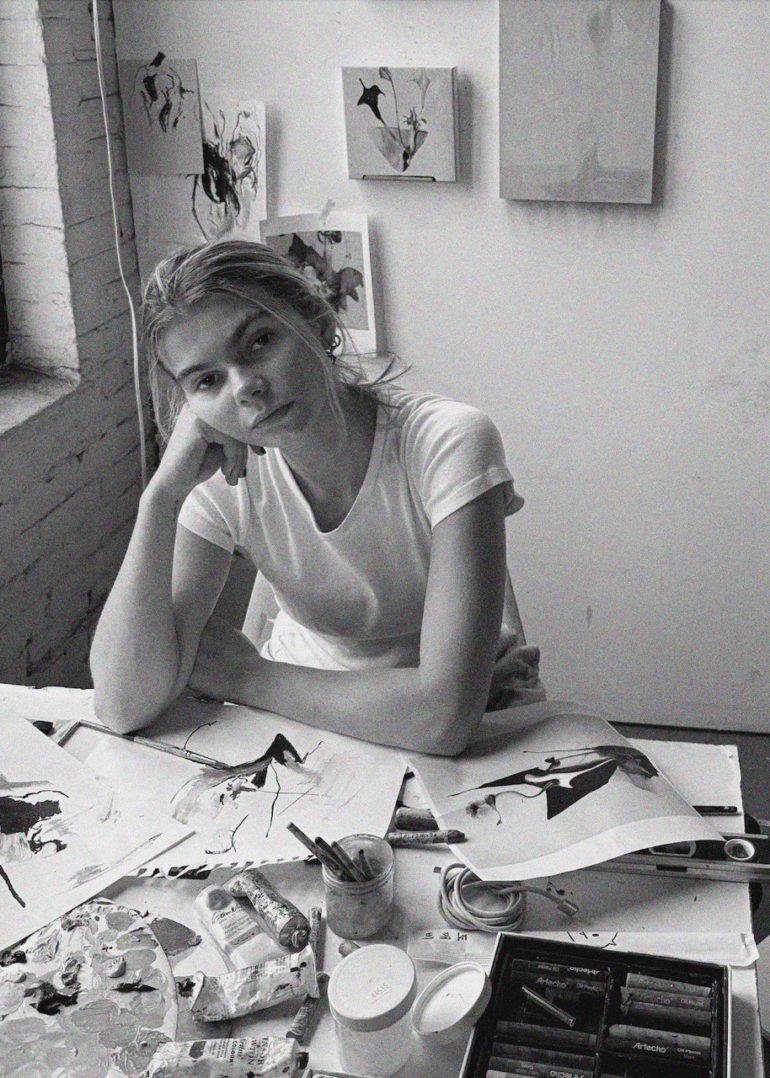

Currently featured in The Courtauld Institute’s East Wing Biennale: RE:VISION (until August 2027), London-born, New York-based artist Camilla Ridgers is known for her striking explorations of authorship, technology, and materiality.

