In an age of ephemeral digital storage, artist Taylor Smith is turning the relics of tech history into textured, compelling works of art. Based in Indianapolis, Smith has gained attention for transforming old floppy diskettes into vivid paintings — each piece bridging memory, material, and meaning. We spoke to Smith about the stories buried in outdated tech, their artistic process, and what it means to give discarded data a new visual language. Culturalee spoke to Taylor Smith in her home town of Indianapolis about her artistic practice and inspirations.

What first drew you to floppy diskettes as an artistic medium? Was it a personal connection to the technology, or more about exploring the contrast between analog and digital?

The first time I stumbled across a box of old floppy disks in a closet (my own from years earlier) it felt less like rediscovery and more like a confrontation with time. These objects had once stored parts of my life: early personal writing, college projects, digital fragments of an analog world, all with my own distinctive handwriting from that era. But in that moment, they were obsolete, quietly decaying relics that I would likely never use again. Yet there was something intimate and eerie about that contrast, something that needed to be saved, even preserved. That feeling—the ghost of data, the texture of memory—immediately struck me as something I wanted to explore visually.

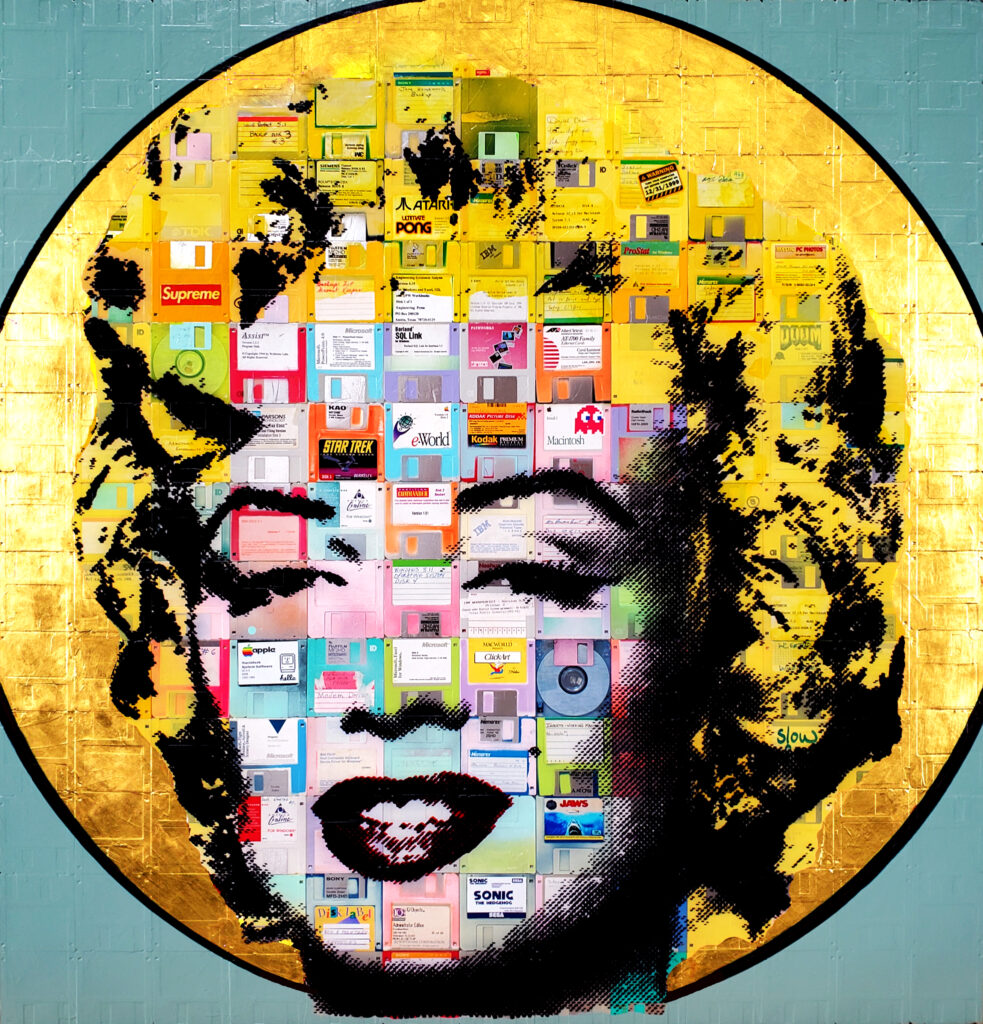

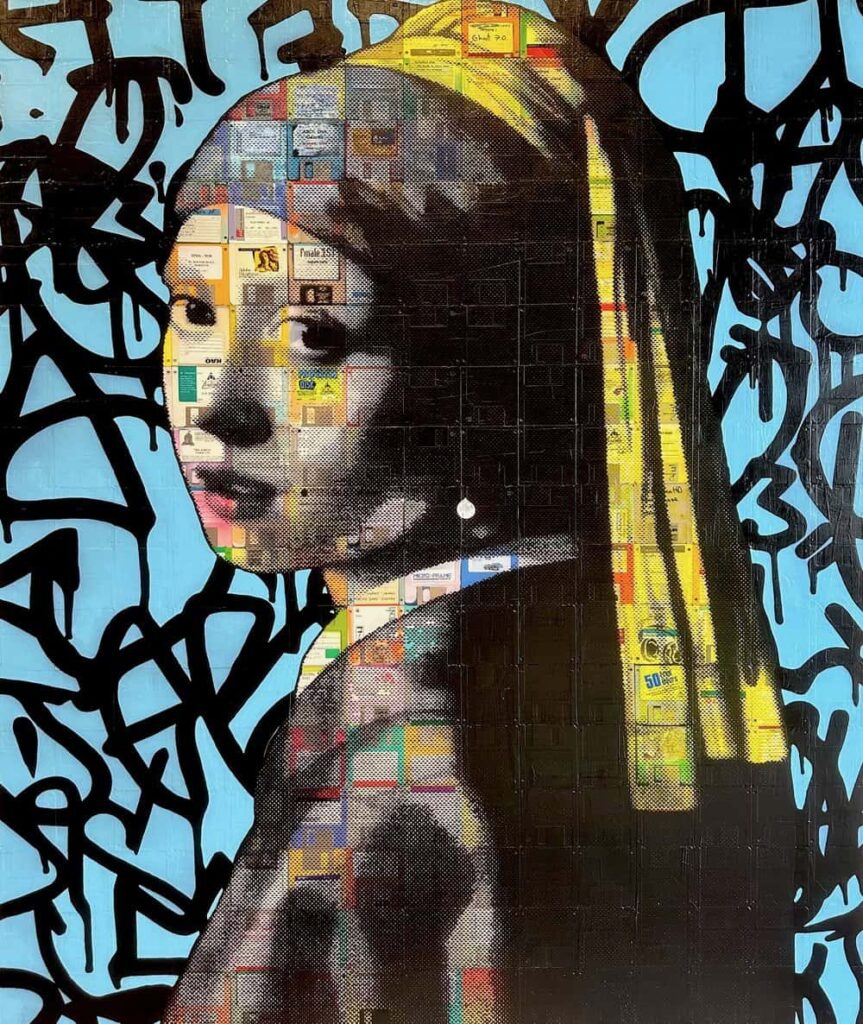

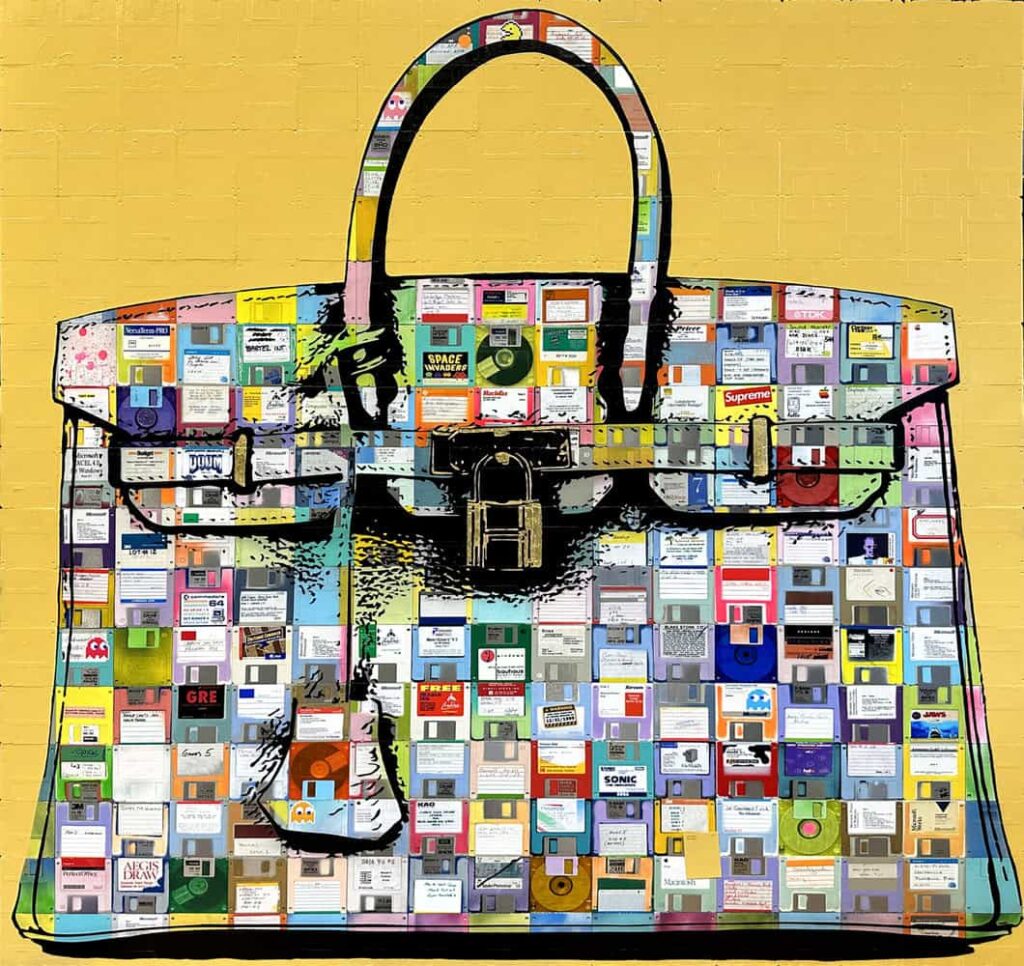

What I found most compelling was the paradox they represent. Floppy disks were, at one time, at the very frontier of digital progress, and now they sit at the bottom of junk drawers, unrecognized by modern machines. Using them as a physical foundation for paintings allows me to embed that contradiction directly into the work. It’s both a meditation on obsolescence and a kind of resurrection.

How do you decide which diskettes to use — is there any meaning tied to what they once stored?

Absolutely. What they once stored is part of the magic. When I come across old diskettes at online auction websites, at thrift shops or purchasing them from computer recycling companies, I’ll sort through them individually and hand paint each and every diskette. There are hundreds of thousands of them at this point in my studio and each one feels like a small masterpiece of its own with unique software labels and someone’s handwriting that will one day come together to make a larger composition. Sometimes the disk labels indicate what is stored inside like spreadsheets, DOS files, or outdated software. Other times, it’s fragments of someone’s life: a love letter, a short story draft, an address book. These ghost files become collaborators in the work, anonymous voices echoing from the past.

While I never open them or view the information stored on each disk, I use that exterior label reference to guide the spirit of the painting. If the disk was used for accounting software, it might become the base for a painting that critiques capitalism. If it held someone’s family holiday photos, I might use it for a portrait or a nostalgic Americana scene. The physical label on the disk—written in ballpoint or faded Sharpie—adds another layer of found poetry to the work.

