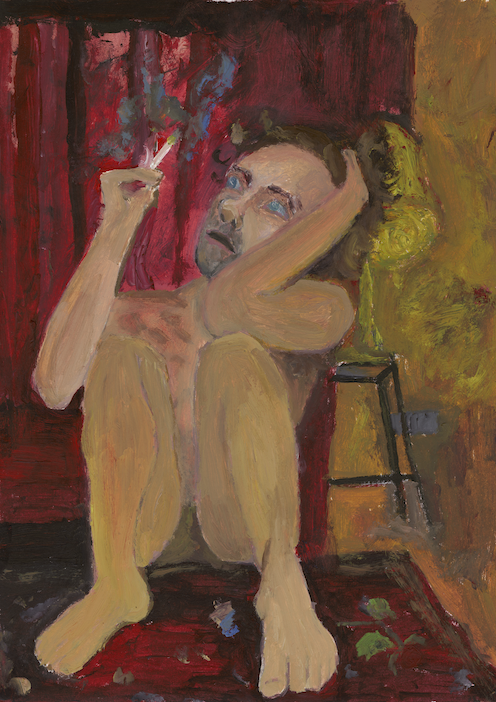

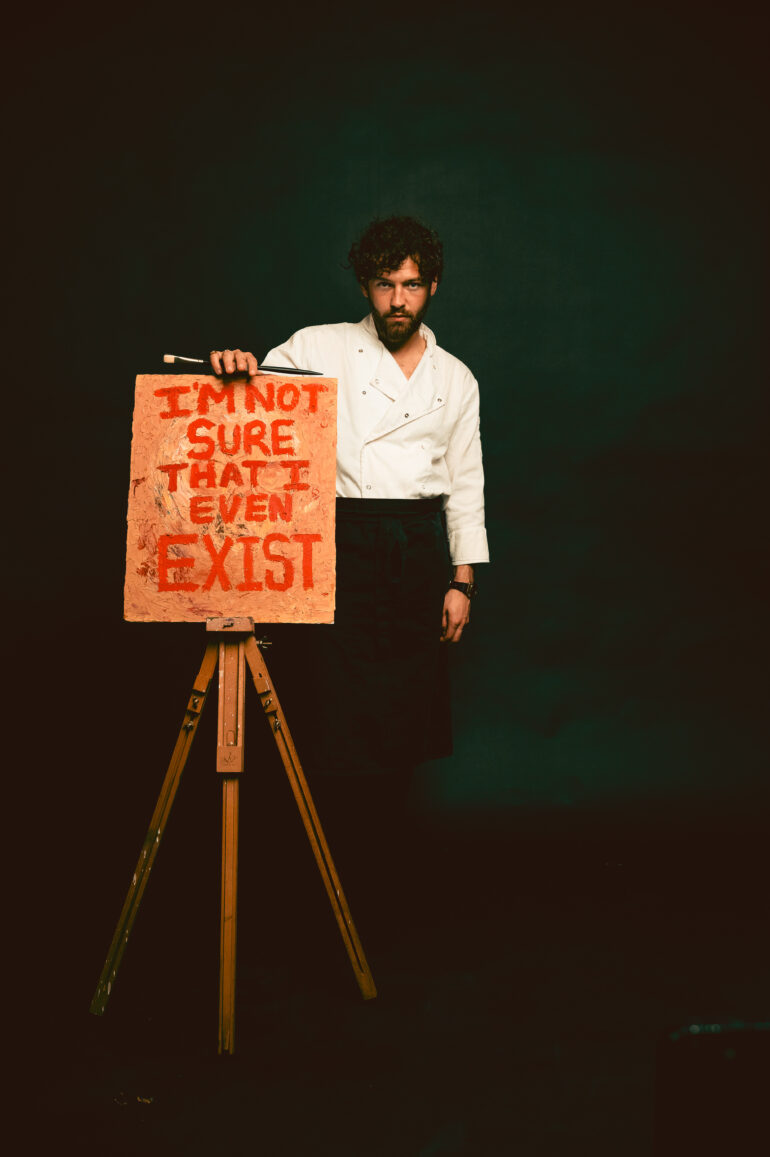

Restaurateur turned artist Daniel Farrow presents a new solo exhibition of paintings at Bantof in London that offer a candid look at addiction, recovery and sobriety. Farrow’s solo exhibition will run from 2nd June until 2nd September, 2025 and features a series of new paintings that channel his experiences of the restaurant industry, struggles with addiction, mental health and recovery.

