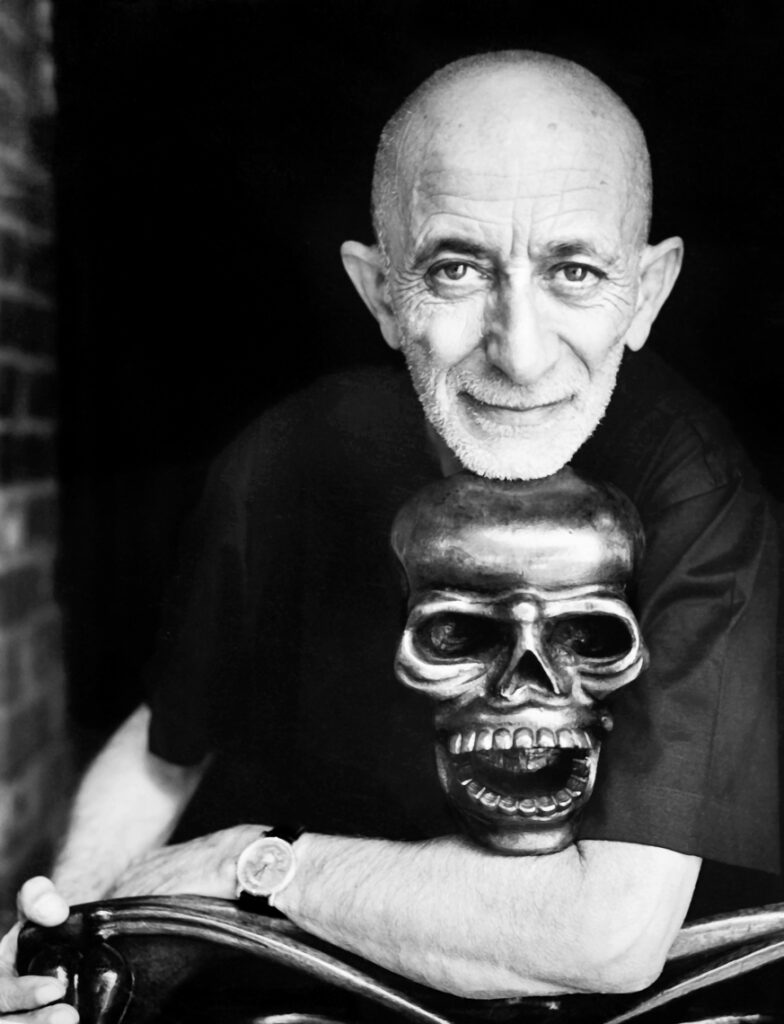

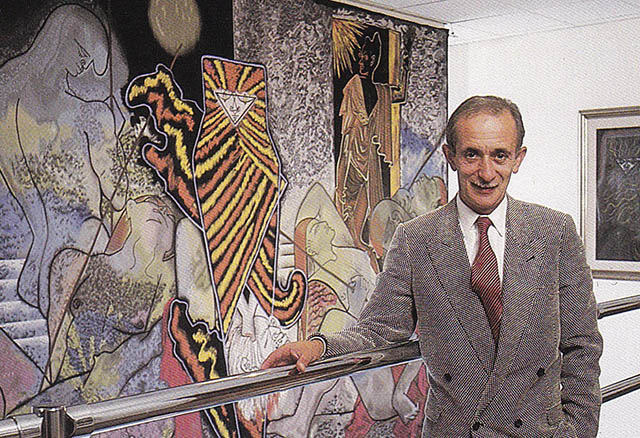

Chloë Cassens comes from an interesting dynasty: she is the granddaughter of Gucci Timepieces founder Severin Wunderman, representative of the world’s largest collection of Jean Cocteau artworks. Wunderman redefined the Gucci brand’s timepieces as the “Time Lord” and during his lifetime he amassed a world-class collection of artworks by French artist, film director, poet, playwright and novelist Jean Cocteau.

Chloe Cassens inherited the creative gene and created ‘Sacred Monster’, an intriguing project which examines Cocteau’s lasting and surprising influences on contemporary culture. Cassens gave a talk in Venice earlier this year about Cocteau and her grandfather’s collection at the Peggy Guggenheim museum, where a major Cocteau exhibition was mounted to coincide with La Biennale di Venezia.

Culturalee spoke to Chloe Cassens about continuing her grandfather’s mission to create a historically significant Jean Cocteau archive and her artistic project ‘Sacred Monster’.

Your grandfather was Gucci Timepieces founder Severin Wunderman. Were you very close to him as a child, and how has his creativity and obsession for Jean Cocteau influenced you and your career?

