Sculpted Dreamscapes: Rob Mango’s dimensional paintings exploring the unconscious

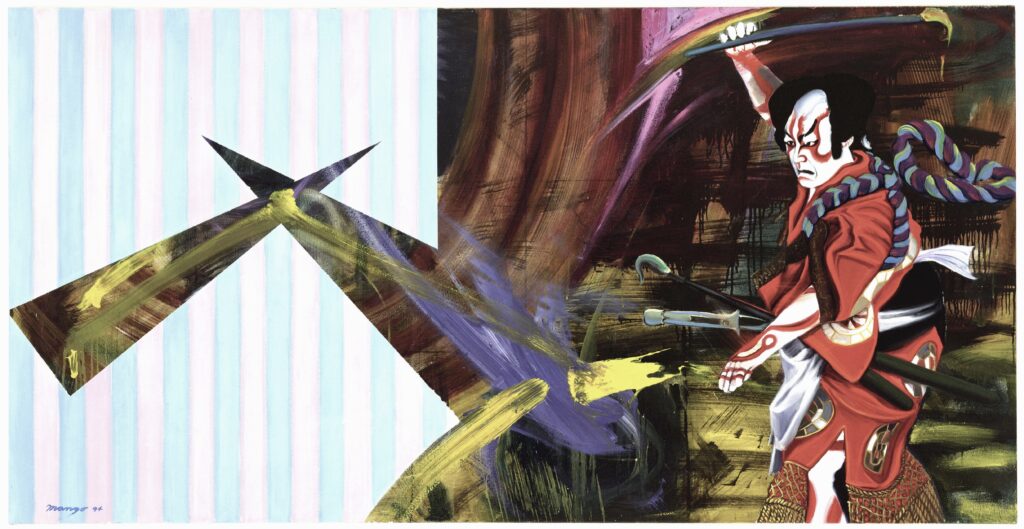

For the latest in our series of conversations with artists and creators around the world, Culturalee speaks to Rob Mango. Rob Mango is a New York–based artist whose work, spanning from the 1970s to today, investigates modern mythology and traces the evolving currents of contemporary culture. Known for his dynamic sculpted paintings, Mango expands the possibilities of the canvas.