Farrow’s new paintings are a departure from his earlier work years ago which was created in altered states during a turbulent phase of his life as a restaurateur. Since selling his restaurant and discovering sobriety, Farrow’s painting style has developed to reflect his sober life and taken a more abstract turn. Culturalee spoke to Farrow as he prepared for his solo show in London’s Soho district.

Can you tell us about the inspiration behind this latest body of work that you’re exhibiting at Bantof in London? What led you to explore addiction, sobriety, and the restaurant industry through painting?

Reflections from the Restaurant has been manifested over a two year period of healing and self discovery. When I left my restaurant two years ago, I’d just given up drugs and alcohol, the fabric of my own reality had unwoven, torn apart stitch by stitch. Everything I thought about myself, the good and the bad, was called into question. I was in a state of open vulnerability, truly broken with absolutely no idea of where to go or how I would get there, how I would escape the mess I found myself in. Art had provided a guiding light. The works back then were painted on many occasions by an inner child that needed to be seen, to be loved and to be given space to play. It is only now, after all this time, that I feel truly healed from a history that was frankly plagued with grief. I have overcome the scars left behind by an abusive childhood, homelessness, addiction and so called ‘failures’. This exhibition is kind of the final chapter of the journey, a full stop on the final sentence that is that story, and I’m already focused on the next chapter, a lighter one, filled with humour and appreciation for all that is good about this wonderful life on this peculiar rock that we live on.

There’s a motion to the creation of my works; I get swept up in them. In this instance, I notice that impulsively I have used deep crimson reds and a vast array of blues, dictating the mood that my period in my restaurant often reflected. Hospitality is hot and passionate, it can be relentless and unforgiving. At times it is also blue, frankly a personification of mood that was all too familiar back then. Drugs, sex, alcohol, promiscuity and mania—all ingredients for the cocktail ‘a perfect storm’ in hospitality. It’s all there, within the work.

When I was a child I spent a great deal of time hiding away in my room. I would paint another world, a reality so different to the one I was experiencing. In my teens, I made sculptures and sold them online for beer money. By the time I’d left foster care, I’d given up on painting. It wasn’t until I broke down during my time at the restaurant that I picked up a brush again through intuition. I’m self-taught but somehow it doesn’t feel like it’s a skill that I’ve learned, the work just sort of comes out of me, from somewhere subconscious. The learning happens when I look at each finished piece and am able to reflect on where it came from.

Many of your works feel deeply personal—how do you balance vulnerability with artistic expression?

I suppose I don’t really think about it. So far it’s been like each piece has been painted by someone different, a version of me from the past. A part of oneself that needed to be seen but wasn’t. These works are conversations I have with my past selves. I don’t feel vulnerable any more in creating; really I’ve been set free by the art and continue to express freely.

In creating this body of work, I’ve spent a long time reflecting on what was arguably the most chaotic and challenging chapter of my life. There’s one piece called ‘The Fire and the Flood’ that I spent many days sweating over, tweaking, scratching away at paint with my finger nails. One evening, I took a garden rake to it and set it on fire and actually to me it’s just the perfect piece, it speaks of everything I went through a few years back, including a fire…and a flood.

I try to steer away from influences in my work. To be honest, I’m actually terrified of it. To look at the beauty of someone else’s expression and try to make it my own, I just can’t do it. I won’t. It’s kind of a rule that I’ve set myself that allows me to be present when exploring art. The influence really comes from my own life and interpretation of the world.

