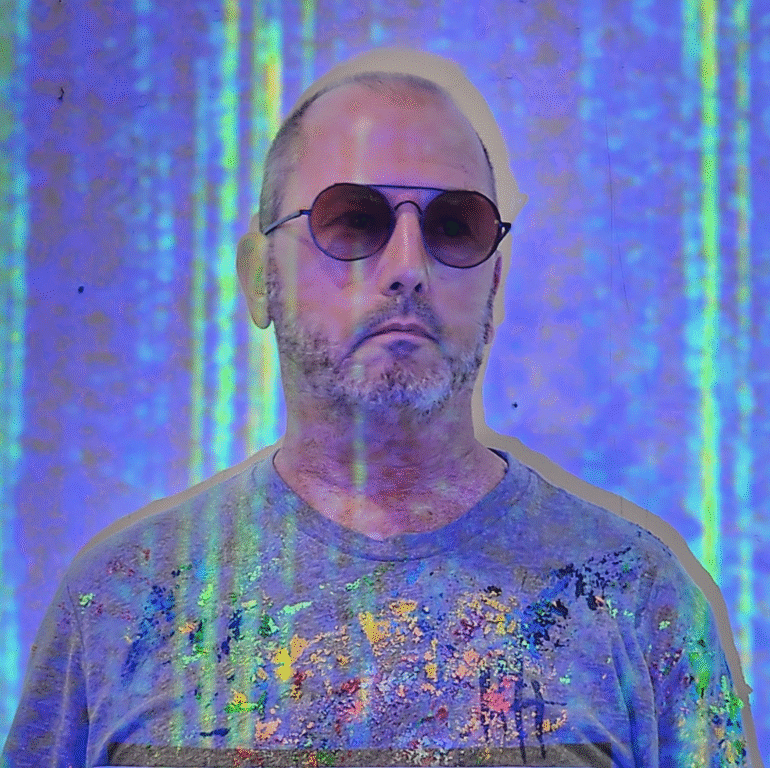

Bob Landström’s art lives in a liminal space between science and spirituality, material and immaterial. Known for his distinctive use of Earth itself as a medium–particularly pigmented volcanic rock–Landström creates textured, elemental paintings using a mix of traditional tools and ones of his own invention.

At the heart of his work is an inquiry into the nature of reality. Landström explores electromagnetic static as a pre-physical state, an invisible field from which the material world emerges. He builds custom devices to record electromagnetic frequencies, which he then weaves into sound-based and kinetic installations, merging light, movement, and raw earth into immersive experiences.

Based in Atlanta, Georgia, Landström studied fine art at Carnegie Mellon University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts. His background in electrical engineering–he holds both Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees–continues to inform and shape his singular artistic vision.

In this Culturalee interview, we delve into Landström’s creative process, his interest in Quantum mechanics and Native American petroglyphs, and his views on the metaphysics of material.

Your paintings are made entirely of crushed volcanic rock–a material with such a visceral connection to the Earth. What initially drew you to this medium, and how has your relationship with it evolved over time?

One day, I was in the desert in the American Southwest. I was looking at and photographing Native American petroglyphs–something that has always fascinated me. Not just Native American, but any kind of “rock art” like ancient cave paintings or prehistoric structures. Things that show this persistent human compulsion for introspective expression draw my attention.

In places like that, the Earth element is incredibly powerful. You feel it in your body, deep and unrelenting. I was infected, you might say, by that force. That area also happens to sit on a prehistoric volcanic deposit, from a time long ago when the landscape was entirely different. I brought a piece of that rock home with me in my truck. I didn’t have specific plans for it, or even a use for it, but over time I managed to make friends with the material, and it with me. I’ve used it ever since.

The way I work with it has evolved. I’m always experimenting with new tools and techniques, and I think the results have become more beautiful and more meaningful over time. Lately, I’ve even started using it beyond painting in experiential pieces that I’m developing now.

Many of your works deal with complex themes like plant sentience, dreams, and quantum mechanics. How do you translate these abstract or invisible ideas into visual language?

I’m probably pathologically curious. I stumble into rabbit holes, and when one piques my interest, I jump in with a shovel and dig as deep as I can.

I’m fairly balanced between left-brain and right-brain thinking, and I’m especially drawn to those areas where art and science overlap. Certain topics are like vast landscapes of brain food–places where imagination can really stretch out and run wild.

Quantum mechanics is a great example. I got caught up in a subfield that suggests, mathematically, that multiple simultaneous universes must exist, and not just one kind of universe but many different types. I imagined what it might be like to inhabit more than one universe at once, and how I could represent that in a painting.

