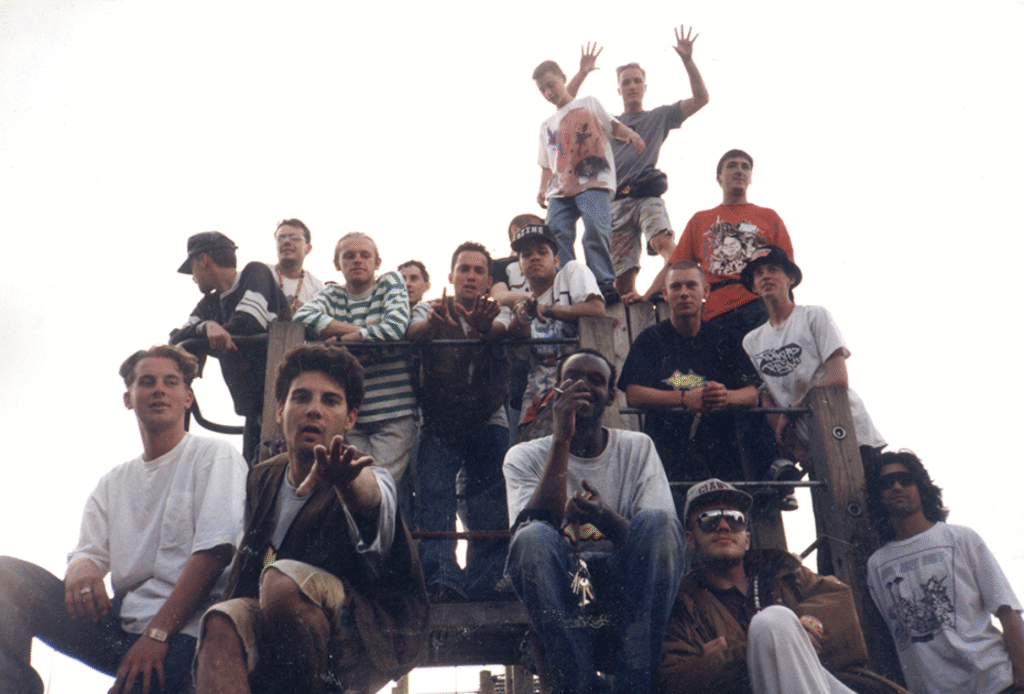

Juice 126 had a vision—a collective of like-minded artists who could push the graffiti movement beyond its established boundaries, embracing experimentation and forward-thinking ideas. At the time, there were key events dotted around the UK—Bustin’ Loose in York, the World Graffiti Championships in Bridlington, and Class of ’89 in Worcester. Word would spread, and artists would appear from all over the country—sometimes even further afield. That’s where we first crossed paths with artists like JonOne, Vulcan, and Lokiss. At several of these events, you’d notice small groups breaking off, gravitating toward one another—drawn together by shared intent. Juice was often the one holding those complex, necessary conversations about how we could evolve. After about three of these gatherings, he called a more focused meeting in Birmingham, which would become the first official Ikonoklast assembly. Present were Stormie (Stormie Mills), Keith Hopewell (Part 2), Solo One, System, Juice 126, Tee Roc, and myself. From that point on, we didn’t hesitate—Selly Oak Park in Birmingham, where Juice worked as a youth worker, became our creative base. Selly Oak was renamed The Blueprint Gallery—it was our home away from home. It is mad how we managed to continue the meeting up and connectivity considering this was before the internet and mobile phones but we did with letters and phone calls from land lines.

Ikonoklast set out to break away from the traditional graffiti styles rooted in New York. What were the key aesthetic or philosophical ideas driving that shift?

