Is Ian Brennan a young contendor for the Crown of the late great artist Lucian Freud? In this candid and compelling interview, Culturalee sits down with the Irish artist whose raw, emotionally charged work has drawn comparisons to some of the greats of contemporary figurative painting. Brennan opens up about discovering his artistic voice later in life–decades after it was quietly silenced during his school years in Ireland.

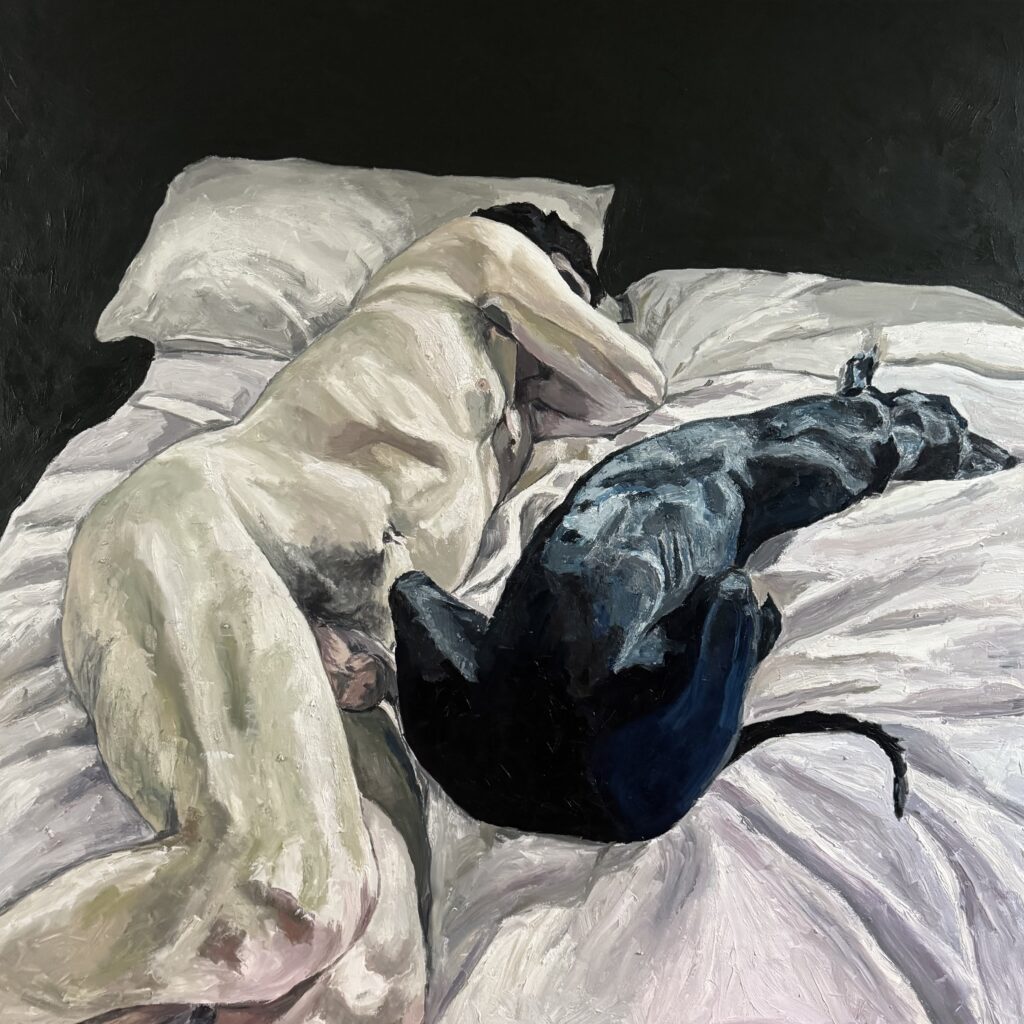

He shares how pivotal encounters with Tracey Emin and a private visit to Lucian Freud’s studio helped ignite his creative journey, and why artists like Emin, Freud and Jenny Saville continue to influence him. Describing himself as a “psycho-figurative” or “psycho-abstract” painter, Brennan explores how his background as a therapist, and the unique experience of being a twin, deeply shape the psychological depth and intensity of his work.

This is more than a conversation about art—it’s a story of reclaiming identity, finding courage in vulnerability, and embracing the power of late blooming.

