In 2026, internationally acclaimed sculptor Cliff Garten will unveil four new public artworks across the United States, including a major installation in Burbank, California. Known for his sweeping integration of sculpture, infrastructure, and landscape, Garten has spent decades reimagining what civic art can be—not merely adornment, but a catalyst for connection, reflection, and transformation in the built environment. As cities grapple with questions of identity, accessibility, and the evolving role of public space, Garten’s work offers a compelling vision: public art that not only inhabits space, but fundamentally reshapes how we experience it.

In this exclusive Culturalee interview, Garten shares his insights on the power of sculpture in civic life, the ideas behind his upcoming installations, and how each piece reflects his belief that public art must do more than stand out—it must speak to and for the communities it serves.

You have four new public artworks scheduled for installation in 2026—in Burbank, CA; Las Vegas, NV; and two in Denver, CO. Could you share how each of these projects reflects your vision of public art and how they will transform the public spaces they inhabit?

All of these projects are major cultural venues in these cities, where the sculptures will have a permanent residence. My civic sculpture is activated through public activity, but it also creates activity in public places. A strong public space, regularly programmed for civic use, supports the artwork—but the reverse is also true: the artwork helps generate vitality in that space. This is the energy people are after when they commission civic sculpture. The nature of the place itself guides how I develop each sculpture.

Each of my four new projects is part of a major cultural venue in their respective cities: Denver, CO; Burbank, CA and Las Vegas, NV. My civic sculpture is completed through public use, but it also creates its own activities in public places. A space with a clearly defined architectural or public program makes it easier to respond. The places where the work is installed are my guide for how to develop the sculpture for those places. For the redesigned historic Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport, I created sculptures called The Two Electras. The paired sculptures reference the aerodynamic forms innovated at the airport site from 1920’s -1950’s. The Two Electras are named after the Electra 10E flown by Emilia Erhart and designed in Burbank. The Two Electrasdraws on the streamlined forms of early aviation, transforming them into a more ethereal order of shapes by introducing transparency and light. Their complex LED light shows, put them in a lineage with the California Light and Space movement. The Two Electras reference the beauty and mystery of aeronautical forms designed at Burbank Airport, marking it as a site for significant developments in the history of early 20th-century flight and a hub for air travel in the 21st Century. The pair of sculptures with seating pedestals create the space of a plaza and flank the entry of the new airport. They are also pivot points for activity at the terminal and create their own small plaza area. Like all my work, the references to the site and its history are subtle. The references to aviation are about primary forms and are subliminal. They reference something about the site without spelling it out. The work is not didactic, the real interest has to be in the sculpture. The pieces come alive at night when they are programmed with complimentary colors that alternate between the inner and outer forms and the pairing of the two sculptures. I have been waiting for the LED technology to catch up to my illumination strategies for the sculptures. Lights are now small enough and powerful enough to do what I want.

The inner and outer forms are built of layers of vertical ½” stainless-steel rods. The forms are transparent containers for sunlight during the day and LED light at night. As someone moves through the plaza and their position changes in relationship to the sculptures lines, moirés patterns appear. This is a structural and visual strategy I began to work with in 2010. The largest sculpture I have created with this structure will be installed in Las Vegas for the largest public art commission the City has ever done.

The City of Las Vegas is building a Downtown Civic Center Plaza. My sculpture Harmonic Ascension, a 30-foot-tall stainless steel piece, will stand at the center of this new civic space. The City Hall, the Civic Center, the Municipal Court, and a new parking structure, all frame a plaza designed for concerts and public events. The work unites these buildings and acts as a symbolic centerpiece for a new kind of civic identity in Las Vegas—distinct from the entertainment strip that has long defined the city’s public image.

