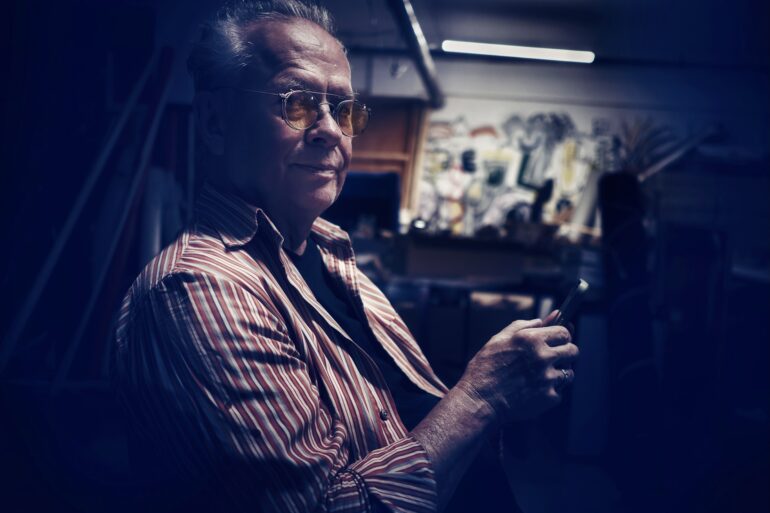

At Culturalee, we’re drawn to artists who challenge how we see, feel, and understand the world. Robert Mack is one such visionary. A multidisciplinary artist working across fine art photography, filmmaking, painting, and video installations, Mack’s work has been exhibited in major institutions including the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Reiss-Engelhorn Museum in Mannheim, Germany, both of which hold his art in their permanent collections. His ongoing Wrapped Series — where he drapes subjects in sheer material and photographs them in the ethereal light of the Southern Californian desert — blurs the line between photography and painting, intimacy and transcendence. From socially charged documentary work to haunting explorations of anxiety and emotion, Mack’s practice invites us to reconsider beauty, vulnerability, and the human condition.

Raised as an “air force brat,” the son of a decorated WWII veteran and painter, Robert Mack grew up across sixteen homes in twenty years, from Japan to Germany. This nomadic upbringing shaped his instinct to document and explore human experience, a thread that runs through his wide-ranging practice.

Mack’s work is defined by its haunting intensity — from Wrapped, his ongoing series where sheer fabric transforms the human form in desert light, to Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity, a rare study inside a U.S. maximum-security hospital for the criminally insane. His Anxiety Series paintings further probe disorientation and collapse in response to today’s cultural and environmental uncertainties.

A multidisciplinary artist working in photography, filmmaking, painting, and installation, Mack has exhibited widely in the U.S. and Europe, with major institutions like the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Reiss-Engelhorn Museum in Mannheim including his work in their permanent collections. Whether in socially charged documentary projects or ethereal explorations of beauty and transcendence, Mack compels us to look again — and look deeper.