The manifesto was unapologetically clear: it was about the art—not the vandalism, not the history. That had all been thoroughly documented by then. For us, the focus was on pushing the boundaries of spray paint as a medium, exploring how far it could stretch, and where it might lead when combined with other forms of art-making. Collaboration was at the heart of it—not just the typical set-up of one artist doing letters and another a character, but something more ambitious, more conceptual. We began creating wall pieces that operated as unified visual ideas—something rarely seen at the time. Each artist brought a distinct aesthetic, and that diversity became a strength. We learned from one another, shared techniques, and kept evolving. Juice, for example, taught us how to mix spray paint to create colours—vibrant pinks, purples, anything we imagined—on a scale few others were even attempting. As our work developed, it started drawing attention beyond the UK, and invitations followed—from France, Germany, Italy… it began to spread.

How do you see Ikonoklast’s influence reflected in today’s urban art scene—both in the UK and internationally?

I think the fact that artists today can paint whatever they want, freely and without hassle, speaks volumes about the groundwork we laid. Take the wave of large-scale, photorealistic portraits on buildings now—many of those painters might not know the name Ikonoklast Movement, but they’re walking a path that Part 2 and System carved out. That’s just the truth. Jim Prigoff—the late photographer who co-authored Spraycan Art for Thames & Hudson—travelled to the UK in ’91 and ’92 specifically to document Part 2’s work. He’d seen photos in the States and felt compelled to see it firsthand. That work was meant for a follow-up to Spraycan Art that never came to be, but the influence remains undeniable. Both Part 2 and System shaped the visual language of spray-painted photorealism—their technique and precision became a benchmark. And yet, there was a rawness in their work, a kind of energy, that no one’s quite been able to replicate. You also have to credit Stormboy—what he was doing with portraiture intertwined with abstraction was ahead of its time. And Juice was taking graffiti-based abstraction into entirely new territory. The only real contemporaries working at that level were artists like JonOne and Futura 2000.

In what ways do you think the group succeeded—or even failed—in its original mission to push graffiti beyond its perceived boundaries?

It absolutely succeeded—if not just in the art, then in the friendships that have lasted over 35 years, and the memories and projects that will outlive all of us. Back then, the success was tangible: we were being invited to paint in cities across Europe and even as far as Australia. The challenges came later—trying to sustain both the relationships and the level of work as life began to take its course. We were growing up while all this was happening—starting families, building homes—life, inevitably, got in the way. But I don’t believe it ever failed. We weren’t built to accept failure. We were tough, adaptable kids who knew how to move through changing circumstances.

And as we matured, so did the work—each of us evolving in our own direction. I, for example, returned to a more left-field approach to letterform, breaking it down into something like a new visual language—which is where I find myself now. Stormie’s work has become beautifully melancholic, his figurative paintings echoing memories, friendships, and a life that once was. Part 2 has moved beyond photorealism into a layered, gestural language all his own. Is that failure? I don’t see it that way. We might all have different takes, but the fact that I was able to create this book—and that a publisher like Velocity Press believed in it—is, to me, a quiet and lasting testament that what we built truly meant something.

Can you talk about how collaboration worked within Ikonoklast? Were there creative tensions, and how did those shape the work?

There were never any creative tensions among us—we all truly loved the process. Typically, the night before, we’d spend hours drawing or discussing ideas for the piece. We rarely arrived with a fixed plan. Sometimes, one artist would have an idea, and we’d all find a way to build on it together. It was always about the final wall—the end result—something graffiti itself often struggled with, as egos often took centre stage. The only real tensions came when it was time to photograph the work; each of us had a different vision for how it should be captured. But honestly, there were so few arguments or fallouts in those early days. We were comfortable around each other, thoughtful, and really in tune with one another. We all shaped the work, every small detail added something, often we would critique each other’s work as it was happening with a view to hopefully making it even better.

I also have to mention the parents, many of whom were incredibly supportive. Solo’s mother was always so kind, taking care of us when we visited Hinckley. System’s parents did the same, and my own parents treated everyone like family—feeding, housing, and looking after us as if we were their own, which, in many ways, we were.