The sculpture is composed of ½” stainless steel rods that form a transparent volume—a register of changing daylight—while at night, it transforms under the shifting color of LED illumination. This duality between day and night and their two different looks is a recurring strategy in my work. The form itself is based on a transformation: it begins with the silhouette of a violin and spirals upward, morphing into the shape of an electric guitar. You would not recognize these source forms at first glance; instead, what you see is a wild, spiraling figure that evokes motion and rhythm. Created for the Entertainment Capital of the World, it elevates familiar cultural forms into something unexpected and iconic. I believe Harmonic Ascension will become a landmark for the Downtown Civic Center Plaza, offering a unique identity rooted in civic—not commercial—culture.

In these upcoming landmark projects, how are you integrating sculpture into the architecture, and landscape of the locations? Can you talk about your approach to embedding your work into the lived experience of these spaces?

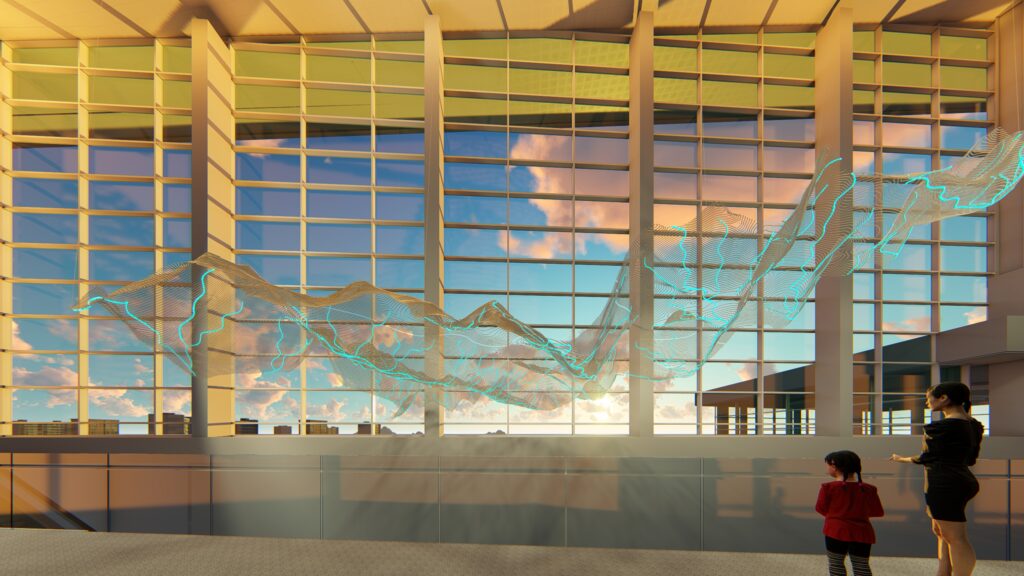

A good example would be Mountains and Rivers Without End that is suspended in the western lobby of the Colorado Convention Center in Denver. The sculpture quietly marks time, echoing natural systems, and reminds us that we are always connected to the geography that sustains us. Unlike the outdoor sculptures, which must be built with rugged durability, this piece allowed me to work with a lightness and delicacy. It is a suspended veil, 120 feet long, inspired by the nearby Front Range of the Rockies. Visible through the building’s glass façade, that distant mountain range became both subject and frame. The sculpture traces 120 miles of topography of the Front Range in laser-cut aluminum lines and blue glass rivers—mapping Denver’s watershed and calling attention to its diminishing snowpack. It is a floating diagram of environmental interdependence. The sculpture’s diaphanous form underscores the fragility of the water cycle in the arid western U.S. People walk beneath and alongside it on their way to conventions, performances, and everyday city events. At its highest point it is 70 ft above the floor, you move under it on the escalator and then alongside it on the mezzanine. Its scale and translucency allow it to be both present and permeable. Light plays across its surface throughout the day, constantly shifting the viewer’s perception. From certain vantage points the mountains can be seen through the veil of the sculpture.

