Ukrainian artist Natalia Millman spoke to Culturalee as she prepared for her upcoming solo exhibition Letters to Forever: A Visual Art Installation Turning Stories of Grief into Community Healing, at St Peter’s Church, St Albans, Hertfordshire from 6th util 28th August, 2025.

The exhibition is supported using public funding by Arts Council England in partnership with Cruse. Letters to Forever is a deeply personal exhibition born out of the artist’s experience of losing a loved one to dementia, and features 200 letters documenting experiences of loss and grief offered by members of the public. The multi-media exhibition is supported by the Arts Council, and Milman also collaborated with Cruse Bereavement, a charity for which she is an ambassador.

Your exhibition “Letters to Forever” 2025 will take place at St Peter’s Church in St Albans this August. Was there a specific reason for choosing a Church as the venue? I wondered if the choice of location reflects the spiritual nature of the exhibition?

The choice of St Peter’s Church for Letters to Forever is deeply intentional. Churches hold a unique kind of silence — not empty, but full. Full of memory, longing, hope, and energy. I wanted a space that could carry the weight of absence, and the beauty of presence, all at once. This is where life’s biggest moments often unfold — births, marriages, deaths.

When I enter the church, I subconsciously anticipate the stillness — the lingering sense of something greater than myself. My heart rate slows, the walls shield me from the noise of the outside world, and I’m naturally drawn inward and slow down. Letters to Forever is about connection: to those we’ve lost, what we have lost and love that stretches beyond time. The church is not just a backdrop — it becomes the vessel for my work.

There’s something deeply powerful in inviting people into a sacred space and asking them to bring their own offerings of memory. The spiritual nature of the venue amplifies the emotional honesty I hope the exhibition evokes. It’s a place where the invisible feels almost tangible — and that is exactly what Letters to Forever is about.

“Letters to Forever” will be an immersive exhibition addressing grief and loss by featuring 200 public letters on loss. How did you gather together the letters, and how will you present them?

The idea for Letters to Forever emerged following the death of my father in 2019. The experience of personal loss was overwhelming and unfamiliar—my sense of identity and reality was shifting. I was searching for connection, trying to understand the neurological and emotional changes involved in updating my internal “system” to no longer include the “we” that had once existed. I struggled to speak openly about it, but discovered that art and writing became essential tools for navigating, untangling my complex emotions.

In the early stages, I reached out to grief-related and creative platforms with an open call. Over the past three years, I have received more than 200 letters from around the world, a few in different languages. Ranging from a single sentence to several pages, these submissions took many forms—words, poetry, sketches—and each author was encouraged to express themselves freely. I invited contributors to sit with their grief, to feel its rise and fall connecting their mind, body, and soul—and then to write. For many, this became a cathartic process, a way to consciously embrace their grief.