Let’s start at the beginning. Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you first became drawn to painting?

Sure, I was born in Co. Limerick in 1983 and grew up only 10 minutes away from one of Ireland’s most famous exports–The Cranberries.

Art was not encouraged as a career in Ireland in the 80s and 90s, and to be honest it is still discouraged. There comes such fear and judgement towards the arts, despite Irish people being so artistically rich. Be it music, writing, acting, visual arts etc. In a weird way, you have to “make it” outside of Ireland to be considered a successful artist (and I have done just this).

In primary school I remember drawing with big thick crayons for the first time. I was mesmerised by such phallic objects! I have memories of drawing circles with different colours, almost Kandinsky like when I look back. I loved scraping the crayons with my fingernails once I had laid down the colours on the paper, and then picking the shavings from under my nails for hours. I loved how they smelled, the waxy sensation and can even remember trying to eat them!

In secondary school everyone wanted to do art, so the principal put all the names of the students into a hat and unfortunately my name was not pulled out. I parked my dreams aside and pursued a studious six years in school.

I worked in corporate for seventeen years. In my late 20s I trained as a psychotherapist and this changed my life. In a way this is exactly how I came to art. I suppressed my creativity for so long that I had a breakdown – or a breakthrough, if you will. At thirty-five I took six months off work to give myself space. It was the best gift I ever gave myself. I bought myself a canvas and some oil paints towards the end of the 6 months and the rest is history.

People are often shocked when I tell them that I only started painting seven years ago. I hid the fact that I could paint from just about everyone–including myself.

Who or what are some of your biggest inspirations, whether artists, places, or life experiences?

My biggest inspiration is the relationship. Be it my relationship with myself, a lover, nature, sex. Ultimately I let these experiences make the work. I’m informed by my life experiences and relationships.

I have a twin sister and was cocooned in a relationship at the very point of conception. I only know relationship. I only exist in the world in this way. It’s a bit mind blowing when I really think about it.

I find it difficult to navigate the world unless I look at it in terms of a relationship. Even the act of this interview is a relationship. The person reading it is now in a relationship of sorts with both you and I. And this is always how I paint. I want the piece to be as real and as raw as possible.

In terms of artists who inspire me, I’m heavily influenced by Lucian Freud, Tracey Emin and Jenny Saville.

It’s kind of a bit mad that Lucian’s Grandfather was Sigmund Freud, and that I trained as a therapist and now my work is compared to Lucian. Last year, his assistant of twenty years and now artist in his own right, David Dawson invited me to Freud’s studio, which is not open to the public. I got to walk barefoot on the floors he painted from and see his trolley and brushes and the wrought iron bed that people lay on. It was a real pinch me moment.

Dame Tracey Emin is the other artist who influences my work. And when I say influences, it goes a bit deeper. She changed my life. I applied for her art residency in Margate about two years ago and she invited me to meet her face to face at her studio. I got an hour of Emin’s time and critique. She told me that out of the thousands of applicants I was the only artist at the interview who was self-taught.

Saville’s scale of work and perspectives really gave me the permission to make the work that I make now. She allowed me to make mistakes in the work and know that this was the work itself.

How would you describe your style of painting? Has it evolved significantly over time?

I would describe my style of painting as psycho-figurative or psycho-abstract. I don’t always have words to describe my “style” per se, and I try not to make my work from a cognitive place so I guess I would say it’s a somatic surrendering of sorts.

It’s pure. It’s raw. I let the brush and the paint and the canvas do the work. I simply surrender to the energy. Another relationship emerges here – a triad between 3 inanimate things that make something come to life. It’s a magical thing, painting.

My process has indeed evolved significantly over time. If you look at it in terms of “the relationship” I can certainly say that my relationship with myself has evolved over time too.

When I first started painting I was making work to please people. I wanted people to like my work, which I translated into them liking me.

So when I say that my relationship has changed with myself, I mean I no longer care if people like me or not. I also don’t care if people don’t like my work. In a weird way I actually kind of like it when someone doesn’t like my work.

My work has evolved in terms of the aesthetic too. My canvases are bigger, I use so many more layers of paint and I allow myself the privilege of making mistakes. Each of my pieces can take months to make. In the beginning I was too impatient to make the pieces that I make now. I wanted instant gratification. It’s a slow process my work.