Plant communication is another one, as you mentioned. I studied all the different ways plants communicate–not just with each other, but with things that aren’t plants. When I discovered that plants make sounds, my mind was blown. Then I started wondering: if plants have all these complex systems for communicating across species, shouldn’t we consider that a form of sentience? It’s intentional messaging toward a specific outcome. That’s sentience, right?

That led me to think about how we humans recognize sentience–maybe our standards are misplaced. Early humans likely understood this differently than we do today. All of that gave way to visual questions: How do you represent something like that? How do you paint it? That’s what I call sentient messaging.

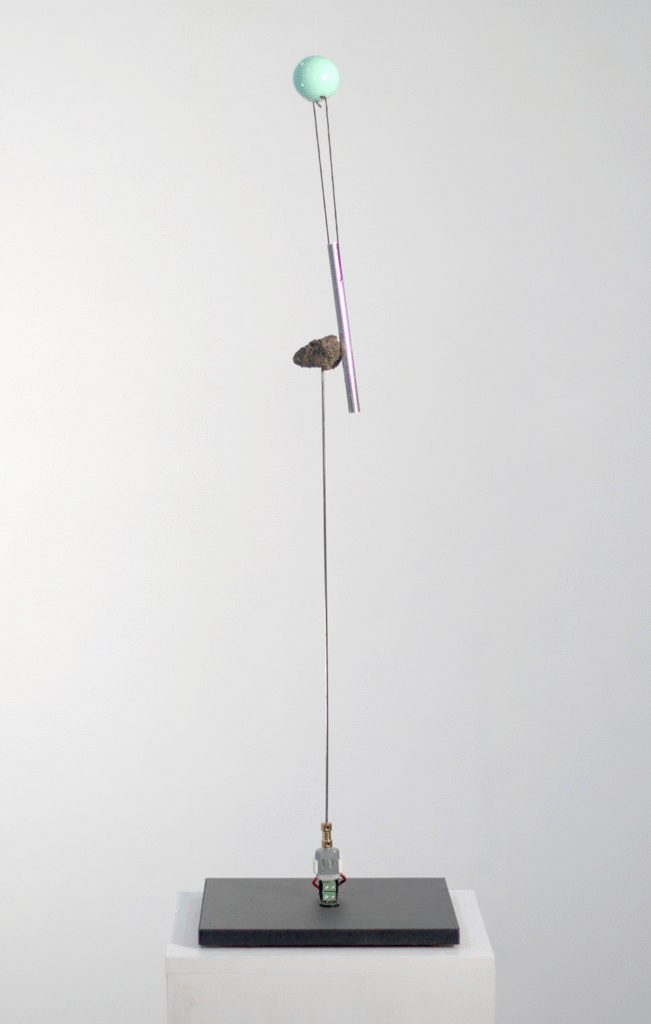

You’ve recently begun creating kinetic sculptures and incorporating soundscapes. What led you to expand your practice beyond painting, and how do these new mediums interact with your earlier work?

You’d probably classify it as a happy accident–but a profound one.

A couple of years ago, I attended an artist residency in Berlin. It allowed me to drop everything I’d been carrying and start fresh from a new and safe place. Creatively speaking, I found myself in a state I wasn’t accustomed to and couldn’t even name. It was a kind of radical receptivity I might not have allowed myself otherwise. No rules. Just stay open, without expectation, and hope your mind gets blown.

In that space, I started to wonder if painting–even matter painting–might be unnecessarily limiting. Once unbound, I realized the creative space was much larger than I’d been using up to that point. That shift made me think about my work as something more experiential rather than simply a two-dimensional, non-time-based object.

So I’ve been asking broader questions and experimenting more freely. I’ve been staying receptive to things like: “Does this work for me?” and “How far can I push this?” It’s a new kind of freedom and it feels great.

Your materials carry both symbolic and physical weight. Do you see yourself as more of an alchemist or an archaeologist when you approach a new piece?

More of an alchemist. I’m transmuting things into different states.

Materiality is very important to me, but I’ve been doing a lot of experiments lately with electromagnetic radiation, particularly static. I’m fascinated by that liminal space: the message between messages, before chaos collapses into order. I’ve developed a working theory that electromagnetic static is a kind of pre-manifestation state of materiality.

Could you talk about your process–from concept to completion–when working with volcanic rock? Is it intuitive, methodical, or something in between?

Well, there are a few dimensions to that. The concept stage is pretty consistent across all my work. My ideas are usually research-based. After reading or experimenting with something, I often end up with questions that start translating into images. Or, sometimes, I just want to play.