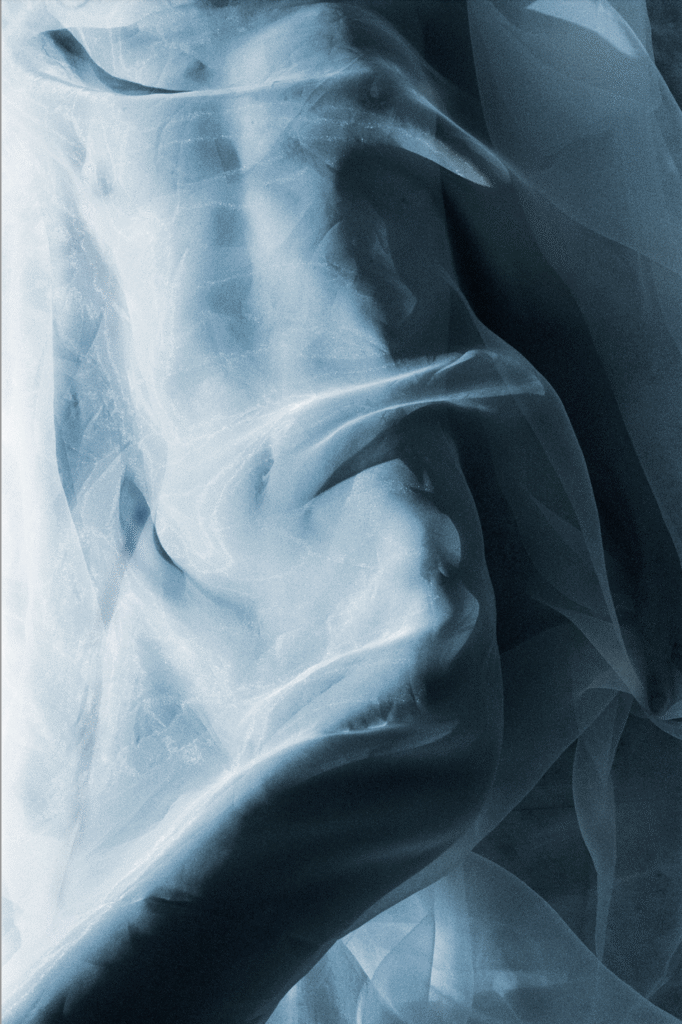

Your Wrapped Series has become a defining body of work for you, exploring themes of dreams, beauty, and transcendence. What first inspired you to begin wrapping your subjects in sheer material, and how has the project evolved since those early images on your bed?

Taking photographic portraits has always been a passion of mine. Initially, I was taking portraits of friends at my apartment. Then one day I saw a photo by my friend Sally Mann of her son lying on his back with sheer material covering his entire body. The sheer material was stuck on his bloody forehead where he had just received stitches from an injury.

I began to cover my subjects with sheer organza material and discovered so many new possibilities and themes available to me which launched the Wrapped Series which is still ongoing today.

Unlike many contemporary photographers, you avoid digital manipulation and even cropping your images. Why is that purity of process so important to your vision, and what does it allow your work to reveal that digital effects might obscure?

I often take several photographs of the subject, but find that the first image I instinctively take, with the exact framing selected, is often the best image. I have no problem with photographers using digital effects to create an image to their liking, but for me capturing the image as it is in that actual moment of reality is the most challenging approach, and if the photograph is good or great, then the most satisfying.

Much of your work is created in the quiet expanse of the Southern Californian Hi-Desert at sunrise. What role does the desert’s light and atmosphere play in shaping the mood and depth of your images?

The Wrapped Series continued in the Joshua Tree high-desert in California where I found that the pure desert light before and during sunrise provided images of such creative clarity. Since I began the process in the early morning, the subjects were still, in a sense, in a dream state and as the light changed so did their emotional state. As I mentioned, I would use sheer material over their body and would swirl the material almost like a painter, creating images that looked more like paintings than photographs.The magical everchanging desert light would highlight and reinforce this creative approach.

Your earlier collaboration with Grace Zaccardi, photographing patients at a maximum-security facility for the criminally insane, remains a powerful example of art as social commentary. Looking back, how did that project influence your later explorations of vulnerability, humanity, and emotion in art?

I approached the criminally insane photography with a clear intention of trying to take images without judging the individual, even though half of these men were dangerous to themselves or others and many had committed murder during their psychotic episodes.

Since this approach produced images of such intensity, humanity and eventual acclaim, I continued throughout the years approaching subjects with the same intention of respecting their vulnerability, not pre-judging the individual, and allowing whatever emotion presented be acceptable.

You move fluidly between different mediums — photography, filmmaking, painting, and video installations. How do these disciplines inform and enrich each other in your practice?