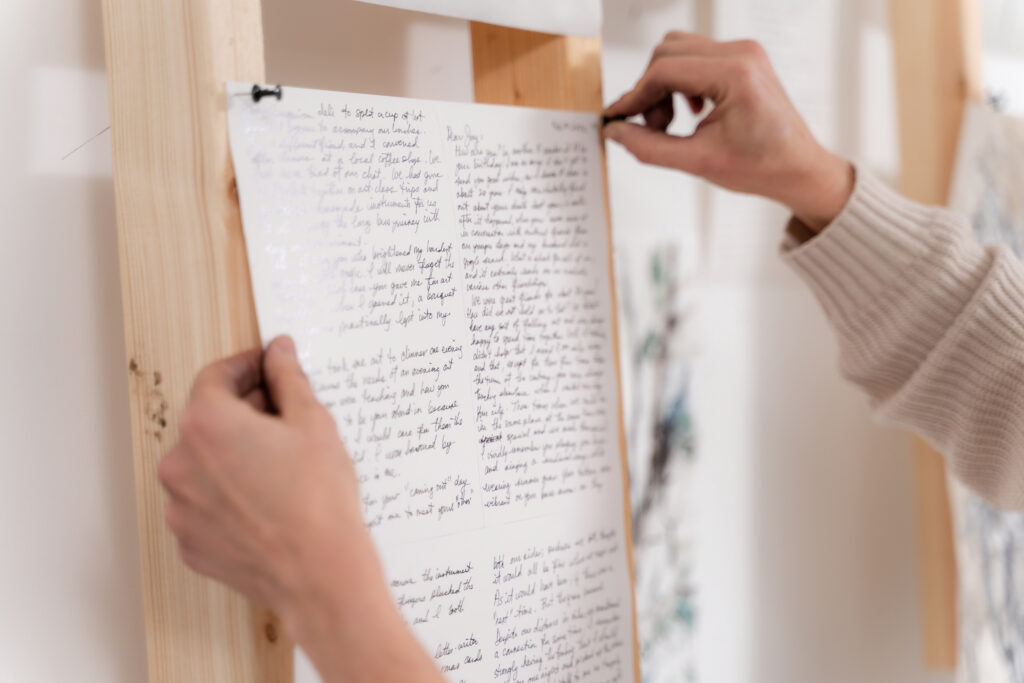

These letters form the emotional core of Letters to Forever. In response to each one, I created a drawing using ephemeral tools such as feathers and sticks, often working intuitively—with my eyes closed or while listening to a recording of the letter—pushing oil stick across the surface in response to the emotional tone. These 200 drawings are presented within a central structure shaped as a cube, wrapped in translucent voile that gently filters light, creating a sanctuary-like atmosphere for reflection and remembrance.

The exhibition extends beyond visual art, with text from the letters transformed into immersive sound works: A Meditation on Loss guides visitors to map grief within their bodies and visually express this experience; A Sound Bath uses healing frequencies to help release emotional blockages; and Letters into Sound translates each phoneme into a tone, creating a sonic composition that gives voice to the letters in a wholly new form.

Sculptural pieces include a suspended printed textile featuring the most frequently used words from the letters—derived through narrative analysis—a hand-knitted artwork made from paper spun original texts, and a specially commissioned scent blending therapeutic oils that both explore the depths of grief and offer comfort.

An art book, resting on a church table, holds the full collection of letters alongside my selected drawings. A video work, incorporating my own performance, runs parallel to selected sentences drawn from each letter, visually weaving their words into a shared narrative.

The installation spills beyond the church interior into the surrounding grounds. Visitors encounter an intimate ring of pre-loved chairs and a path scattered with engraved plaques, featuring selected phrases from the letters, nestled among existing gravestones, inviting quiet contemplation.

A live performance element further animates the project, created in collaboration with multimedia artist Casey Francis. Combining video, sound, projection, and my live readings of selected letters, the performance brings the deeply personal into shared space—intimate, ephemeral, and alive.

At its foundation, Letters to Forever is a communal project. Five community workshops, led by local art and grief practitioners with a focus on companions of people with dementia and the Ukrainian community, offer a space for storytelling, reflection, and collaborative creative expression. These workshops extend the project’s reach—transforming it into a living, participatory memorial, and a celebration of our shared human capacity to carry loss with tenderness and resilience.

“Letters to Forever” is supported by Arts Council England. How important was it to have the Arts Council’s support in order to get this project off the ground?

The support from Arts Council England was absolutely vital in bringing Letters to Forever to life. This project began as something deeply personal, but I always knew it needed to evolve into a shared, communal space—one that could hold many voices and honour diverse experiences of grief. The backing of the Arts Council not only made the practical side possible but also offered a sense of legitimacy and trust that opened doors.

It enabled me to collaborate with Cruse Bereavement, whose expertise helped ensure the project created a safe and supportive environment. It also allowed me to work alongside other artists, sound designers, and grief practitioners, and to realise the project on a scale that truly honoured the emotional depth of the letters I had received.

Most importantly, this support meant I could create something genuinely accessible and inclusive—reaching wider audiences, fostering meaningful community engagement, and offering others a space to connect with their own experiences of loss through art.

Your 2021 exhibition ‘Vanishing Point’ at the Crypt Gallery in London featured a collection of work exploring the space between life and death through a collection of work you produced after losing your father, including photography, sculpture, video and installation. Was the production of the exhibition a cathartic process for you, and can you explain how this project led to the ‘Grief Letter’?

Vanishing Point was my first attempt to process the enormity of losing my father through art. I poured myself into that exhibition—it was raw, instinctive, and urgent. I was assembling broken found objects, “repairing” them, extending their life. The collection emerged into the exhibition organically. It was cathartic—though at the time, I was doing it without fully realising or understanding why. I simply needed to do it. Looking back now, I can see it was an unconscious way to begin repairing myself, to hold myself through something I didn’t yet have the language for.