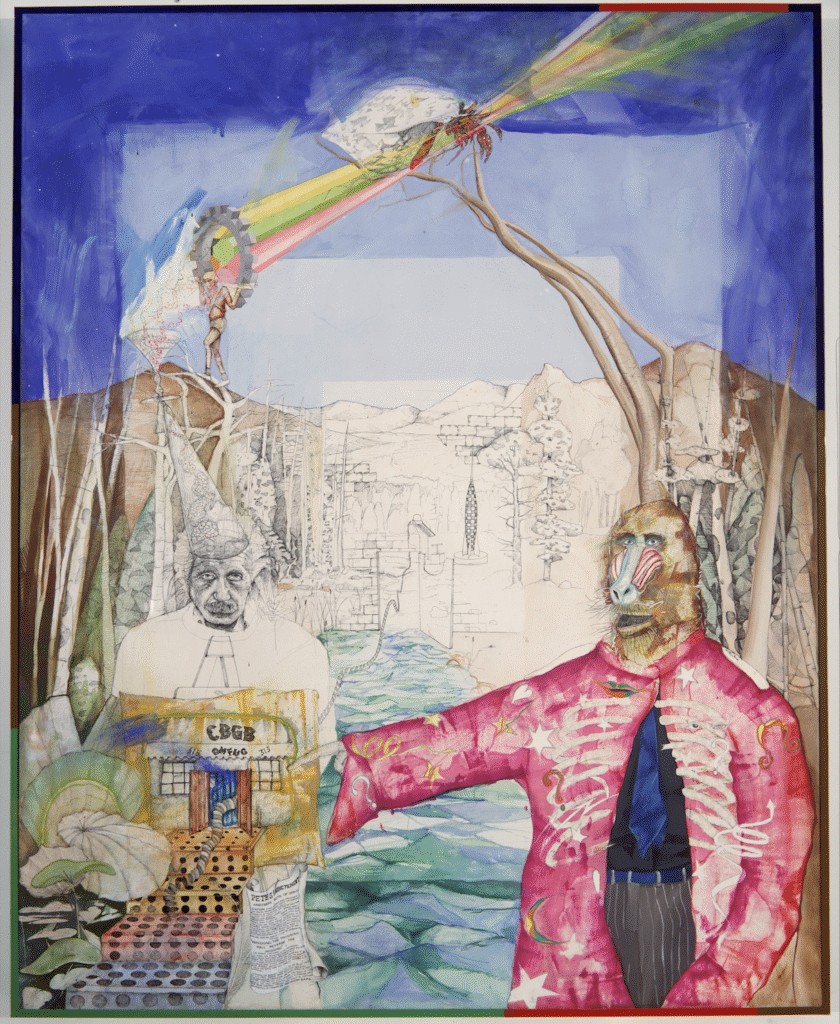

Mango weaves together movement, symbology, and color in pieces shaped by his formative years in New York’s vibrant 1970s art scene. In 1984, he founded Neo Persona Gallery in TriBeCa, driven by a vision to help transform the neighborhood into a thriving creative center.

You were an integral part of the 1980s Tribeca art scene, founding the Neo Persona Gallery, a space that drew icons like Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan. How did that moment in New York’s cultural history shape your artistic voice, and what did it mean to both create and curate in such a transformative era?

In the art scene of early 1980s New York City, each neighborhood had its own unique art chemistry. Soho had cornered the commercial aspect of the business. Trying to penetrate the galleries was a door-slamming experience. My ground-floor studio on Duane Street embodied the more maverick ethos of the Tribeca artist crowd – the raw pulse of unfettered expression fueled by the naked honesty of existential unfolding. Weather permitting, my door was open. With the loading docks working all night, it was an almost 24/7 revolving door of eccentric, interesting people, from other artists to celebrities and New York culture makers. The scene was fluid. Open. Unguarded. Devoid of the artifice that the Soho brand-making machine needed artists to buy into.

Many artists, including myself, weren’t able to crack the code of Soho’s art gatekeepers. Before Tribeca had its name, lawyers and finance people who wanted to be around the artistic vibe had begun to move into the neighborhood. Raw lofts were transformed into architectural digest-style gems and offered to the professional crowd. The clash of gentrification and non-conformist creative mindset escalated with the drama of an episodic television show. I knew so many sensational artists at that time and felt in my gut there was an audience hungry for what we offered; that we could launch ourselves.

The creative process isn’t something “done” inside prescribed guardrails. It’s a search that happens simultaneously in all directions, including backward and forward in time. That’s what New York icons like Marty Scorsese and Bob Dylan related to when they found their way to my door in those early years. As did Norman H. Segal, a building owner/developer. Though recognized for his civic improvements, his true love was the arts. He became a friend, mentor and collector. Once he understood the difficulties of existing outside the consecrated realm of the Soho Gallery scene, it was one small step to partnering with me to open Neo Persona Gallery in 1984.

What it takes to run the business side of art isn’t so different from what’s needed to create it: curiosity, drive, insight into what makes people tick, and a talent for synthesizing disparate elements into something cohesive.

Your sculptural paintings push beyond the traditional boundaries of canvas, merging painting and sculpture into a single dimensional form. What first inspired you to incorporate physical depth into your work, and how has this expanded your exploration of movement, symbolism, and light?

My inborn talent was enabled by the penetrating exploration of philosophy and language instilled by my mom, an early and exacting classical training at The Art Institute of Chicago, as well as working summers executing engineering drawings of products for my dad, and my developing path/process of pulling all the schools of art and thought into my inner crucible. Both the body of my painted works and the late 1970s and early 1980s 3-D works were the result. The catalyst for the new form was a crushing blow to my psyche that extinguished the known path. The epitome of the ‘dark night of the soul.’ Sometimes we have to be broken by life for a new light to find its way through the cracks into our deepest recesses.

When creative output is driven by a constantly regenerating quest for your origins, staying in a defined “lane” becomes impossible. I did finally get my Soho solo exhibition at a gallery, and they were selling my work. I kept up with their demand to produce my popular “Mango nudes” for two years. They were uninterested in my other veins of expression. A chance conversation with a collector who asked about a series of New York City paintings he’d been hearing about but which weren’t being exhibited resulted in a falling out with the gallery. My paintings were returned unceremoniously to my loft.