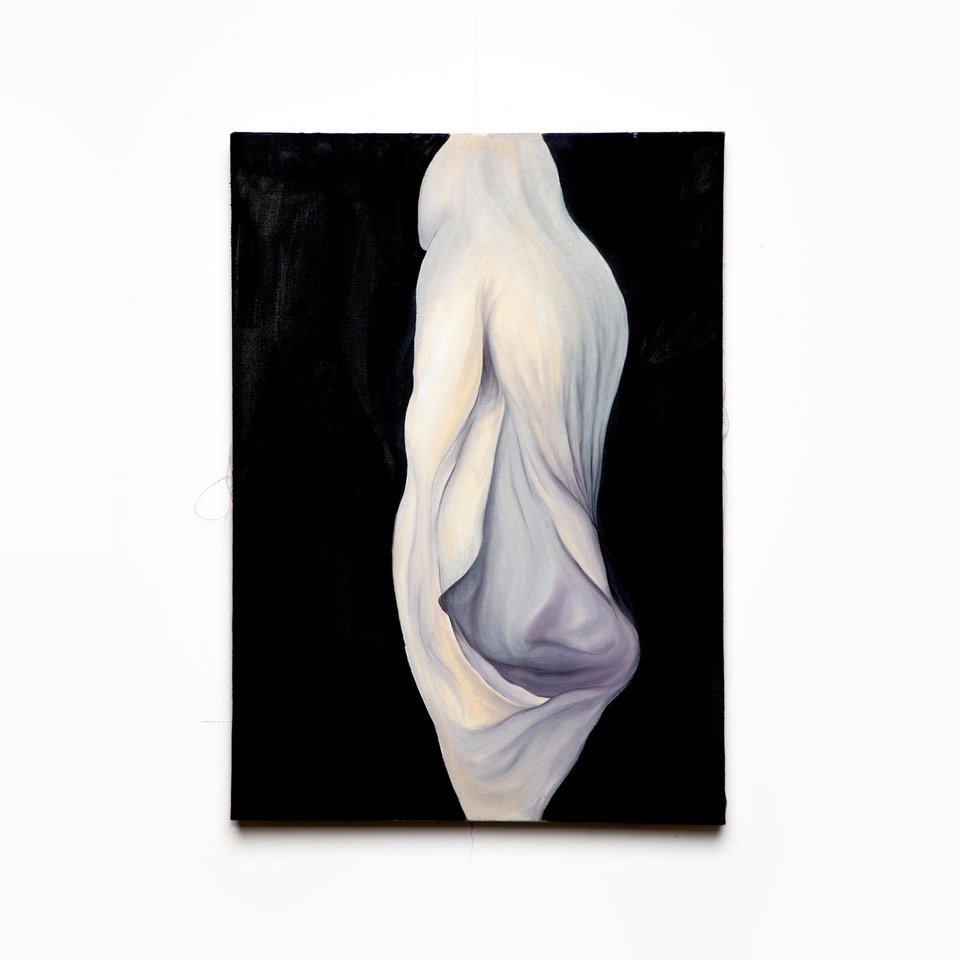

Her oil on linen work In Between Subjects II (2024) exemplifies her intermedia practice, which merges painting with generative computation to question the boundaries between human and machine creativity. A graduate of Central Saint Martins with a First in Fine Art & Creative Computing, Ridgers builds custom algorithms that reinterpret her personal archives–images, sketches, and objects–translating digital glitches into tactile painterly form.

Ahead of her participation in RE:VISION’s upcoming discussion series at The Courtauld this November, Ridgers speaks with Culturalee about shared authorship, the allure of error, and what it means to paint in the age of algorithms.

‘In Between Subjects II’ sits at a fascinating crossroads between human intuition and machine interpretation. Could you walk us through how this piece came to life, from your initial inputs to the algorithm’s role in shaping the final image on linen?

The work developed out of Pixel Pants, my first experiment with generative image-making.I fine-tuned a pre-trained GAN architecture on a small dataset I built myself, using photographs of underwear belonging to me, my mother, and my flatmate. It was a way of testing how the network would respond to unfamiliar data, imagery that fell outside its learned distribution. The algorithm struggled to make sense of them, returning these uncanny hybrid forms. That confusion became the point of interest: a way to expose how the machine perceives and misperceives the world.

In Between Subjects grew from that initial curiosity. I began to move away from the literalness of the garment and towards something more internal, exploring how identity, perception, and technology fold into one another. I built a new dataset from my own quick sketches of flowers, fabric folds, and bodies (recurring visual motifs in my practice) and trained the same model again. This time it could no longer find coherence. The results were spectral, genderless, almost mythological. They reminded me of the female Surrealists and their imagined hybrid beings that exist somewhere between human and non-human states.

That was the moment I realised the algorithm wasn’t just a tool but a kind of collaborator. Its inability to understand became productive a space for new compositions to emerge. Translating those outputs into oil on linen allowed me to slow the process down, to sit with the tension between recognition and refusal, and to transform a fragment of digital misreading into something tangible.

Your process often involves translating digital ‘errors’ or misreadings into painterly gestures. How do you decide which of these algorithmic glitches to preserve, and what draws you to transform them into physical form?

I get excited by images that sit on the edge of legibility, where form begins to take shape but never fully resolves. Re-rendering these fragments in oil shifts them from fleeting digital moments into something material and enduring. It’s a process that allows me to think with the system, finding meaning in the gaps of its perception.

I choose these unformed images because I find my subconscious impulse to make sense of the image and to anthropomorphise it an important part of the process. The projection of emotion and intent onto the machine’s neutrality creates the most interesting space; it’s where the work begins to exist in this latency I’m searching for!

The title In Between Subjects II suggests a space of negotiation, perhaps between artist and system, or between image and meaning. What does “in between” represent to you in the context of this work?