Alongside this, I was always interested in community engagement—speaking with people, hearing what they think, and inviting them to participate in the process. I believe, we are storytelling creatures; it is how we make sense of our world and connect with one another. I wanted to hear their stories of grief—who or what they were grieving. Perhaps their letters would speak of deep relationships, of love, joy, connection, or of the wounds left behind. I was curious, not just about their loss, but about the lives held within it and the opportunity for light and growth amidst grief.

That’s when I started writing to my father. At first, it was private—just a quiet release of what I couldn’t say out loud. But gradually, I began to wonder what might happen if others had that same space. That was the beginning of the Grief Letter—an open call that invited people to sit with their own loss and express it however they needed to. Those early letters became the emotional foundation for Letters to Forever.

Initially, I called this project Grief Letter, because that’s exactly what it was—clear, direct, and honest. But as the project evolved, I changed the title to Letters to Forever. The word forever carries a certain ambiguity—it holds both the permanence of loss and the enduring nature of love and memory. Because human beings are finite, how can we understand forever? It felt more expansive, more open to interpretation. Grief is never one thing—it shifts, lingers, resurfaces—and forever speaks to that ongoing presence. Letters remained in the title as a clear anchor, a reminder that at the heart of this project are real voices that want to be heard, real stories, and the deeply personal act of writing as a way of reaching out—into memory, into connection, and into something beyond ourselves.

You have said that your biggest inspiration is nature, your biggest fear is memory loss and your biggest hope is harmony. How do you reflect nature and examine memory loss in your artwork?

Nature has always been my greatest inspiration—not just visually, but energetically. There’s a kind of quiet wisdom in the way nature works: its cycles of decay and renewal, the resilience of trees, the softness of earth, the way everything is connected beneath the surface. I see my own grief, fear, and hope reflected in those patterns. With ageing, we gravitate towards the earth and eventually are absorbed by it. My work is a dialogue with those natural rhythms—it helps me understand the world and my place in it challenging my own fear of mortality.

Memory loss, on the other hand, is my other deepest fear. The idea of moments, people, entire lifetimes slowly fading away is something I’ve both witnessed and felt. Seeing my father’s transformation into someone new and going back to innocence, was a painful life experience. I lacked knowledge about dementia unaware of how stigmatised it is, especially in Ukraine. In my practice, I explore this fragility of memory through broken, layered, and ephemeral materials—fragments that feel like echoes of something that once was. I used intentionally fragile materials—pieces that were never meant to last, much like memories slipping through our grasp. It was also my way of beginning a conversation around memory loss, which I continue through my work with Arts for Dementia.

My process is intuitive and tactile—collecting, burning, mending, layering. I work with natural and found materials, not just for their textures, but because they carry stories. Hands, roots, stones, paper—they all hold something ancient, something universal. I use them to explore time, memory, and what gets left behind. Trees often appear in my work as I see them as people, who unlike us, are quietly observing the world in salience. They are symbols of endurance and interconnectedness—mirroring human resilience, even in the face of grief or memory loss.

As well as exploring feelings of loss and looking into the void between life and death through your art, your practice also draws on your Ukrainian heritage and the painful experience of the war in Ukraine. Does creating art provide a safe space and a space for exploring personal loss as well as a sanctuary for people suffering with dementia or caring for loved ones with dementia?

Yes, absolutely—art has always been a sanctuary for me, a space where I can hold complex emotions, explore the unknown, and find grounding when life feels fragmented or uncertain. It allows me to step into the space between life and death with more awareness and less fear, to sit with grief in all its rawness and nuance. Over time, I’ve come to understand that this sanctuary isn’t only for me—it’s something I can offer to others through my practice.

My Ukrainian heritage is an integral part of my identity and creative voice. Although I left Ukraine over twenty years ago, the war has reawakened something deep in me. Each piece of tragic news trembles through my roots. The grief of displacement, cultural loss, and generational trauma echoes through my work and intensifies the more personal experiences of loss I’ve explored. Art becomes a way of holding both—personal sorrow and collective memory—honouring not just pain, but the extraordinary resilience of the Ukrainian people.

That same sense of refuge carries into my work with people living with dementia. In my monthly workshops in St Albans, I see how the creative process can reconnect participants to themselves and to each other, even when language begins to fade. I invite them to explore mark-making, natural materials, or memory-based themes, and gently encourage them to describe their work or share how they feel. The feedback is always heartening—people feel calmer, more present, and often uplifted.

