Post Human VII brings together nine contemporary artists who translate their creative visions into exquisitely handwoven carpets, blending fine art and craftsmanship in a striking new collaboration between CMJZ Arts, curator Tobias Ross-Southall, and Thames Carpets. Presented at the new Cramer St Gallery in Marylebone Square, the exhibition features works by Hayden Kays, Helen Beard, Sola Olulode, Saman & Sasan Oskouei, Tom Furse, James Massiah, Mays Al Moosawi, Michael McGrath, and Tobias Ross-Southall himself.

Reimagining the historical significance of rugs and tapestries through a contemporary lens, Post Human VII celebrates the timeless artistry of weaving as a form of modern expression — creating handmade, collectible works that bridge culture, time, and technique. As Ross-Southall notes, “In a divided world, this project affirms the power of art to unite.”

Post Human VII runs from 14th October to 9th November at the new Cramer St Gallery, Marylebone Square.

Tom Furse

This project brings contemporary artistic visions into dialogue with the ancient craft of weaving. How do you see the act of translating digital or conceptual ideas into handwoven carpets reshaping our understanding of both mediums?

I see big parallels in a woven image and a digital image – they both can be thought of as a dense mass of individual points forming a larger whole, so in many ways being able to draw a line between traditional weaving and digital artwork makes a lot of sense. And where there are distinctions that’s a very curious place to explore. On a screen the light comes from behind the image – on a rug the light falls on the image, dispersed by tiny strands of wool. It’s a completely different creature that way, and yet the fundamentals are extremely similar. For an artist like me whose work mostly takes place within the digital sphere, any opportunity to bring that work into the physical world can be both challenging and exciting. On a screen, the image is backlit and coloured with absolute precision, every pixel there to be tuned. As soon as the work becomes physical the characteristics and limitations of that medium enter the conversation. It requires you to relinquish an element of control – there’s always a level of anticipation to see how the work translates. Being an artist whose practice has been focused around generative processes for many years now, this actually feels entirely normal to me. I like not knowing. It’s like collaboration with a silent partner – you’re never quite sure how they’re going to interpret your idea, and how their interpretation will inspire your next step.

Historically, rugs and tapestries have been carriers of cultural memory and symbols of power. What kinds of narratives or cultural shifts do you hope this collaboration with Thames Carpets will capture for our time?

For me the opportunity to work with Iranian weavers is fundamentally an honour. In its own tiny way it chips away at the geopolitical messaging forced on us every day. I believe we should be working together, sharing our resources, sharing our expertise – creating together, imagining better futures. However there are those who could impose politically motivated restrictions on these rugs – an illegal rug – absurd really, no? In this reality the very existence of these rugs becomes a small act of defiance – a small of group of people working across continents to create timeless beauty that exists in a state of resistance.

The works are described as both sculptural and political–objects and surfaces. Can you speak to how the materiality of weaving offers a unique platform for contemporary artists to explore these dual roles?

I learned recently that the code used for the 1969 moon landing was woven using copper wire. The Apollo Guidance Computer relied on “core rope memory” – core rope memory was fixed: once woven, it could not be changed. It was read-only memory built from magnetic cores through which wires were threaded. Each wire that passed through a core represented a binary “1”; each wire that bypassed it represented an O.” Essentially the program’s code, made from thousands of instructions, was physically threaded into hardware. If you wanted to change the code you had to reweave it. In this we can see weaving as a kind of permanence, a binding together to create something resilient and meaningful in the slop era.

In a world often marked by division, this project emphasizes unity and shared vision. How do you imagine audiences and communities engaging with these woven artworks–as collectors, viewers, or participants in a larger cultural dialogue?

It’s difficult to predict such things. Some will see an interior design object, to be placed on the floor. Others will see an artwork, to be hung on the wall. Those in the middle will be left with a tortuous conundrum. One thing I always think of is how a child would see it – how I think of the objects and artworks that really captured my imagination as a child, and how they stayed with me, influencing me to this day. If I can make that impression on a young mind that may well be the most meaningful engagement I can think of.