There’s often a strong emotional or psychological depth in your work—is that something you’re consciously aiming for, or does it emerge organically through your process?

I have quite a complex process. I believe I am one of the only artists in the world who engages in such an intimate way with the sitter.

Because I paint the relationship, I’m ultimately inviting the sitter into the most intense of relationships for a period of approx. 3-4 hours. I give myself to the sitter and the sitter gives themselves to me.

I facilitate a somatic meditation to begin with.

This involves breathing into almost every part of our bodies. I do it and the sitter does it. We feel things in our bodies that we were not aware of before. At this point we are deep in the “relationship”. I explain to the sitter that I will pick up on certain feelings or energies in their body. I don’t label this, I just feel the feeling. I might feel a kick in my stomach, or a punch in my chest, or a sadness in my thighs or a numbness in my toes. There is no wrong way to be. I just ask that the sitter is authentic.

After the meditation I invite the sitter into a “witnessing” exercise. We look into each other’s eye’s for no specified amount of time. There are no words spoken. Both the sitter and I can stop this when we feel that the dosage is too much.

This is probably the most important part of my work. Even though no words are spoken and we are in complete silence sitting pretty close to each other, it’s the loudest conversation that you will have with another person.

I often shed tears during the witnessing sessions. With the permission of the sitter I can pick up on stories, traumas and feelings. Even though we are both clothed during this we are also very naked and vulnerable.

I allow myself to be seen and the sitter does the same. The work is co-created. I am in control of me and the sitter in charge of themselves. There is no power imbalance and I’m equally vulnerable, or as I like to say, equally human. I cannot make the work without the sitter and their willingness to engage and surrender into the unknown.

After the witnessing session ends the sitter then removes their clothing. We work with what has just emerged in the session. It’s the single most intense feeling of feeling alive I ever feel during this part of the work. We have just spent a significant amount of time revealing ourselves to each other.

The container of trust and vulnerability has been constructed at this stage. I’m holding literally everything and nothing at the same time. I have to continue to surrender to the organic way of the work.

I then ask that the sitter moves or shouts or does whatever it is that they need to do so that they can be in the moment. I work with photos from this point. A dance emerges during this part of the sitting. Feelings can be very intense, even erotic. There is a crescendo of sorts taking place. I might take over 200 photos.

It feels like I’m writing about having sex when I describe the process. In a way it’s more than that. When people have sex there rarely exists desire. When I work in this way desire can be at it’s most potent. The energy can be so intense that I’m depleted at the end of a sitting.

I give my sitters a mental health warning before we engage in the work. I trained a psychotherapist (don’t practice as one) in my late 20s and I bring certain learnings into the sittings. I also spent some time in Buddhist retreat centres taking courses on Intensive Deep Listening, that’s where I learned to hold eye contact.

When I paint the painting itself, I can access the feelings that arose during the sitting and I bring these feelings into the work. It’s the ejaculate of the sitting coming to life. I’m birthing a relationship. I’m birthing a piece of art.

You’ve taken part in exhibitions that carry strong social messages, like Fragile at the Bomb Factory, which raises awareness of war and conflict. How important is it for you to use your work to engage with issues like these?

I live in a world that has never before been so unstable for someone of my generation. Never before has the world been on the brink of a war so close to my doorstep.

Fragile was in important exhibition for me to take part in. Most of the world leaders are men (toxic men) and it was important for me to show that man can be vulnerable and soft and fragile.

It was taught to me as a young boy to “be strong” and “don’t cry”. These are unconscious messages that have been passed on to boys from previous generations. I don’t know a period in time when it was ok for men to be “fragile”.

Men are taught to be the bread-winners in families, taught to fight, to be physically strong. What it is to be man in the world is so much more than being strong. It’s important that we reclaim our vulnerability and show others that it’s ok to cry, to be open.

I believe that my work has a domino affect on people wishing to be wholeheartedly themselves. We can’t just live in our shadow parts of anger, rage, resentment, defence. We must dip into the other parts of the human psyche and feel all our feelings. Imagine having the pressure of needing to be strong all the time? It’s exhausting. I encourage others to look at the softer sider of themselves through my art. My work is confronting in this aspect.

You also recently donated a piece to the Pink Noise charity auction at MOCO Museum in support of mental health. What role do you think artists can play in supporting causes like this, and why was this particular one meaningful to you?