This work uses the concept of borrowed scenery—in Japanese landscape design, this is called a shakkei. A distant view, like a mountain range, can be integrated into a smaller garden to create a much larger sense of space. At the Convention Center, the sculpture allows the viewer to see the Rockies through its layered forms of aluminum topo lines. It invites a moment of environmental reflection: Denver’s water comes from that snowpack, and their future depends on it. The poetic narrative of the piece asks us to look at our shared environmental truth.

You have often spoken about the importance of dialogue in your practice. How do community voices influence your creative process, especially when developing permanent public artworks?

When doing civic artwork, the first step is listening to the community—or whoever is commissioning the piece. This is not like working alone in a studio, where you author everything by your own directive. Listening is crucial. Sometimes what you learn most clearly is what not to do. I listen not just with my ears but by sensing the energy of the place through its people. Communities bring me in because they believe I can do something meaningful; I have to earn and keep their trust. Over time, I have come to realize that I am channeling a collective vision into the work. That can be deeply inspiring—and also exhausting.

For instance, with the I Am A Man Plaza in Memphis, commemorating the 1968 Sanitation Workers Strike and MLK’s legacy, the pressure to “get it right” was enormous—much of it self-imposed. The timeline was brutal: nine months from concept to installation for the MLK50 celebration of 2018. But once community engagement is complete, there is a moment when I say: Now I will do what you brought me here to do for you and you need to trust that.

Places themselves hold power. They are palimpsests of memory—everything that has happened there lives in the ground and material quality of the spaces. I respond to that: the geology, the urban form, the sunlight, the material language of the place. For example, Huntsville, AL sits on karst limestone, part of the Appalachian Valley geologic area. Water runs through this porous rock into a spring at the center of the city where the City was founded. My sculpture at Huntsville’s new City Hall celebrates that: it is composed of 20,000 blue glass crystals, marking the source of the city’s water and its identity.

In large-scale projects, I often juggle three clients: the public art agency, the municipality, and the architectural design team. Each comes with competing timelines and goals. The artist has to hold the center—meeting deadlines, adapting to site constraints, but also preserving the integrity of the vision. Construction is always messy, but compromise does not have to mean loss of meaning.

The new piece planned for the National Western Center in Denver marks a move away from abstraction toward more figurative work. What led to this shift, and what does this new direction allow you to express that abstraction may not have?

Part of why I was selected for the NWC project was my background in landscape sculpture. The site is massive—110 acres—with year-round use. The project experienced budget cuts, and what we ended with is far from where we began. Still, the mission of the National Western Center stayed compelling: “to convene the world… in pursuit of global food and water solutions.” At the same time, the Stock Show—a deeply embedded tradition—draws families and celebrates ranching culture. I am allergic to horses, so this was not my home turf. But I began asking: who is my audience? How can I expand their understanding of the mission?

I wanted to challenge the mythology of the West while still honoring it. This includes Hollywood’s cowboy myth, yes, but also the lived reality of ranching communities. I spoke to ranchers—men and women. Women are as central to that life as men. That is why the sculpture is of a mixed-race cowgirl. She is in a shifting, dynamic relationship with a bull. The sculpture is anchored at each end with traditional Western-style figures, but the center becomes a zone of transformation. It is figurative, yes—but that figuration destabilizes itself.

This shift to figuration was a challenge for me. I brought in digital modelers and have an excellent foundry team. At times I wondered if I could pull it off. Early concept sketches were, frankly, not up to my own standards. But Denver Public Art supported the risk and backed me fully. The finished work is both inviting and charged. Kids will love it—it is tactile and interactive—but it also carries weight. It asks difficult questions. The heroic allegory becomes a “heroic question.”

The sculpture is 20ft long and 7.5ft tall. Approached from either end, it looks like a classic figurative sculpture. But at the center, something more complex is happening—something unsettled, and more urgent. Figuration draws people in because it is familiar. Once they are engaged, the piece is asking them to look again.

Public art can often become a touchpoint for collective memory and identity. How do you design artworks that resonate with the specific histories, cultures, and future visions of the communities where they are placed?