They sat like shrouded figures at a funeral on my studio floor, an homage to the death of my artistic career. I spiraled into depression and flirted with the dissolution that many storied artists lived their whole lives in. After passing by them like an amnesiac stranger for weeks, I unwrapped them, hoping a visit with old friends might leverage me out of my mental and emotional morass. Instead, all I saw was a pastiche of color and abstracted form that seemed neither to offer nor to evince any meaning. In a spontaneous existential outburst, I pierced the flesh of the closest canvas with the box cutter in my hand. In a feral act of catharsis, I dismembered all the canvases with surgical precision.

For days, the severed canvas sections of anatomy lay in a chaotic jumble where they’d fallen. One morning, I found myself plucking all the pieces of a male nude from the detritus. By the light slanting in the window, I turned them this way and that, seeing them as individual units that could, perhaps in some new and interesting way, be reunited. The fragmented paintings still possessed an animus and the potential for an afterlife.

The vision for 2-D paintings with 3-D sculpted foam elements emerged from the cracked earth of my psyche. Because what leads me on, and often saves me, is that I’m an inventor. An inventor doesn’t repeat, because repeating creates a system. The emotion of the period was a powerful force that didn’t give a damn about the outcome. Once again, the quest was all.

You’ve spoken about your classical foundation , proportion, chiaroscuro, and draftsmanship and how it coexists with the freewheeling improvisation of artists like Duchamp, Rauschenberg, and the Surrealists. How do these seemingly opposite influences converge in your practice, and what kind of dialogue do they create in your studio?

It’s not so much a dialogue about or between influences, which suggests a point of view that looks through a lens of style. I’ve never approached art that way. It’s always an exploration of who I am, what I was, and what I will be. Disparate elements of a classical training, Dadaist and Surrealist inspirations, Freud, Nietzsche, and even the raw stream of consciousness of the Beat poets—all a total alchemistic education. A kind of primordial soup where thoughts and substances act and react to inflict visions on my mind without any stated “goal.”

This cumulative ocean of currents transmutes intellect from the rational to the ephemeral, and the result organically presents itself in a theatrical fashion that poses existential queries as much as it offers any reasoned “meaning.” A wholly other dialogue emerges when the audience is carried into the world of the piece on the wave of the questions it poses. The lines are blurred. It’s a two-way mirror, a bio-feedback loop.

Much of your work channels the unconscious images that surface in the liminal space between dreaming and waking. How do you access that creative realm, and what role does ritual or routine, like your early morning runs, play in bringing that dream imagery to life on canvas?

Epic nightly runs through dark downtown streets put me viscerally in an atmosphere that becomes dreamlike, divested of the polite social veneer daylight confers, and directly connects me to dual streams of the subconscious and the unvarnished sensory input of the world. Moving at competition-level speed for sustained distances through a landscape that echoes the shadowy sides of the psyche puts me in an oxygen-deprived, altered state, lately sought by many through the popularized practice of “breathwork.” I came to it organically over five decades ago, through the hardcore training experiences my track aspirations required.

Soaring through space at street level parallels internal mental flight. The degree of energy and qualitative mental acuity generated catapults me into the peak flow state I have to be in for authentic creation, where “normal” human mechanisms of logical thought and willful decision-making fall away, taking with them the mental static that stands in the way of being a pure conduit for inspiration.

At any point of conception in developing a painting, I fix the current image in my mind and set out on a blistering run, during which it changes and evolves in complex detail due to the oxygen debt that carries up a rich, inspirational infusion from the subconscious. My mind’s eye functions like a computer screen where I move around paint passages, insert and delete objects, deconstruct, and reconstruct…until I return to the studio, where I go to work, bringing those ideas into painted form.

I ingest everything I see and feel and smell along my route to nourish and augment the evolving vision: light, structure, architectural detail, and mood. The fantasy and reality of New York City becomes source material. It’s like in a Fellini movie in which you see everything in his frame. You choose a moment, allow all the elements to present themselves, and shape the composition into a consumable piece of art.