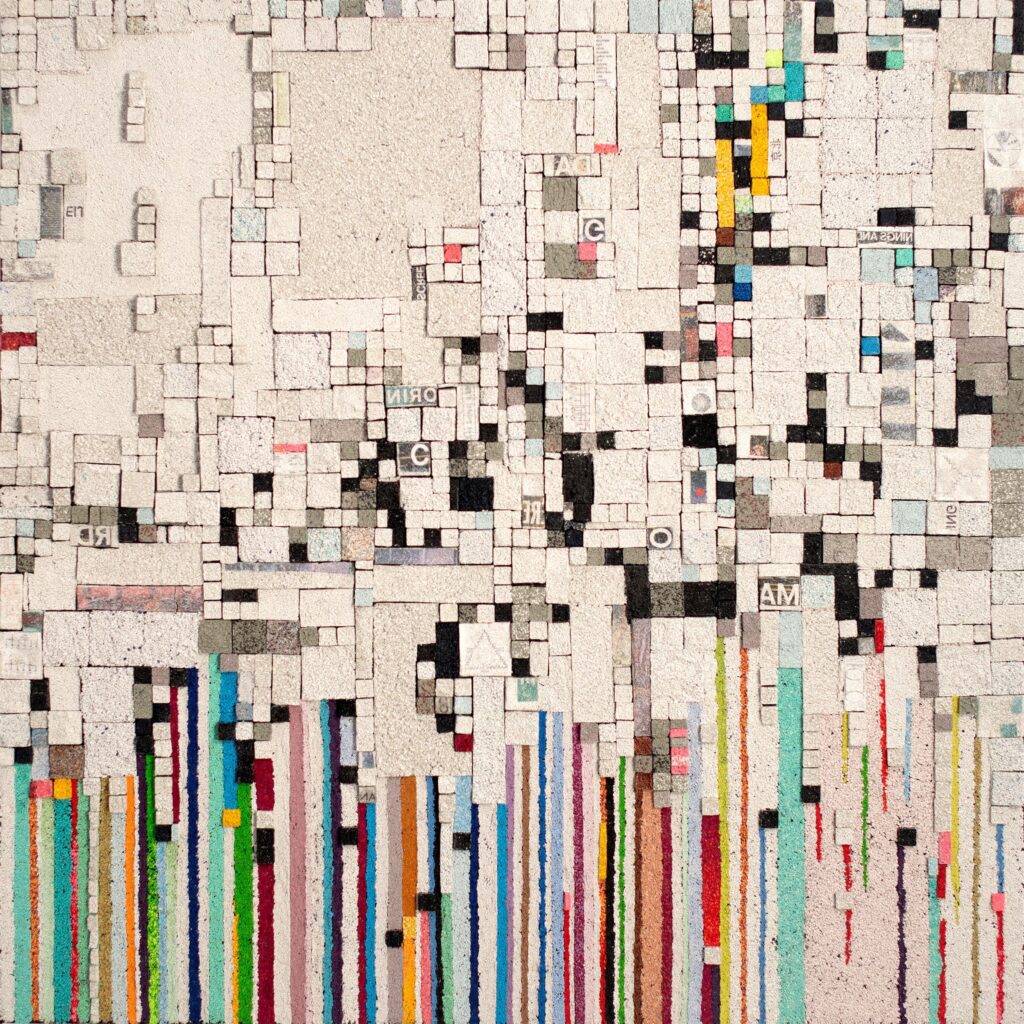

Because the material I work with hardens and becomes immovable rather quickly, I like to start with a good concept sketch. I often use the iPad for this stage; it makes “what if” studies easy and fluid.

Another key step is making the material I’ll paint with. I pigment the gravel before painting begins. This is a fairly involved process, since it involves different grain sizes of rock, different pigments reacting to the stone in different ways, and calculating how much of each color I’ll need. It’s a bit tedious, but it allows me to paint with a dry medium, which gives me a lot of flexibility with color. I can place a grain of green rock next to a grain of red rock, and it won’t turn to mud, for example. There is also the opportunity to sculpt the surface and to use the depth of surface as part of the composition. After years of working this way, I always have a large inventory of colors and grain sizes ready to go at any time.

The painting stage is the most involved. I mix colors by combining different rock sizes and colors dry, in a bowl or bucket. Then I add a polymer emulsion that binds the grains together and to the canvas. The result is a kind of sticky gravel, and I use a trowel, knife, or custom-built tool to apply it. Brushes won’t work with this medium. The mixture lets me sculpt the texture, form, and chroma all at once.

Most of the painting happens with the canvas laid flat, either on a table or the floor. Otherwise, the material falls off the trowel before it hits the surface. For canvases larger than sixty inches or so, I suspend myself on a swing from the ceiling so I can float over the work, moving the canvas underneath me as needed.

The polymer emulsion, when wet, makes the surface look milky. I have to look past that muted color and imagine what the final colors will be once it cures and becomes clear. Sort of like painting into the future. There’s no real way to slow the curing time, so after a few days the material becomes fully set and no longer painterly. If I’m not finished by then, I throw the piece away and start over.

