In this edition of Culturalee in Conversation With, we sit down with Amy Rose, the visionary lead curator behind Undershed, one of Bristol’s most dynamic and unconventional art spaces. Rapidly gaining a reputation for its bold programming and commitment to platforming emerging voices, Undershed has become a vital part of the city’s cultural fabric. Amy shares her curatorial approach, the ethos driving Undershed, and what it means to create space for art that challenges, questions, and connects.

Prior to joining Undershed as Lead Curator, you co-founded immersive studio Anagram. How did you get involved in Undershed?

I got involved in Undershed when it was a twinkle in the eye of the amazing team at Watershed in Bristol.

Hidden behind the cinemas and the cafe / bar – the Pervasive Media Studio was started in 2008 as a supportive R&D space for those working with creative technology. I joined the resident community of artists at the Studio in 2013 with my Anagram colleague May Abdalla – and our practice as filmmakers was totally transformed through the collision with such a vibrant and inspiring place.

Being a member of the studio community for ten years meant that I knew the building and the people very well – and at the same time, the world of immersive and interactive art was growing rapidly, despite there being few opportunities to show work on an ongoing basis outside of the festival circuit.

So, in 2022, a conversation sprang up in the Watershed bar between myself, Jo Lansdowne (Exec Producer of the PM studio) and Mark Cosgrove (Cinema Curator) – and I began some research into what Watershed might do if it had a gallery for showing immersive and interactive art alongside the three cinema screens.

Slowly, we built up the ideas of what it could be and raised the funds to transform the space – and I left Anagram in autumn 2023 to fully step into my role as Lead Curator of Undershed.

You have a background as a documentary filmmaker and graduated from Edinburgh College of Art with an MFA in directing. What led you towards immersive art, and how has your background shaped your curatorial approach?

Drawing together the past threads of how we come to our present path is always a complex process. I did originally train as a documentary filmmaker – making short films and working on feature documentaries as an assistant producer and cinematographer. I was interested in films that felt like a creative treatment of reality – that got into the heart of people’s lives and internal worlds with sensitivity and a bit of magic. But the documentary industry wasn’t a very easy place to be a young woman with weird ideas, and I also did a lot of interactive game design outside of work for music festivals and on children’s wild camps. That culture of resourcefulness and fun that permeates the UK music festival scene and the progressive outdoors education movement I’d been part of since I was a child (Forest School Camps) has always been a big source of inspiration and learning for me. These are open spaces of radical experimentation where you can try things – and fail – and you are forced to use simple tools for maximum impact.

When May Abdalla and I started making work together under the name Anagram, it felt like we were cooking up that sense of deep experimentation and ingenuity with the rigor and heart of documentary film. We would go to film festivals and be inspired by places like IDFA Doclab (every November in Amsterdam) and Sundance New Frontier Lab (no longer in this world) – always hunting for ways to experiment with narrative, interactivity and meaning. I worked with May for over a decade, and we made many projects that toured all over the world, always experimenting with form and mostly working with creative non-fiction.

Personally, I love the work that tries to speak to your whole body, with all its capabilities and complexity. That means moving beyond the audio-visual to involve your other senses, whether that’s the way you move, what you touch or the whole environment in which the piece happens. I’ve long been fascinated by how emotional and intellectual depths can be found through movement and sensation alongside thinking – challenging the approach to meaning-making that has dominated Western philosophy and culture for hundreds of years.

If I try to distil how these things all thread together into a curatorial approach – I would say it’s really about a combination of deep thoughtful intention alongside an experience that feels playful and accessible. Ultimately, you need both elements to actually reach people, and touch what’s going on under the surface.

Undershed is Bristol’s first immersive gallery — what was the vision behind launching it?

Undershed gathers together interactive work by renowned artists from the UK and across the globe. Artists have been making this work for a long time now – but it is rare for audiences to have the chance to build up a deep understanding of the form outside of large-scale spaces like Outernet or The Lightroom.

Importantly, Undershed is a gallery built inside a much-loved and long-respected independent cinema – Watershed. Within this context, Undershed offers audiences a pathway beyond the silver screen, and shows that good storytelling and brilliant conceptual thinking can be crafted into new artworks, with new tools.

The description “immersive gallery” is something we’ve debated many times – there’s a latent feeling in the air that the word “immersive” has been used far too much, inviting raised eyebrows and subtle sidestepping. The funding scheme Immersive Arts, which Watershed is involved in running, describes “immersive” in a helpful way – as “art made with technology that actively involves an audience”. This is the best boundary to set around a medium that is undisciplined in form and agnostic in technological approach.

We want to share work that has emotional depth. Where interaction is involved, the conceptual thinking behind the work has to be challenging the notion of what it means to participate in an experience or a story. There is no interaction just for the sake of it – no gimmicks using cool new tech. This is about quality, and experiments carried out by artists who are right at the vanguard of this exciting form.

Of course, the task of building a new space is as much about what artwork we put in it as it is about all the elements at play – what it’s made of, who the front of house staff are and how they talk to people, what the atmosphere really feels like when you step into the room. What we’re really seeking is a space that feels both playful and serious – comfortable and theatrical. A space to laugh and talk to other audience members, as much as it is a space to meditate on life and the complexities of our relationship with the world around us.