You’ve said that the “irrational and the symbolic can be more revealing than the literal.” How do surrealist ideas, from Duchamp to the Beats, continue to shape the way you construct your visual language, and how do you decide when a work feels “inevitable,” even if its meaning remains elusive?

The irrational is what isn’t circumvented by or supported by logic in the idea stream or in the act of communication. If you welcome the unconscious, if it’s something you seek and recognize, and it’s going to appear more. A thing is contextualized into a symbol. It’s not a symbol on its own. The creation of art is the application of intellectual functioning on unconscious debris. You’re making something in the physical world, attempting to reveal the ephemeral world. The elusiveness of this is a very engaging force. It’s what gets me out of bed every day.

The evidence, the refinement of technique, is to show the pathway from unconscious to conscious. What’s there? Meaning, beauty, transcendence. Thousands of choice points occur between eye, hand and mind. I create a lot of drawings before I launch to establish a central image or pose. I know that’s how I’m going to pry the lid off. But I haven’t set the background. The background is completely ephemeral; more like cooking than thinking. More akin to my mental process, which is movement, out of the known space, because you’re searching. For something to become, a place to go.

The vision of the rest of the painting starts to evolve around the image. I put myself in the cage of the painting and slice and dice so the audience can find entry points into the experience and share something, search with me. I don’t put myself above the viewer. I want to share with them in the highest, most tasteful, genius capacity I have. This loving of the audience gains trust and provides a license to something they couldn’t or didn’t conceive or experience on their own.

I’m not dragging a brand to my grave with me. I want to transcend style by having a level of competency that makes me different on this day than I ever was before. Meaning is always elusive because it’s a pursuit, not a destination. It’s like a rock sitting in space. The only way you can see all its facets is by moving around it. And the way you move around it is a pastiche of insanity, rationality, the pursuit of pleasure, putting yourself in the mind and heart of figures from different eras, things utterly foreign to the mind of modern man.

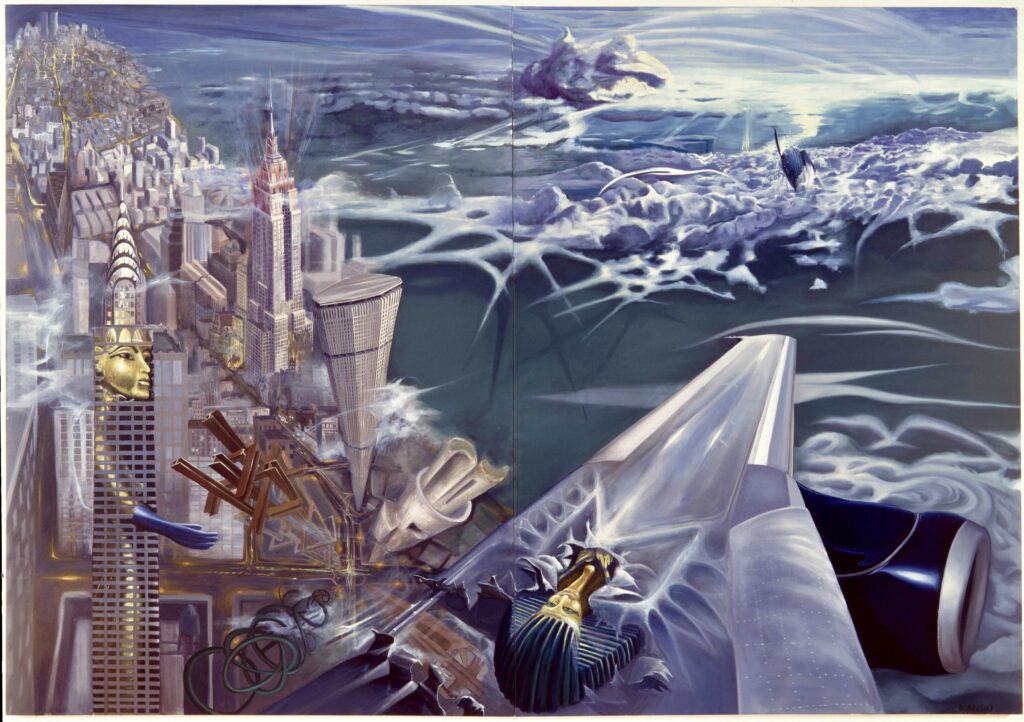

Like when a pharaoh is reincarnating. Where is he going? What’s on the other side of that tomb wall? It may be that the human mind is too limited to find that elusive meaning. It’s an eternal quest for my origins. I’ll never “get there.’”