What was the process of curating the visual material like—were there lost pieces, rediscovered works, or surprises along the way?

It is hard to overstate just how powerful the archive process was. Between System and me, we somehow managed to hold on to nearly everything. Over decades, photos, negatives, sketches, flyers, and other fragments of our journey were preserved. It is an extraordinary archive that now feels almost impossible in retrospect. Only one or two pieces have truly been lost to time. Everything else was still there, waiting to be rediscovered.

Curating the visual material for the book became an emotional excavation. We were not just sifting through old artwork; we were stepping back into rooms filled with conversation, energy, and intention. Forgotten gems surfaced. Some pieces I had completely forgotten existed. Others I had never seen before, like two remarkable paintings by Juice that quite literally stopped me in my tracks. There were also candid photographs of friends and collaborators that I had never come across before, offering glimpses into moments that might have otherwise faded from memory. I spent a small fortune on redeveloping old negatives, and Juice, System, and I dedicated countless hours to scanning, sorting, and reflecting. The process was deeply nostalgic, but more than that, it was grounding. It reminded us of who we were, what we built, and how far we have come. I truly hope people feel some of that when they look through these pages. Not just the history, but the heart behind it. The writing helps tell that story in a powerful way as well. Lois Oliver’s main text is extraordinary. It captures not just the timeline or the facts, but the spirit of the movement and the individuals within it. Every contributor brought something personal and honest to the table. The overarching narrative is simple and profound. A group of young men, driven by the desire to become artists, supporting each other in pursuit of that shared goal. Decades later, we are still doing exactly that. And that continuity is, in itself, a kind of success that is difficult to quantify.

One of the most meaningful rediscoveries for me was the first mural Juice 126 and I painted together in London, just weeks after we met at Bridlington in 1989. I had not seen that wall since the day we finished it. To find it again, and now be able to share it, felt like closing a perfect loop. Another unforgettable moment was uncovering a photograph of Futura and Juice mid-conversation, surrounded by the unfolding creativity of the Contents Under Pressure exhibition in London during the mid-1990s. These images, and the many others we have included, tell a story that has rarely been shown. Almost all of them have never been published before. They do not just document the work. They document a time, a culture, and a community that helped shape what street art would eventually become. To be able to put that into the world now, in such a considered and lasting way, feels incredibly special.

Looking back, how has your personal artistic journey been shaped by your time with Ikonoklast?

I honestly don’t think I’d be the person or the artist I am today without the Ikonoklast Movement. It gave me a real sense of family, purpose, and a steady stream of inspiration. It let me be myself and follow the creative paths that felt right to me, even if they were a bit out there. Being a young graffiti artist in the 90s wasn’t always easy, but Ikonoklast accepted me completely. Any wild idea I came up with was met with support, not judgement.

Painting alongside Juice for so many years had a massive impact on me too. Our styles are really different, but something just clicked. It became this instinctive, natural thing. We’ve made some of our best work together and kept advising each other all the way through our careers.

What I really hope is that this book helps bring some well-deserved attention to the lesser-known artists from the Ikonoklast crew. Every single one of them is a legend in their own right. They deserve to be seen, heard, and remembered.

If you could give advice to younger graffiti artists who are looking to break conventions, what would it be?

Know your history, both the traditional and the underground. Juice introduced us to so many artists we might never have discovered on our own, and that knowledge shaped us. Master your craft, but stay humble, and always share what you learn. If we keep it all to ourselves, this movement cannot grow or survive. And finally, always be an iconoclast.

FUTURE LANGUAGE OF THE IKONOKLAST: A Visual History of Ikonoklast Movement by Remi Rough is published on 18 July by Velocity Press priced at £29.00. The book is available to purchase with a limited edition dust jacket and A2 poster. exclusively available via Velocity Press. The special edition is priced at £34.00.

All images courtesy of Remi Rough/ Future Language of the Iconoklast.