The very first thing is to get a feeling for the place. Once I am confident about my relationship to the community and the site, the sculpture elicits from that point. The second thing is that my response about the content of the work is not direct. Generally the work locates you in the space and works at a subliminal level. I get people comfortable first and then make the content available. Some pieces are dramatic, but that drama gives way to an exploration of the more subtle content of the piece. My responses are as diverse as the communities themselves. Each project responds to its own context—historical, cultural, ecological—and the people who inhabit it. I work hard to uncover the unique character of each place and to build a sculpture that reflects and enriches that identity.

With your 2026 works being sited across quite different urban environments—from Burbank’s media corridor to the evolving cultural infrastructure in Las Vegas—how do you adapt your artistic approach to reflect the unique character of each city?

The work I create derives meaning from the site where it is permanently installed. One day I may be designing an airport, the next for a bridge or a civic plaza. Adaptation is not quite the right word—it implies altering my process to fit. Rather, the process begins with listening to the place. I ask: what is this place? What are its layers—physical, social, and environmental? What are the problems and what are the opportunities?

Reading a site and seeing the narrative within it is a skill I have always had. It involves understanding how the physical aspects of the site derive their form from the underlying narrative from the place I am working. Questions like, what is the angle of the sun throughout the day, what kinds of activities happen there, how people move through it, what are the site’s social histories etc. I am always thinking about how sculpture can be a partner in those patterns—reflecting sunlight, drawing people in, offering moments of pause or interaction. The environmental and social histories of places are as much my materials as the materials– steel, bronze and concrete that I use to make the sculptures.

There are some materials and processes that repeat themselves in my work as I develop the sculptures. The structures you see in Burbank and Las Vegas are part of a series I began in 2010 with a piece called Sentient Beings in North Hollywood, CA and then evolved into Ethereal Bodies, at the Zuckerberg Hospital and Trauma Center in San Francisco. These sculptures and others are volumes that contain light, both sunlight and LED light. They are made of stainless steel and the formal strategy is one I continue to work with because of my interest in illuminated volumes. Their form language is continually changing as I modify the sculptures for different places.

Your work often blurs the boundary between sculpture and infrastructure. How do you envision this interdisciplinary approach evolving with these new projects, particularly in Denver and Las Vegas?

The four 2026 projects are more focused on placemaking than infrastructure per se. That said, my practice has always argued that infrastructure can be expressive—it does not have to be cold, inert, or purely functional. Infrastructure gives sculpture the possibility to operate across space and time, integrating systems within the city.

Bridges are where we have most clearly demonstrated this. Infrastructure projects typically fall into three categories: short-term fixes, 75-year rebuilds, and 100+ year investments. Right now, across the U.S., we are facing a wave of aging infrastructure in the 75–100 year range, primarily our bridges. If we are going to rebuild these structures, why not invest in making them beautiful?

Engineers build the public realm, and they do so with admirable efficiency. But they are not trained to ask aesthetic or poetic questions. That is where artists can intervene. I have long dreamed of a contemporary version of the Works Progress Administration—where infrastructure creates not only jobs, but meaning and identity.

Bridges are especially rich opportunities. They can link communities. They can act as gateways. They can offer distinct experiences at different speeds—whether you are biking across one, walking under it, or seeing it flash past at 60 miles per hour. Each experience is an opportunity for engagement with material, light, and form.

If you look at Foliage in Kettering, OH or Bridge of Land and Sky in Oregon, you will see this: the work is shaped by its setting. Foliage sits in a hardwood forest where the spaces are tight, the other in open rolling hills beneath dramatic skies. Each responds to place and function—then elevates function into something that is sculpturally expressive and regionally grounded.