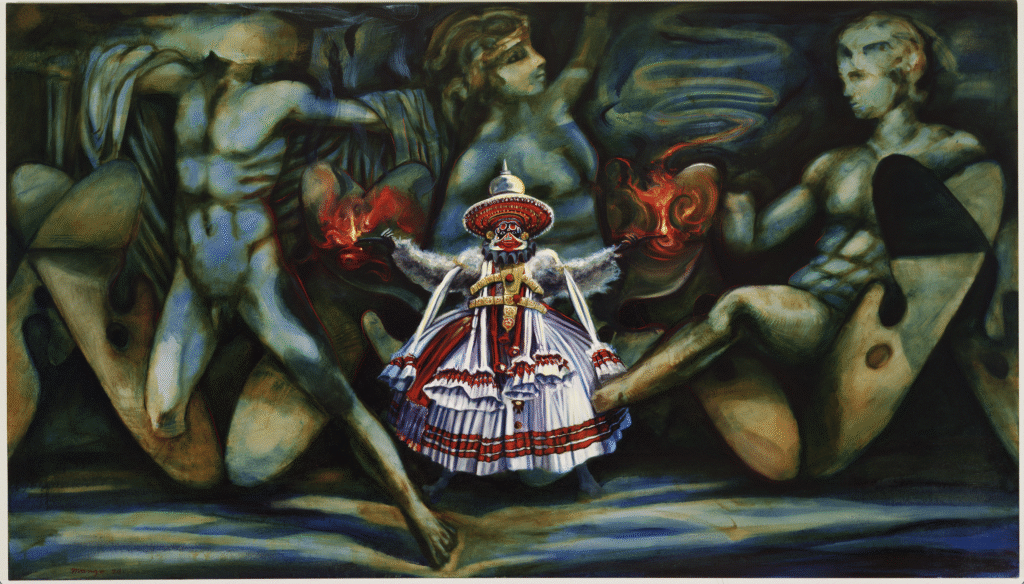

Your art often fuses mythological figures with urban allegories, Jesters, Shamans, and Gods appearing amid the pulse of the modern city. What compels you to revisit these archetypes, and how do they speak to the ongoing conversation between the human spirit, the unconscious, and the contemporary world?

Self Portrait with Hercules is a good corollary: there’s no light in the cave if the artist doesn’t illuminate it. Traveling through the archetypes of gods, shamans, and avatars—trying on their costumes—is to inhabit alternate realities, find what resonates, and eventually synthesize a personal philosopher’s stone distilled from bits of all of them. Like King Tut in Millennium. He’s the ultimate time traveler. And the airplane is the symbol of movement from past, to present, to future, illustrating a vortex of time and space so you have a view in both directions.

The gestation and birthing of these mythological works is my way of inhabiting these entities. The psyche is both ancient and modern. We’re animated, in part, by a primordial past. And that aggregate experience and evolution is available if you learn how to tap into it. That’s what the artist does. In the paintings, the audience can encounter these avatars outside the history books, in a contemporary context that carries the full weight of collective consciousness and makes it symbolically available for exploration.

Throughout history and cultures, men and women have dressed up to emulate the gods; to borrow the wisdom, or energy, or power their archetypes carry. I’m doing the same thing. To serve the search. To share. Like a message in a bottle or a time capsule. A kind of parapsychological lure that pulls you in, offers you what your spirit or psyche might be seeking: a mirror, or a looking glass, or a magical place to escape to. To find vestiges of the self and integrate them into your current reality or identity.

Follow Rob Mango here.

At any point of conception in developing a painting, I fix the current image in my mind and set out on a blistering run, during which it changes and evolves in complex detail due to the oxygen debt that carries up a rich, inspirational infusion from the subconscious. My mind’s eye functions like a computer screen where I move around paint passages, insert and delete objects, deconstruct, and reconstruct…until I return to the studio, where I go to work, bringing those ideas into painted form.” Rob Mango