I believe, that art works where language falls short. It engages the senses—sound, touch, scent, image—and allows for abstraction, metaphor, and intuition. This is the foundation of Letters to Forever. The project incorporates these sensory layers to create an immersive experience that invites people to connect with grief not just intellectually, but somatically and emotionally. It is especially important for those whose voices are often unheard.

As part of Letters to Forever, I’m running a dedicated workshop for carers of people with dementia—individuals who are so often overlooked, yet live with a constant, quiet grief. They experience what’s known as anticipatory grief: caring for someone who is still present, yet changed. Time and space can feel disjointed for them, and their own needs often fall away. This workshop offers them space to pause, reflect, and be creatively held in their experience—to express without words, to reconnect with themselves.

In a world that often rushes past grief, illness, change and uncertainty, art creates a sacred space. It allows us to slow down, to feel, to remember, and ultimately, to connect. That is where healing begins.

You’re an ambassador for ‘Arts for Dementia’ and you run monthly creative workshops for people with dementia in St Albans. Do you use the arts as a form of therapy for the people attending your classes, and have you noticed that art and creativity can offer some temporary respite from the condition?

Yes I do see art as a powerful form of therapy—not in a clinical sense, but as a deeply human practice that allows people to connect, express, and simply be. In my monthly workshops in St Albans, the focus is on in-the-moment experiences. There’s no pressure, no expectation, no need for skill—just the invitation to be present.

By listening closely and observing gently, we begin to understand more about dementia—not just as a condition, but as a lived experience. People with dementia often communicate in ways that are non-verbal, intuitive, and rooted in the senses. That’s why I use tactile materials—sand, bark, flowers, tree branches, natural textures that stimulate memory, sensation, and emotion. Through these sensory experiences, participants can fully engage—emotionally and cognitively—without needing to rely on words. Very often people surprise themselves at what they are able to create.

I think, art creates a neutral ground. It removes hierarchy and allows everyone in the room to connect as equals. It’s a space where people are not defined by their diagnosis, but by their presence, their creativity, their humanity. And that, in itself, offers respite—not just from the condition, but from the isolation that can often come with it.

As an ambassador for Arts for Dementia, I’m committed to promoting their vital work in supporting people living with dementia and their companions through a social prescribing model. I also advocate for the valuable training they provide to creatives and organisations striving to make their engagement programmes inclusive.

I encourage anyone who is curious, in need of support, or simply wants to be part of this vital work to explore what Arts for Dementia offers. Whether you’re a carer, an artist, or someone looking to make a difference, their resources and programmes are incredibly valuable.

Did you study art or are you self-taught?

I’m a self-taught artist, and creativity runs in my family. I’ve always been drawn to art, even as a child, but it wasn’t until about eight years ago that I began taking weekly art classes and started to explore it more seriously. From there, I joined an emerging artist mentoring platform Studio Fridays, which helped me grow and refine my practice. Now, I work from my home studio, where I continue to develop my work independently.

I was offered a place on the MA Fine Art course at Central Saint Martins, which was a huge honour, but due to family circumstances at the time, I had to turn it down. I dedicate a lot of time to self-development and self-study—both on a personal level and in terms of my artistic practice. I’m constantly learning, researching, experimenting with new materials and approaches, and deepening my understanding of the emotional and conceptual layers of my work. I am guided by curiosity, intuition, and a deep belief that the creative journey doesn’t have to follow a traditional route.

What is the starting point for each project, or does each exhibition evolve naturally to the next stage?

For me, every project begins with a feeling of something unresolved, something stirring beneath the surface. There isn’t always a clear plan; it’s more like following a thread of emotion or experience and seeing where it leads. In many ways, each exhibition grows out of the last, almost like chapters in the same story. And at the heart of it all is loss.

Loss is such a vast, layered theme—it’s not only about death. It’s about change, transition, the loss of identity, of homeland, of mental clarity, even the quiet losses within motherhood. It touches everything. My work sits in that space of bittersweetness—where grief and beauty coexist, where fragility and strength live side by side.

So yes, while each project may begin in its own way, they’re all part of a continuous exploration. They evolve naturally, intuitively, and often unexpectedly—like life itself.

Letters to Forever, A Visual Art Installation Turning Stories of Grief into Community Healing is at St Peter’s Church, St Albans, Hertfordshire from 6th util 28th August, 2025. The exhibition is supported using public funding by Arts Council England in partnership with Cruse. For more information go to Natalia Millman’s website: www.nataliamillmanart.com

All images courtesy of Natalia Millman.