So, the question becomes: If we are spending public money on infrastructure, shouldn’t we build something that engages us—something we are proud to live with for the next 75 years and does not make us feel like we are in prison every time we cross it? Investing an additional 5 to 20 percent to transform not just the function, but the experience of infrastructure challenges the entrenched frameworks of engineering practice, municipal bureaucracy, and political will. But unless we believe—culturally and collectively—that it is worth spending that money to shape a more meaningful, beautifully built environment for ourselves and future generations, it simply will not happen.

In what ways do you think public sculpture can challenge or expand people’s understanding of civic space, especially in a time of growing political and cultural fragmentation?

The most important thing is that we have public spaces—spaces dedicated to shared civic life, interaction, and democratic presence. The French concept of l’espace public points to something broader than plazas or parks—it implies that the city itself is a space for dialogue, a place where difference and commonality can coexist. In the U.S., our public realm has often been more fragmented and commercialized, and now, much of our so-called public discourse has migrated to digital platforms that are neither physical nor truly public in the democratic sense. That makes actual physical public space more essential than ever.

Sculpture in civic space has the power to reassert the character of a place. It can reconnect us to our bodies, to each other, and to the ground we stand on. My work is intended to activate the space it inhabits—not just visually, but physically and emotionally. It invites people to pause, to gather, to reflect, and sometimes just to play. Those moments of presence and interaction are not insignificant. They open the door to empathy, to shared experience, and to a deeper awareness of our roles within a community.

I began my career making objects for galleries and museums, where the object exists independently of its surroundings. But public work is entirely different. In the public realm, the work must accommodate weather, wear, and time. It must account for people walking, sitting, or simply passing through. Public work needs to withstand a certain amount of public abuse, although I have never had a piece vandalized, I am diligent about making the work as low maintenance as possible. Many of my sculptures incorporate seating, pathways, or light. These are not accessories, they are essential to the experience. I seek the poetry in our everyday activities that public places and infrastructures accommodate.

There are also limitations—technical, political, and practical—engineering has to be solid and often it will alter forms. And there is always the maintenance issue. One of the rules I follow is what I call the “beat it with a chain” rule. If someone were to beat the sculpture with a chain, and it still looks good, then I have done my job. Elegance and resilience must coexist in public space.

Good public sculpture meets people where they are. It does not require specialized knowledge or exclusive access. It offers something immediate, something visceral, but also opens a space for deeper questions—about identity, history, ecology, or justice. In a time when our social fabric feels increasingly frayed, I believe sculpture can help hold space for complexity. It does not resolve contradictions, but it can make them visible, legible, and worth sitting with.

Public art, at its best, does not just adorn a city, it helps define it. It creates a shared experience that can outlast the news cycles and remind us that we still live together, in place and in time.

Looking ahead to the unveiling of your 2026 projects, what do you hope viewers will take away from their interaction with these works—not just aesthetically, but socially and emotionally?

What I hope people take away from these new works is the sense that sculpture can shape how we experience the world around us, how we move through space, how we relate to each other, and how we understand our environment. Each of these pieces—whether it is referencing the history of aviation in Burbank, translating sound into form in Las Vegas, tracing the fragility of snowpack in Denver, or reimagining Western iconography at the National Western Center—is meant to create a layered experience that feels both immediate and enduring.

Each new project brings an accumulated knowledge forward. They draw from the materials and rhythms of each site and are designed to open a dialogue—sometimes subtle, sometimes direct—between the sculpture, the viewer, and the larger civic context.

I have always looked to infrastructure—not just as a technical system, but as a cultural one. That perspective has shaped much of my work over the years, and I see it as a way of expanding what sculpture can do. These four new pieces are more about place making than they are about infrastructure systems, but they are still built into the daily life of their cities. They create continuity between the functional and the poetic. They ask how we want to inhabit public space—and what kind of presence we want to leave behind.

In the end, I want these works to offer something that stays with people—not just as an image, but as a memory of place, a question, or even just a moment of pause. That is the kind of resonance I aim for. It is not about a single message but about creating space for meaning to unfold.

All images courtesy of Cliff Garten Studio.