At first it was the addiction that created the work. When I talk about versions of past selves painting, I think about pieces from my last collection like ‘Cocaine Clown’ that was created after consuming five grams of cocaine. Now, I am painting with more clarity. After this body of work, I can already see a monumental shift in direction, more light, less shadow. It’s symbolic of the healing that has taken place.

Did painting play a role in your healing process or in coming to terms with your past?

Yes, it’s profoundly and singularly responsible for not just my healing but my survival. Art, in no uncertain terms, saved my life. In the beginning, when I started painting, I was in so much pain. I don’t feel any of that now, only empathy towards my younger self. If I could transform my art works into a living, breathing therapist, that’s be wonderful!

The restaurant world is often glamorized but can be incredibly tough behind the scenes—how do you aim to challenge or reveal those realities in your work?

I have no fear in ‘literally’ painting a picture of what it can be like. I was on 24/7, from the heat of the kitchen to cocaine benders, waking up next to nameless strangers, only to be thrown out of bed and straight back into the kitchen or front of house in a world of pain, then repeat. I mean, at the time it was very glamorous, but in the same way an old Scorsese movie is glamorous: I revelled in the booze, the parties rife with cocaine and nudity, breaking open bottles of champagne whilst dancing on top of the bar. God, I did have some fun, but only to fall from such great heights to suspected heart attacks, hallucinations, depressions that felt like being skinned alive. I remain enamored with the fact that I survived that period, but I still love hospitality, I still do it, I just know how to navigate that landscape now

Can you describe your creative process? Do your pieces start with a memory, a visual, a feeling—or something else entirely?

Often a memory or a feeling. I think sometimes that’s quite apparent in the work. In this series ‘Blue Chef’ is a feeling, ‘The Fire and the Flood’ is both. My first exhibition was filled with pieces that were from the subconscious climbing out of their tomb. In this series, it’s a reflection of thoughts and feelings, a reaction. Going forward I’m very focused on beauty not just aesthetic.

How do you choose your materials and palette, especially when dealing with such emotionally charged subject matter?

It’s so impulsive. I kind of wish it were a choice sometimes, but it’s much more a compulsion. When I look back at a finished work, some of the choices make so much sense to me but I almost can’t even take credit for it, it all just happens and then I’m left standing there looking at a painting, like, ‘Wow, that just came out of me’.

Has your approach to painting changed since leaving the restaurant industry?

It’s significantly more conscientious and self-reflective. I have so much more clarity on who I am as an individual now and the fluidity or ever-changing nature of the self. I’m much more in tune with my humanity. I’ve sunken into an incredibly comfortable place, and I’m at home in myself now and I feel that’s going to profoundly change the direction my art goes in going forward.

I hope with this exhibition, as with the last one, people find room for empathy in their lives. Empathy for themselves as much as for others. You know, it was incredible to watch so many grown men cry at my last show. It’s like the work had opened a door that people could step through to reflect on their own grief and found space to let a bit of that go, in empathy.

Do you see your future practice continuing to explore autobiographical themes, or are there other directions you’re curious to explore?

I do. However, I have probably more than 40 unseen works that are like notes in a diary, bookmarks of ideas for future collections. I know that my next exhibition will be themed around why we give the gift of flowers. It’s going to be titled ‘Why do we gift flowers in the knowledge they will inevitably die’. It poses the question to the audience, and it’s an opportunity for me to learn from others and to appreciate and interpret beautiful things. After that I’d like to explore symbols through time, the idea of who we are and where we come from on a more universal level. I think I’ll travel and document that one on film too.

How do you envision your role as both an artist and a storyteller in today’s cultural landscape?

I’d never really thought about it as a role, only I suppose in the sense that on embarking on my artistic journey I had stepped into the role of guardian to the inner child, a version of self that needed help and guidance through non judgement and setting a path for healing. Perhaps some of my works may provide others a moment of reflection and the space for retrospection. That would be nice, though I don’t see it as something to take upon myself, I’m just a man learning about the world and my place in it.