I was very close to my grandfather in his lifetime. I adored him. It was his creativity and obsession for Cocteau which has influenced my career and me directly – I grew up with Cocteau’s work literally surrounding us, totally immersed in it. I was a kid, so I took it for granted. When my grandfather passed away in 2008, I found myself digging deeper into Jean Cocteau and his work as a way to process my grief. A lot of my current work is still an extension and an expression of that grief.

You represent the Severin Wunderman Collection, which is the largest collection of Jean Cocteau artworks in the world, and makes up the Jean Cocteau Museum collection Severin Wunderman in Menton, France. Was this a legacy that you wanted to take on since childhood, and does it feel like a big responsibility to take on this collection at such a young age?

When I was a kid, my grandfather would give me tours of his art collection, but it was always a fun thing we did together. He never really presented it as this big, important thing, it was almost like he was sharing his favorite toys with me and explaining what they were. I think he saw that I was academically minded even then, but that was the majority of it. I didn’t think much about the responsibility or what it meant then. Nowadays, it’s a totally different story. Not a moment goes by where I am not totally aware of what an enormous responsibility I have taken on, thankfully with the support of my family.

‘Sacred Monster’ is an intriguing title for a project. The name is derived from Jean Cocteau’s play ‘Les Monstres sacrés’, which was presented at the Théâtre des Ambassadeurs in Paris in 1966, with costumes by Yves Saint Laurent. What is it about the play that inspired you to create an ongoing project about it?

To be honest, I wasn’t thinking specifically about the play itself when choosing a title, but rather what the term meant then and what it means now. A Sacred Monster is a cultural figure or celebrity whose eccentricities–or negative qualities–are overlooked due to the transcendence of their creative output. Back in Cocteau’s day, I think it meant overlooking the fact that someone like Sarah Bernhardt was once a sex worker, had one leg, or was Jewish (she was a French national treasure at a time where Jews in France were particularly reviled). Today, I think it’s evolved to reflect our attitudes around ‘cancel culture’–that most of the people who have made undeniable contributions to arts and culture are more than likely not good people. An example I like to give is Kanye West, who I just published a piece about.

You recently hosted a Q&A and film screening of The Blood of a Poet (1932) at the Philosophical Research Society in Los Angeles. What attracts you to this film, and what issues were raised during the Q&A?

I love The Blood of a Poet for many reasons, but one of them is the fact that it is a really special snapshot of Parisian nightlife in the 1930s. The cast is made of icons who would go on to make impacts in totally different spaces: Lee Miller, Jean Desbordes, Féral Benga, and Barbette all have scenes in the film. I always love bringing Cocteau’s work to a receptive audience, and the one at PRS was extremely engaged and plugged-in. They asked all sorts of interesting and thoughtful questions–one person asked what weapon Cocteau would use in a street fight–but my favorite was when someone asked me for my phone number.

Oil on canvas, 97 x 129 cm, Private Collection © Adagp/Comité Cocteau, Paris, by SIAE 2024.

How does it compare culturally and creatively living between Los Angeles and Paris, and do you think the American sensibility gets the philosophical and existential nature of Jean Cocteau and his legacy?

I’m very lucky to live between Los Angeles and Paris–they’re two totally different cities, and I feel a little bit like I live a double life. My life in Los Angeles is quiet, more solitary; I spend a lot of my time there in nature, in my rose garden or with my horse. In Paris, I am out all day every day, socializing almost every night, surrounded by incredible man-made beauty in the form of its arts and architecture. I don’t know that I could live full-time in one city, as culturally and creatively I need their balance. Unfortunately, it does mean that almost all of my relationships–familial, platonic, romantic–are long distance. I have an internal world clock in my body that always knows what time it is in Paris or Los Angeles, so I can know what hour it is for my loved ones on either side.

I think that in some ways, American attitudes are more equipped to handle Cocteau and his legacy – if only they knew about him! There is a fluidity and freedom in the American spirit that I do not see in France, or Europe, all that much. Americans are way more open minded to the idea of someone who worked in all types of creative mediums, who didn’t pigeonhole himself to just one thing.

You’ve hosted podcasts, written and produced short films, made a name for yourself as a DJ and radio host, and are currently writing a book about your grandfather’s life and legacy, as well as being the gatekeeper and preserver of his Cocteau collection through the museum in France. Do you feel that all these skills and experiences influence each other in some way?

Yes, I do. Remember the film Slumdog Millionaire? The main character knew the answers to all sorts of random trivia questions, based on the varied and wild experiences he’d had in his life. I feel a little bit like that, in my own strange way. My skills and experiences have sharpened me into a bizarre sort of one-woman Swiss army knife.