You have artistic genes– your mother was an artist who went to Andy Warhol’s first show at the Ferus Gallery in 1962 in Los Angeles and passed up a chance to purchase an original Soup Can painting for $100. Did your Mother tell you stories about her days as a young artist in LA that inspired you on your creative path?

She did and those stories were like oral folklore in our family. My mother was a young woman who traveled the country and the world throughout the 1960s, during one of the most vibrant cultural moments in American art history. She wasn’t just around it, she was absorbing it, internalizing it. Her story about Warhol was one of both admiration and gentle regret, but, more importantly, it was a testament to how quickly art can shift from obscure to iconic.

She would talk about going to gallery openings, rubbing elbows with people who didn’t yet know they’d be legends. I think hearing those stories planted something in me early on: not just a fascination with pop art but a sense that great art doesn’t always start in museums. It starts in studio garages, small spaces, and overlooked media. That gave me the confidence to explore unconventional materials like floppy disks without second-guessing their artistic worth.

You studied art in Nurnberg and Berlin where you and some other students to helped prep the base layer for Keith Haring’s iconic mural on the Berlin Wall in 1986, and you hung out with Haring and members of the Checkpoint Charlie Museum afterwards. That must have been a seminal experience. How would you describe the experience and how it influenced you?

It was unforgettable. Being part of something so historically and visually potent at such a young age burned itself into my creative DNA. Haring was incredibly generous and kinetic and watching him paint was like witnessing jazz in motion. We were prepping the wall—mixing base colors, securing surfaces—but the real gift was just being near that moment, that energy.

What it taught me was that art doesn’t have to be confined to canvas or gallery space. It can confront power, assert itself in public spaces and become a living part of political history. The Berlin Wall wasn’t just a barrier, it became a global sketchbook, and Haring’s work there turned it into a loud, joyful protest. That experience deeply informed how I think about the power of visual language and its ability to document time, place and resistance.

What did you think of art school in Germany and how did the art world of Germany in the 1980s shape the artist you are today?

German art education in the 1980s was rigorous, philosophical and emotionally intense. It wasn’t about producing gallery-ready work, it was instead about deconstructing everything you thought you knew. We were steeped in theory, criticism and discourse. There was no hand-holding, but that kind of environment taught me to interrogate every artistic choice I make.

At the same time, being in Germany in the 80s—especially Berlin—meant you were constantly surrounded by political tension and artistic rebellion. The art world there wasn’t slick or polished, it was raw, performative and fiercely intellectual. I would also take advantage of my American passport and travel through the checkpoints to visit East Berlin, which at the time was still communist and quite controlled. I would attend gallery openings and go out to dinner with East German artists. It was such a creative experience, but at the same time it felt slightly dangerous and to a young person like myself that was simply heavenly. Artists like Sigmar Polke and Anselm Kiefer were challenging everything—history, memory, nationalism—and their work gave me a vocabulary for thinking about materials not just aesthetically but ideologically. That left a permanent mark on how I approach my practice.

There’s a strong tactile quality to your work. What role does physicality and texture play in your creative process?

I’ve always felt that the eye alone can’t tell the whole story of a painting—you have to feel it, even if only visually. The physicality of working with wood panels, vintage tech and layered epoxies and art materials is integral to how I process ideas. There’s something ritualistic about assembling the disks, sanding, painting and sealing. It’s sculptural in many ways, even though it hangs on a wall.

Texture invites the viewer to slow down. In an age of digital oversaturation, where everything is a quick scroll, I want people to linger, lean in, squint, notice a file label on a disk or a ripple under the paint. It’s in those moments of pause that memory, material, and meaning start to connect.

What’s the actual process like from disk to painting? Do you treat the diskettes like a canvas, collage element, or something else entirely?

The diskettes function as both surface and subject. I start with a composition in mind—usually a pop icon, a vintage and known object, or sometimes a phrase. Then I select and arrange the disks like tiles based on colors I have individually painted them, label, and texture. Once they’re mounted onto a wood panel, I begin working over them with different materials, paint and sometimes resin. It’s a balance of preserving their individuality while unifying them into a cohesive image.