Mental health is right up there in terms of looking after myself. It’s like a muscle, if you don’t actively use it, you lose it. Having rained as a psychotherapist and been in therapy for more than 12 years I can’t tell you how valuable it has been to me to seek support.

In fact I wouldn’t have come to be an artist without being in therapy. It wasn’t just talk therapy I availed of. I worked through a somatic lens too. I put this down to unblocking the artist within. Conscious movement has been a gamechanger for me being able to access my creative part. When we shut down our emotions we also shut down our bodies and we become contracted. Dance and talk therapy were pivotal to my being able to make art.

Are there any particular exhibitions or works that you’re especially proud of? For example, you recently exhibited at the Irish Academy of Art Summer Exhibition–how was that experience?

I did recently exhibit at the Royal Hiberian Academy of Arts in Dublin for their summer show. I remember when I first started out painting it was the number one show I wanted to be part of in Ireland.

However for me, my proudest moment was showing my works along side Salvador Dali, David Hockney, Auguste Rodin and Andy Warhol at the Male Form auction with Bonhams in Brussels last year. I never imagined my name being up there with artists who I saw at major exhibitions or read about in books. It was a real pinch me moment. When one of my pieces sold for €25K it was even more of a pinch me moment.

I’m also particularly proud of my £1 million painting of Sue Tilley which I was fortunate enough to exhibit at Saatchi Gallery in London 2 years ago. I am a big fan of Lucian Freud’s work and to have the world’s most famous muse agree to sit for me was something I never thought possible. When it sells I’m gifting the full amount of money to Sue to sit nude for me for one last time in the history of art.

How do you choose which exhibitions or collaborative projects to take part in? Is there a common thread that connects them for you?

As an emerging artist, who I work with is important. When Daniel Lismore invited me to collaborate at Fragile last year it was a no-brainer for me. I have the utmost of respect for Daniel as an artist, as an activist and now I’m lucky to call him my friend. Being invited to show as MOCO in London for Pride month was also important. My work, though confronting and often shocking, does not shy away from expressing who I am as a human (in all my parts).

I don’t have gallery representation, or an agent or a manager, I do all this myself. I’m an independent artist.

What does your studio practice look like day-to-day? Do you follow a structured routine or a more intuitive flow?

I work intuitively, however when I have a deadline or a private commission that can be good to keep me motivated. Being an artist is a lonely vocation. You don’t have colleagues, you don’t have a steady income so you really need to be kind to yourself as nobody else will be that person.

I often work late into the night, sometimes I’ll start around 8pm and could find myself going to be at 5am. It depends. When I was in Margate in would start early in the morning and come home and go to bed about 8pm.

I’m back working from my studio in the farmhouse in Co. Cork. It’s where I started so it’s nice to be with myself in isolation again. The work flows differently in this setting. I don’t really socialise or go out. I am my own greatest tool and it’s important for me to go back inside myself and see what needs to come out.

I love being able to look up at the stars in the countryside, with no light or noise pollution. I talk to them. I talk to my ancestors and I ask them for help. These conversations are potent

This is how I work. My work is autobiographical in this sense as I’m painting what’s going on inside me.

What’s next for you? Are there any upcoming exhibitions or projects you’re excited about?

I’m currently working on a piece that will be unveiled in Feb of next year in the UK at an exciting event. It’s different to the works I’ve created in the past as it’s not as heavy emotionally. Each piece can take me 3 months to make so I’m limited with how many works I can create in a year. It’s important that what I’m painting is authentic, just like the relationship.

I’m open to gallery representation and other collaborations for sure. I’m at the stage where I just want to paint in my studio and let someone else worry about placing my works. The art market is changing and I believe artists are reclaiming their power. We need to support each other.

Finally, what advice would you give to emerging artists navigating the balance between staying true to their voice and engaging with the wider art world?

I would say to any emerging artist to ask yourself what it is you want from your art. Do you want fame? Do you want money? Do you want to make powerful art?

There is no wrong answer. Once you are clear in your motivation just go for it. There are no rules in the artworld. You are the creator of your own destiny. I would also say what Dame Tracey Emin once said to me: “work very hard!”

Find out more about IAN BRENNAN here: https://www.ianbrennanart.com