Can you describe the concept behind the new exhibition FRAMERATE – Pulse of the Earth?

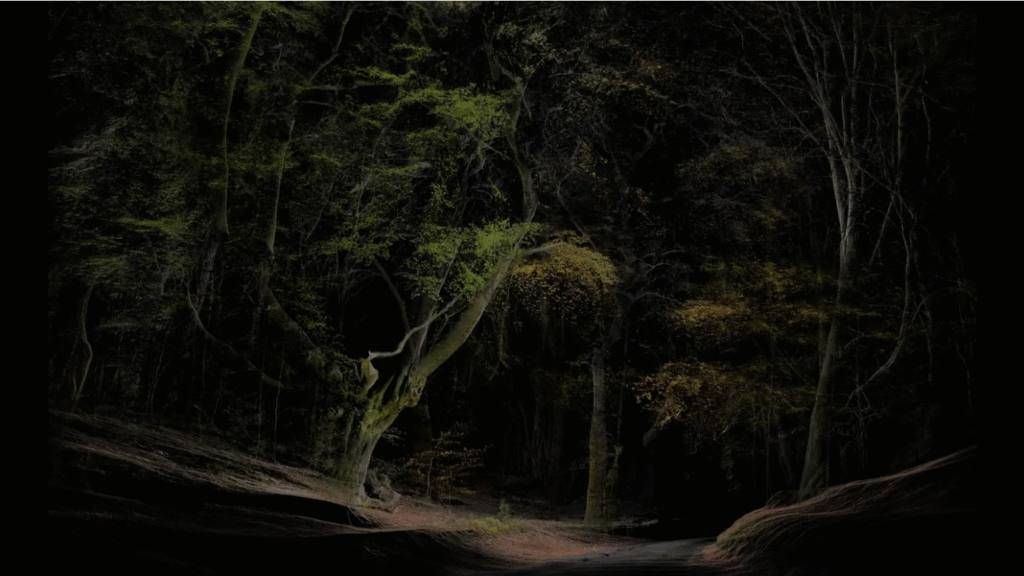

FRAMERATE is a piece that has been celebrated widely on the film festival circuit, from Venice to London to Tribeca, made by a brilliant UK-based studio called ScanLAB Projects. It was clear that this piece would work for many reasons: the beauty of the overall experience; the philosophical approach to challenging our notions of time and human impact; the rigor in artistic approach and method.

Due to its scale, and the meditative nature of how you engage with the piece, we decided that FRAMERATE should take over the whole of the gallery. In cases like this where a single work dominates the physical internal space, we try to build a programme around it to maximise the impact and offer alternative pathways into the questions at the heart of the work – and in this case that is a season called Step to the Earth.

What inspired the theme of this exhibition, and how does it connect to the natural world or current environmental concerns?

Bristol has one of only four Green Party MPs in the UK, and there has long been a sense that this is a city that cares about the climate crisis. Programming work that can open up contemporary conversations and feel relevant to people is an important element in how we choose artwork in Undershed.

As FRAMERATE plays within a wider season it is as much about the complementary cross wires that connect the works together as how they play individually. Everything in this season explores our own personal relationships with the land we live on through new forms of storytelling, tuning into the pace of change we often miss and the details of life on earth that are usually invisible to the human eye. Ultimately – as coastlines erode and floods escalate, the season explores how artists can help us grapple with these difficult questions.

How did the collaboration process work with the artists and technologists involved in creating FRAMERATE?

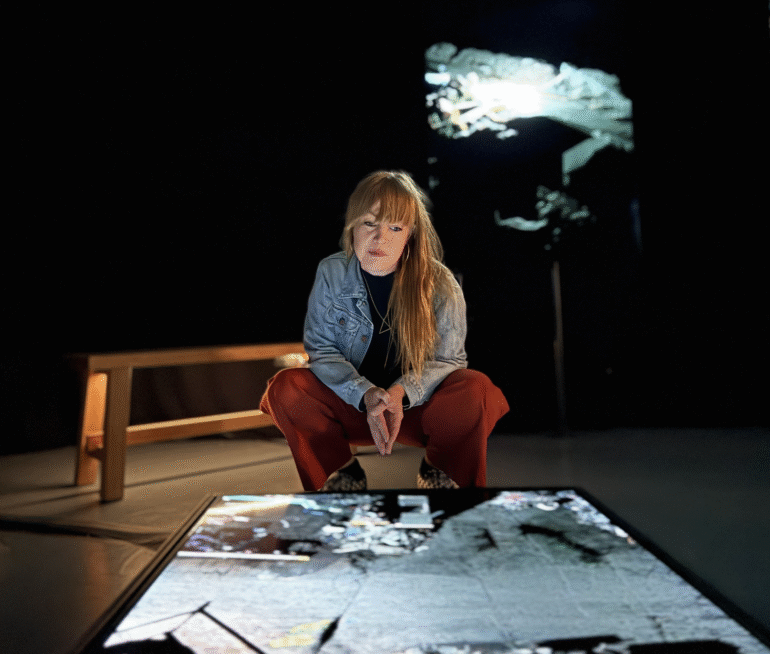

FRAMERATE is a piece that has travelled already – so the collaboration was focused on how to realise it with the available space, to achieve the best experience for audiences. Our teams worked closely together on how to install the piece, but the main bulk of the creative work was finished some time before it arrived in Bristol. The nuances of where the screens are in the room, what people can sit on, how dark it is – these things, of course, all matter hugely, and we try to bring meticulous attention to detail when considering every element of experience design.