Sometimes I’ll leave certain disks completely exposed, especially if they have handwriting or unusual branding. Other times, I’ll paint over them heavily and sand them back down to let parts peek through. It’s not just about what’s visible, it’s about what feels embedded. The disks aren’t a gimmick, they’re collaborators.

Your work feels nostalgic, but also quite forward-thinking. Do you see yourself commenting on digital decay or data permanence?

Very much so. There’s something poetic about the idea that we once trusted these flimsy plastic squares to hold entire archives of our lives—resumes, letters, taxes, games—and now they’re unreadable to most people. That fragility fascinates me. It says something about our belief in permanence in an age that changes faster than we can archive it.

In using these materials, I’m asking viewers to consider what we keep and what we discard digitally, emotionally, culturally. Will today’s cloud storage have the same nostalgic power thirty years from now? I can’t imagine how, but it may very possibly evoke those feelings. What will we miss when it’s gone? My work is an attempt to capture that fleeting relationship with technology and memory.

Many artists are exploring “found” materials, but you’ve gone deep into obsolete tech. How do you think that sets your work apart?

Obsolete tech carries a specific weight of memory that other found materials don’t always hold. A floppy disk isn’t just a thing, it’s a container of forgotten information. It had a function, a user, a purpose. There’s a built-in intimacy to it. I think what sets my work apart is the effort to preserve that narrative, to treat it with reverence and curiosity rather than irony.

Also, the repetition of using hundreds of disks in one piece adds a meditative, almost architectural quality. It’s not just about upcycling or nostalgia, it’s about creating a visual language out of the remains of our digital past. A grid upon which to create an artwork. That kind of specificity resonates with people who lived through the tech shift, but also intrigues younger viewers who’ve never used a floppy disk in their lives.

Indianapolis isn’t always the first place people think of for experimental art — how has the city shaped your practice?

That could be true and maybe that’s why it works. Being based in Indianapolis has given me the room and freedom to develop a voice without chasing trends or needing constant validation. Indianapolis has a very vibrant and interesting art scene. I think it beats the art scenes found in many much larger cities, frankly. My studio is in a converted loading dock of a 1901 brick building with 30-foot ceilings and skylights that was formerly an industrial dairy. It’s massive, industrial and perfect for working on the scale I do. It gives me space to breathe and think.

The Midwest also offers a unique perspective. There’s a rich tension between nostalgia and progress here. I think that duality shows up in my work. And while the art scene might be quieter than in cities such as Chicago or Miami, there’s a strong, supportive creative community that values authenticity over hype. That’s allowed me to grow organically.

Your work seems to live at the intersection of memory, material, and media. Is there a particular emotion or question you hope to evoke in viewers?

I hope people feel a sense of recognition, a flicker of memory, even if they can’t quite place it. I’m not trying to dictate a single message. Instead, I want the work to function like a visual time capsule, sparking different associations for each viewer. It might remind someone of their first computer. For someone else, it might evoke feelings of loss or transformation.

Ultimately, I think the question that lingers is: what do we leave behind? What objects, images, or data points represent who we were? And what happens when those artifacts lose their original function? My goal is to create beauty and tension in those unanswered questions.

Which artists, past or present, do you feel a kinship with in terms of material use or conceptual themes?

I’ve always felt connected to artists like Richard Pettibone, Warhol and Sigmar Polke for their play with cultural imagery and process. Ed Ruscha’s dry wit and text-driven pieces were foundational for my word-based painting series. And of course, I admire Wayne Thiebaud for the way he found joy in repetition, surface, and Americana.

I also feel a kinship with artists who elevate overlooked materials—El Anatsui with his bottle caps, or Joseph Cornell with his assemblage boxes. There’s a quiet poetry in giving discarded things a second life. That’s what I strive to do with my floppy disks: preserve their ghosts, highlight their beauty, and let them speak again in a new language.

All images © Taylor Smith.