By Frances Forbes-Carbines

The new Nordic noir: works on paper from Edvard Munch to Mamma Andersson exhibition at the British Museum is curated in such a way that it really feels like being in a forest. Artworks emerge through the darkness in low lighting: the interior walls are painted a verdant pine green and the works are often of a nature theme – a drawing of an ancient and gnarly Norwegian spruce here; an extraordinary watercolour made using glacial meltwater to highlight the effects of global warming by Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson (b. 1967) there. Lost in the woods, you walk about in a state of enchantment, feeling yourself to be thousands of miles from the bustling Bedford Square just outside.

Room 90 of the British Museum, a cavernous room right at the back of the museum, is somewhat hidden from view: you have to mount the circular stone staircase of the Great Court, take a left, more stairs to the fourth floor, pass through a recreation of an Egyptian mausoleum and then more stairs. Up so high, you lose the crowds of the lower levels: people up on the fourth floor view the pictures in reverential silence.

How did the exhibition come about? “This project was a five-year voyage of discovery,” curator Jennifer Ramkalawon said in a statement. “These countries have so much creativity to offer with contemporary artists exploring themes of nature, the environment, identity and heritage. The artists in the show are well-known in their home countries, but this exhibition aims to showcase the incredible array of talent from the Nordic lands to a wider UK and international audience – many of them are on display for the first time.”

The landmark collecting project, explains the British Museum in a statement, is supported by a substantial grant from charitable organisation AKO Foundation, which resulted in the acquisition by the British Museum of almost 400 works by artists from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. It has added to the many Nordic prints purchased by the Museum in the 1990s.

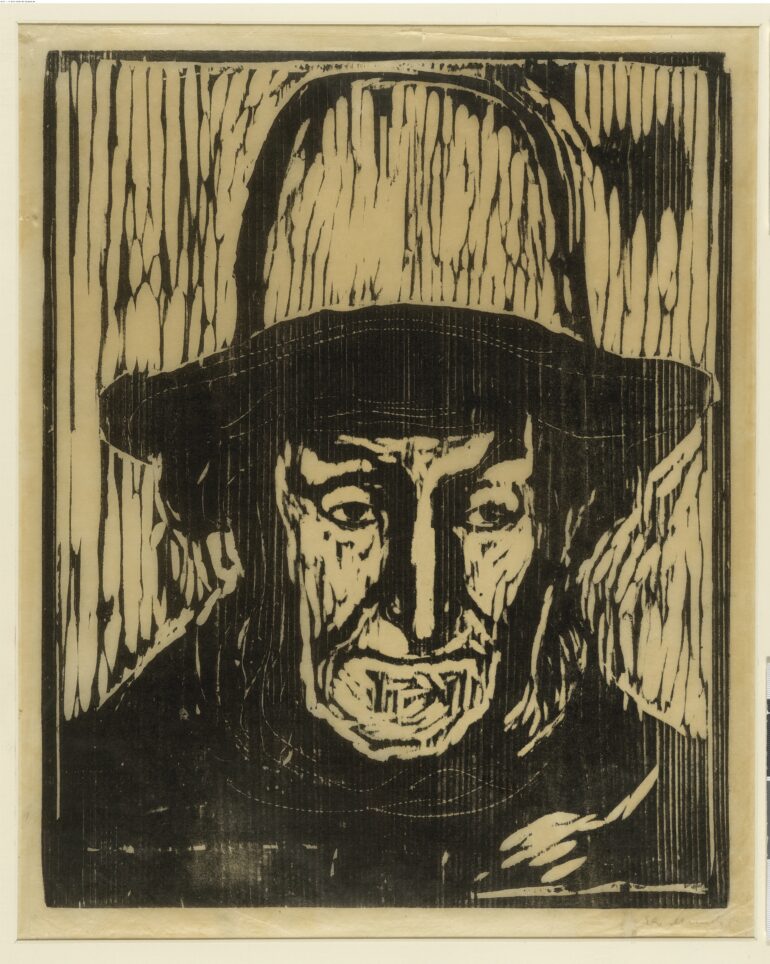

The exhibition begins with a work by Edvard Munch (1863-1944): The Old Fisherman (1897) – somewhat bleak in its starkness, it is followed closely by Munch’s Melancholy III (Melankoli III) of 1902, a colour woodcut depicting Norwegian writer and critic Jappe Nilssen, who spent years unhappily in unrequited love with one Oda Krogh – she was married; she is in the background with her husband while Nilssen broods in the foreground, chin on hand by the shore. This is a dark work, uncompromising in its sadness, as is The Old Fisherman – the latter being referred to in the catalogue as depicting a ‘lugubrious fisherman’ with a ‘dour visage,’ wearing a large sou’wester. It is an exhibition of Nordic Noir, after all, and these austere woodcuts set the tone faithfully.