I first thought the work would be called co·a·lesce, because I was thinking about two parts coming together: intuition and system (human and the machine). But what fascinated me was the interstice the site between, rather than the result of coming together. That’s what “in between” means to me–it’s not a midpoint, it’s an active state of negotiation. I had already chosen the title when I came across Amelia Jones’s In Between Subjects it felt like finding language for something I’d already been circling. Her writing on the subject as something performed rather than fixed ‘a self that exists through relation’ resonated deeply with how I think about my paintings. The works I make also exist through relation:where identity and authorship are constantly re-formed through interaction. I’ve always been drawn to materials that behave this way blinds, frosted glass, bubble wrap things that reveal and conceal at once. So I think the “in between” isn’t something I try to depict; it’s the condition the work is made from

Generative technology introduces questions about authorship and agency. How do you personally navigate the balance between control and surrender when collaborating with algorithms?

Working with algorithms feels like navigating a rhythm that’s constantly shifting just when you think you’ve understood its logic, it changes. I set the parameters: the dataset, the structure, when to interrupt. But what happens inside that frame is unpredictable.

The algorithm brings its own form of cognition — non-conscious, pattern-based, impartial — which confronts the subjectivity of my own decision-making. I have to allow the algorithm to reveal its own logic, before I re-enter and interpret the outcome through drawing or paint. It’s not about letting the machine “make” the work, but about recognising where its partial vision exposes mine. The collaboration becomes less about authorship in the singular sense and more about a distributed form of seeing.

Your background spans fine art, creative computing, and fashion. How do these disciplines inform one another in your practice, and do you see your paintings as existing within, or outside of, traditional definitions of painting?

When I was studying Fine Art at Saint Martins, I was also working as a stylist on the side. Fashion has always been part of how I think visually it taught me about and how objects or materials hold identity. In In Between Subjects, fashion sits more quietly, but in other projects, like Pixel Pants, The World’s Longest Washing Line, or my CCTV High Heel, it’s super central. Those works use fashion objects underwear, clothing, heels to talk about visibility, exposure, and control.

Creative Computing came later, during Covid, and it changed how I think entirely. It opened up this fascination with data, bias, and perception….. how systems see, and how they fail to see. From that point on, I started thinking about images less as static objects and more as networks of decisions and assumptions. That sits underneath everything I make now.

I haven’t really thought about it much before, but I suppose my paintings are quite traditional in form they’re oil on linen. Still, they hold a digital logic beneath the surface. They begin as data and evolve through the physical act of painting. So while they belong to painting’s lineage, I hope they maybe can question where painting begins and ends.

You’ll soon be joining The Courtauld’s RE:VISION panel on authorship and materiality. In your view, how is the role of the artist evolving in the age of machine learning, and what excites or unsettles you most about this shift?

When I was writing my dissertation, I became interested in how authorship shifts when humans and machines create together. That research changed how I understand creativity; it isn’t a single, controlled act but something that unfolds through interaction. Csikszentmihalyi’s Systems Model helped me understand creativity as a networked process that depends on constant exchange between individual, field, and domain. Hayles’s writing on nonconscious cognition pushed this further, suggesting that both humans and machines make decisions beyond conscious awareness. Working with generative systems made these ideas tangible. Once you train a model, it doesn’t simply act independently it reflects and refracts the logic you’ve given it, producing outcomes that reveal as much about the system’s structure as they do about your own. The unpredictability isn’t just a loss of control but a point of discovery, where authorship is no longer fixed but continually redefined through exchange.

For me, the artist’s role has always been to expose systems: to make the unseen visible, to make the unknown known. That hasn’t changed, but the systems we’re confronting have. They’ve become invisible, embedded in datasets, algorithms, and corporate infrastructures. Machine learning hides bias behind the illusion of neutrality. Large-scale datasets reproduce old hierarchies of gender, race, and class and deepfakes blur our sense of what’s authentic. AI doesn’t just reflect culture; it amplifies its distortions.

That’s what unsettles me most: the speed at which these technologies are aestheticised before they’re understood. They’re presented as progress, but often without reflection on whose perspectives are being encoded, or erased. When I build my own small datasets, I do it to stay close to that question: to understand what is being learned, misread, or left out. It’s a way of reclaiming agency within a system that thrives on scale and opacity.

What excites me, though, is that artists can now work from inside these structures. I think artists are uniquely equipped to navigate that discomfort. And that’s where painting feels essential again. It slows everything down. It reintroduces time, touch, and subjectivity. It’s a way to make the human visible again inside something built to erase it.

Find more information on RE:VISION here.

Find more information on Camilla Ridgers here.

All images courtesy of Camilla Ridgers.