Esoteric studies and frequencies are a recent focus in your practice. How do you approach integrating the intangible, like sound or metaphysical ideas, into a physical art object?

The metaphysical aspects of a piece are experienced—or conjured—by the piece itself. Sound is physical, but many metaphysical phenomena are expressed through corresponding frequencies of sound. Some of my kinetic experiments can be heard because they include electromotive components. Others are kinetic, specifically to generate a particular sound. Even when sound isn’t the focus, the movement and visual presence of a piece contribute to the overall experience it creates.

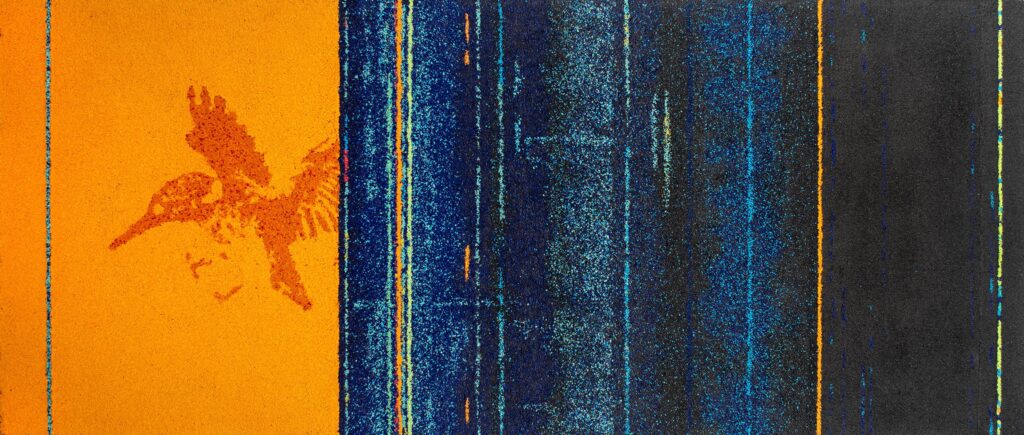

Metaphysical qualities can also be amplified through the choice of materials. I often use volcanic rock components in my work because of their inherent material and alchemical properties–the same reason I use them in my paintings. In my digital work, I gather or generate radio signals at intentional frequencies, using them to create textures and rhythms that feel emergent–arising from the interplay of frequencies themselves.

You’ve mentioned interest in plant sentience. What role do you think non-human intelligence plays in your work, and what are you hoping viewers walk away with regarding that?

I had a series of works titled Florum Somnia, which focused specifically on plant sentience and what might happen in plant dreams. That experience brought the broader idea of sentience more fully into focus for me.

It made me realize how arbitrarily humans–at least, in the West–have defined sentience. We’ve set ourselves as the standard, but who’s to say that’s the only kind? Sentience could take very different forms in different beings. Where it starts or stops, who knows?

I think it’s risky to assume we’ve got it all figured out. You have to leave room for horizons to expand.

As you prepare for your exhibition at Alday Hunken Gallery in Atlanta, are there any specific pieces or themes you’re most excited to share with the public?

The theme of this exhibition is Grit. My painting medium is literally gritty, but more important is the figurative meaning of grit: the persistence to show up when the work feels thankless. The raw urgency of creativity when no one is watching, when no one witnesses the process. The fortitude to keep going, to resist letting the practice become static.

It’s also about asking yourself the hard questions without expecting to know the answers.

With your unique blend of science, spirituality, and material experimentation, do you see your art as a kind of inquiry or research process?

Can it be both? I think it is both. Inquiry sparks research and research inevitably leads to more questions. It’s a loop—a reflexive process where one feeds the other. Sometimes the work begins with a curiosity, a flicker of wonder. Other times, I follow a line of action or experimentation and only later realize what I’ve been asking.

In that sense, the studio becomes a space for listening as much as making. What begins as a question might resolve into a gesture, a form, or a sound, or it might remain suspended, unanswered, and still vital. The art can emerge at any point along that arc.

Looking ahead, are there any new territories, either conceptual or material, that you’re hoping to explore in future works?

I could go on for days with that question. As I move beyond the idea of an artwork as something that simply hangs on a wall, almost everything you can see, touch, hear, or even smell, starts to feel like material for the work.

My newest series of paintings is evolving in its own direction, but much of my practice is shifting toward something more experiential. It’s about moving beyond just seeing into a multi-sensory presence. The canvas becomes circuitry that generates sound or light. Materials expand into machines, radio electronics, mechanical systems. My tools now include software and a soldering iron.

I’m still finding my way through the forest, but I’m following a strong pull toward works that are lived, not just looked at—toward a practice where the art is something you step into, sense, and feel.