Munch directly inspired the artist who follows in the exhibition: Rolf Nesch (1893-1975): the information plaque tells us that Nesch emigrated to Norway from Germany to escape the Nazis, and that he had visited Munch in the 1930s and learned from his printmaking techniques. Nesch’s works here are colourful, but admittedly the overarching theme of the exhibition seems to be dark hues: as participating artist Jeff Olson (born 1981, Swedish) is quoted in the catalogue as saying, “I am interested in the ambivalence that the night offers. Darkness can bring danger and discomfort but there is also a kind of poetic potential in the interdeterminacy.”

I asked Ramkalawon about whether she had travelled widely in Scandinavia to make the exhibition: she replied that she had the opportunity to meet many of the artists featured, but that many were not available during the summer months because that is when they visit the tiny islands around Sweden and Norway in order to take in as much sunlight as possible before the long Scandinavian winters.

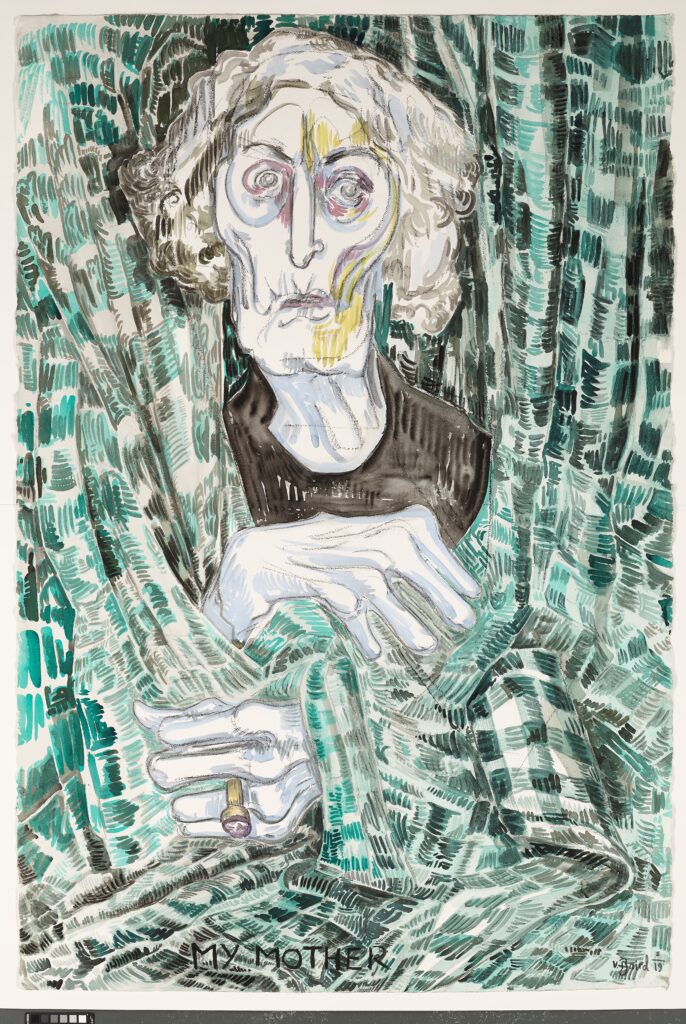

The words of artist Vanessa Baird, leading contemporary Norwegian artist born in Oslo, make for a startling and arresting corner of the exhibition. They are certainly very intense. One of them speaks about the difficulties in looking after a relative and the claustrophobic feeling that this can evoke, with the mundane tasks of the everyday mixed with the consequential rows between family members. Baird’s painting “My Mother” (2019), watercolour on paper, gives the viewer cause to do a double-take, displayed in the far corner of the exhibition, the mother figure stares through the viewer with huge, owl-like eyes. Baird received the prestigious Lorck Schive Art Award, Norway’s equivalent of the Turner Prize and it is clear that her works resonate with a sizeable and growing international audience.

A section of Nordic Noir is devoted to the art of the Sámi, the indigenous people who inhabit the area that encompasses northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia, and who have traditionally lived by herding reindeer and fishing. The catalogue notes how the Sámi were exploited by the Swedish authorities in the seventeenth century: their religion was outlawed in 1685; their sacred Sámi drums burnt and their religious sites desecrated. In Victorian times Sámi were denigrated by governments and were viewed as ‘backward’: they were made to speak the Scandinavian languages through a process of forced assimilation. I was incredibly moved by the work of Sámi artist Britta Marakatt-Labba (born 1951), a Swedish Sámi textile artist and printmaker: the work is called Garjját (The Crows) and shows the brutal break-up of the protest against the damming of the Alta River in 1978 – a flock of crows sweep down and transform into policemen.

To leave the exhibition was to emerge, blinking, from the dark forest back into the daylight of Montague Place, but the sense of wonder evoked by the artworks stays with you.

Nordic noir: works on paper from Edvard Munch to Mamma Andersson is a free exhibition and opens in Room 90 of the British Museum from 9 October 2025 – 22 March 2026.