Were there any specific challenges in bringing this immersive exhibition to life–either technically or creatively?

The challenges around exhibiting immersive work that uses new technologies can be really varied – and sometimes they centre around the way an audience understands (or doesn’t understand) what they’re experiencing. This might mean the way the technology works – or the process enacted by the artist to produce the work. While an artwork needs to work and be impactful without a deep understanding of process – sometimes, if a new technology is involved, helping the audience get to grips with what they’re looking at can really deepen their connection with the ideas in play.

FRAMERATE is, in one sense, a simple timelapse piece that explores the impact of human industry and the forces of nature on landscape – but where some audiences might think they’ve seen timelapse done before on TV, this was made using an entirely new process involving LiDAR scanning. LiDAR is a remote sensing technology used by surveyors, architects and video game designers.

Once a LiDAR scanner is set in position, it shoots out millions of laser pulses in all directions, creating a 3D replica, or digital twin, of the place. You can then look at this 3D space from any position – up in the air, down on the ground, at a very specific stone, etc. FRAMERATE turns these digital 3D maps into 2D films, with various points in space chosen by the artists to be seen in the artwork.

The reason LiDAR is interesting, beyond the beauty of the imagery, is partly rooted in the incredible level of detail captured by the laser pulses – but also because of who is using it, and how it’s being used. The artists from ScanLAB talk about LiDAR as the future of photography, highlighting its increasing ubiquity across mobile phones, driverless vehicles and various forms of surveillance. This is one of the major new tools of our time – perpetually recording the world around us to a level of detail that has previously been impossible. What is done with that level of detail in future remains to be seen – but there is ample reason to imagine that it could be manipulated or weaponized in all sorts of ways that are currently invisible. The key challenge in presenting FRAMERATE is how to have this conversation with audiences around and after they experience the work itself – enabling people to grapple with this technology and meet it on their own terms.

What kind of emotional or intellectual response do you hope Pulse of the Earth will evoke in visitors?

I think the main thing I always hope for is that audiences are moved by the work – that it touches them, underneath the surface of their everyday modus operandi of moving through the world. And because of that emotional encounter, people form memories that really stay with them,and continue to provoke thoughts and sensations in the weeks and months afterwards.

With FRAMERATE, what happens for me is that I have a very sensual encounter with being in a shifting tidal frame. It feels like being in a kind of ocean – with rippling images and moving coastlines, shadows of people and pumpkin vines bursting into being. This is both beautiful and altering, pushing me out of my habitual mode of perception to feel into another way of being in relationship to the world around me. I often think that what immersive work does really well is craft attention – and the experience of participating in something can alter the way you pay attention. In this way, it can be deeply personal and intimate – and about how you engage with things – as well as being about a story or something tangible in the world.

How do you see immersive experiences like Pulse of the Earth shifting the way audiences engage with art?

I am not someone who will make huge claims about immersive technologies changing the way people engage with art, or with stories. I am really interested in how new tools enable new forms of storytelling and experience design – but I think the fundamental underlying relationship being set up stays the same. And by that, I mean the relationship between people – between artists and audiences, between ideas being offered and the experiences that unfold.

Immersive techniques have been used for hundreds of years already – you can see the same ideas about space, the position of “the audience” and meaning-making in cathedral design from medieval England. And, of course, new tools beckon new techniques – but I still love going to the cinema or losing myself on a dancefloor with a giant sound system. The question remains – who are the artists using the tools, and what are they really trying to do or say?

What’s important is that we don’t use immersive (or, experiential) techniques to simply escape from the realities of our changing world and political context. The vital role that artists play in contemporary life is something I will always champion and defend. I hope that with the development of more spaces that can show immersive and experiential work, audiences can build more literacy around this form of art – and expect more than pure spectacle.

Bristol has a rich creative culture — how does Undershed fit into or challenge the local art scene?

There has never been a space dedicated to artwork that uses new technologies to craft active participation in Bristol. Immersive and experiential work presents particular challenges for the teams presenting the work – and for audiences when embarking on an active journey in their participation – so it makes sense to build understanding of what to expect and how to feel comfortable in one, contained space. Brilliant other places obviously exist that show beautiful artwork – but this fast-developing form needs a home, and now it has one.

From a Watershed perspective, the Pervasive Media Studio has spent 17 years investing in the community of makers and researchers involved in this work – and only very few of those people have had the chance to show their work at home, in Bristol. Creating a space where some of that work can meet audiences in a carefully crafted way is really positive for that community.

Find out more about The Hothouse Laboratory, the latest exhibition at Undershed which runs until 1st September 2025 here.