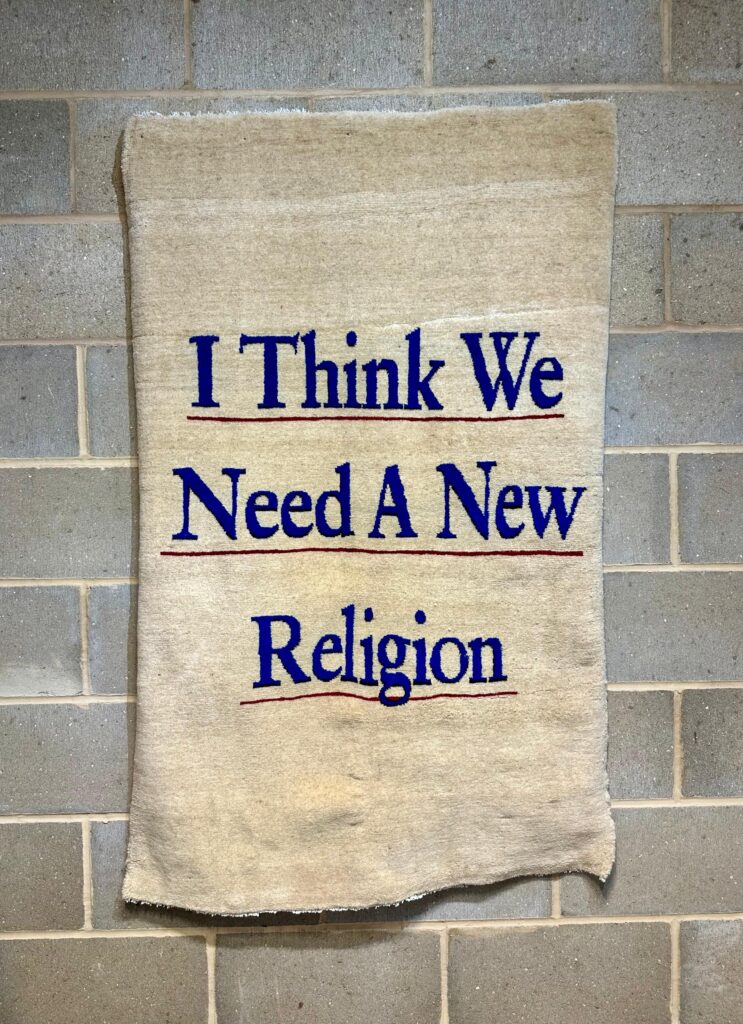

James Massiah

In a world often marked by division, this project emphasizes unity and shared vision. How do you imagine audiences and communities engaging with these woven artworks–as collectors, viewers, or participants in a larger cultural dialogue?

I can’t say how people will respond. I know what I’m commenting on and what I’m referencing. I always just try to make work that I’m proud of and that speaks to something that I’m passionate about. In this case it’s a call to reconsider how we structure our lives and also who we offer our devotion to.

James Massiah

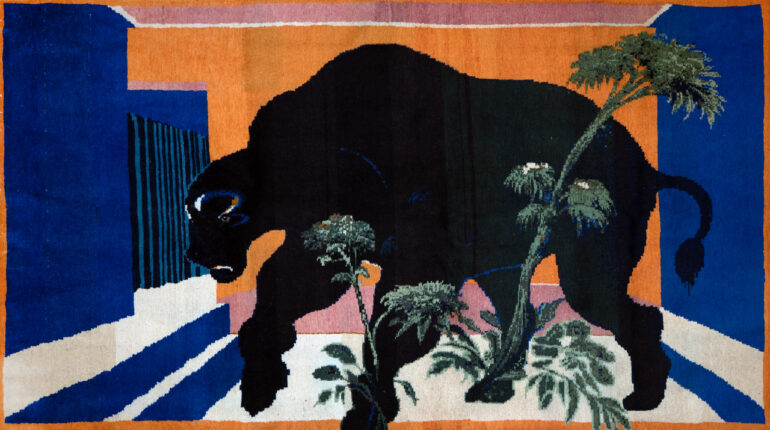

Michael McGrath

This project brings contemporary artistic visions into dialogue with the ancient craft of weaving. How do you see the act of translating digital or conceptual ideas into handwoven carpets reshaping our understanding of both mediums?

I typically work quickly and instinctively, letting mistakes and chance shape the image. Seeing those marks carefully reinterpreted and woven by hand adds another layer of meaning, where something impulsive becomes intentional and enduring.

Historically, rugs and tapestries have been carriers of cultural memory and symbols of power. What kinds of narratives or cultural shifts do you hope this collaboration with Thames Carpets will capture for our time?

My current work explores how real and imagined histories overlap through mythology and memory. This collaboration continues that idea, reflecting a desire for tangible history and visual expression that captures the contradictions of our time, both fragile and durable, ancient and futuristic.

The works are described as both sculptural and political–objects and surfaces. Can you speak to how the materiality of weaving offers a unique platform for contemporary artists to explore these dual roles?

I’m always teaching myself new mediums and have been experimenting with tufting and weaving, but I don’t have the patience required to create these works the way I envision them. I’m drawn to the space between the urgency of creation and the patience that the medium demands. A carpet’s surface is something you walk on and live with, intimate and everyday, yet it also holds meaning and depth. These layers often go unnoticed, but they are present each day, just underfoot.

In a world often marked by division, this project emphasizes unity and shared vision. How do you imagine audiences and communities engaging with these woven artworks–as collectors, viewers, or participants in a larger cultural dialogue?

I see them as invitations to conversation and to new ways of thinking. They hold traces of experience that can be touched and lived with.