Photography became my primary interest as a young developing artist, where I enjoyed learning and accomplishing the various aspects required of photography while at university, such as technical, composition, understanding color, film mediums available, and choice of subject.

At university, I was also allowed to create my own curriculum which included filmmaking, art history, and painting. As you can see from my three primary bodies of work—fine art photography, filmmaking and painting—each medium contributed different skills as I moved from medium to medium. Portrait photography was a collaboration between the subject and myself. Filmmaking as a producer and director was a collaboration between many individuals. And finally my recent oil painting series combines all I had learned from working in these different mediums over the years.

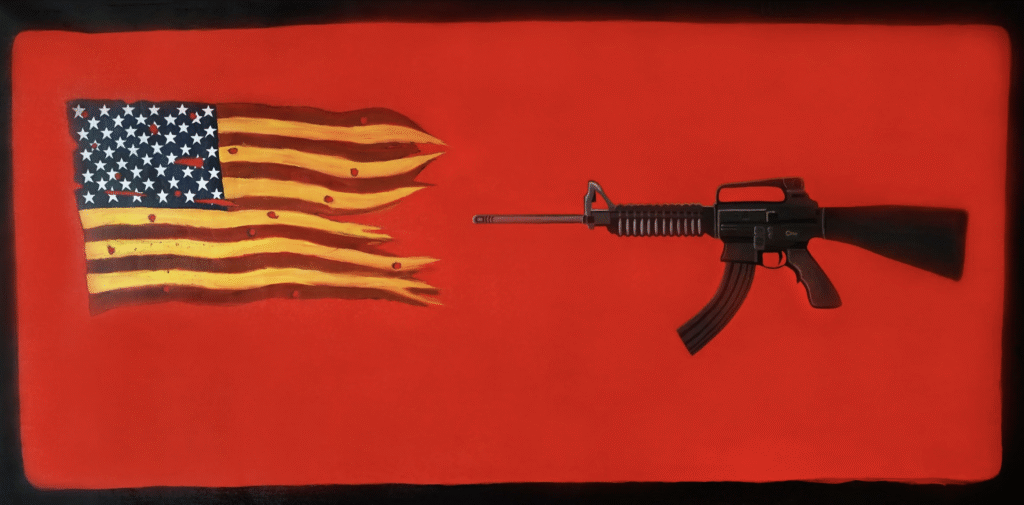

The Anxiety Series paintings you created — disembodied faces suspended in elaborate forms of hair — capture a deep sense of unease and disorientation. What personal or cultural experiences fueled that series, and what conversations do you hope it sparks?

The Anxiety Series oil paintings began when the Covid pandemic forced most of us to shelter in place for long periods of time. My father Matthew Mack, a wonderful plein air painter, had passed away and left me all of his art supplies, so it felt right for me to begin to paint. The resulting floating head paintings hovering over solid endless backgrounds only confirmed the anxiety we all were feeling. As I continued painting, monstrous creatures began to appear. Then the canvases got larger and larger, up to 4 by 8 feet and some even became political. Such as an AR-15 assault rifle shooting holes through the American flag and three beautiful glaciers that are on fire.

I hope these paintings allow the viewer to feel and process the anxiety of this difficult period we all are experiencing. They might provide an individual reflection on his or her own anxious feelings, stimulate dialogue with others, perhaps even motivate one to take action towards the positive. None of the above was my intention as I was painting, for I just painted what I felt as these daily world-wide crazy events unfolded.

Your work often feels suspended between reality and dream — raw yet ethereal. When viewers encounter your art, what do you hope they take with them emotionally or spiritually after standing in front of one of your pieces?

When viewers encounter my art, I hope they experience a space for reflection, imagination and meaning in a chaotic world. Emotionally, I hope they carry away a sense of introspection, an invitation to linger with their own inner landscapes.Spiritually, I wish for them to feel a sense of wonder at the beauty that exists in spite of all we experience.

For more information on Robert Mack visit: https://www.robertmack.com