The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure, curated by writer and former Institute of Contemporary Arts director Ekow Eshun, showcases the work of contemporary artists who are illuminating and celebrating the richness and complexity of Black life through their artistic practice.

The National Portrait Gallery exhibition runs from 22nd February to 19th May, and features 55 contemporary works of sculpture, painting and drawing by 22 African diasporic artists working in the UK and America. Alongside a magnificent new bronze sculpture by Thomas J Price titled ‘As Sounds Turn to Noise’ and created especially for the National Portrait Gallery, the exhibition includes many works displayed in the UK for the first time, as well as paintings rarely shown in public art galleries. The Time is Always Now explores the depiction of the Black form within portraiture and features contemporary works made between the year 2000 and today.

The Time is Always Now seeks to question what it means to visualise the Black body. The exhibition’s title is taken from an essay on desegregation by the American author and civil rights activist James Baldwin who said: “There is never a time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.”

Eshun’s sensitive curation is a deliberate shift from the objective to the subjective; from looking at the Black figure to seeing through the eyes of Black artists, and the result is a long overdue study of the Black figure and its representation in contemporary art. The traditional Portraiture documented by art history and exhibited in museums for years was notorious for white-washing, and guilty of overlooking the black figure. So it’s about time museums and galleries give more of a platform and voice to black stories, narratives and artists. As well as surveying the presence of the Black figure in Western art history, the exhibition examines its absence. Eshun uses black figuration and portraiture to explore the story of representation, whilst examining the social, psychological and cultural contexts in which the artworks were produced.

The exhibiting artists include; Michael Armitage, Lubaina Himid, Kerry James Marshall, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Amy Sherald, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Hurvin Anderson, Michael Armitage, Jordan Casteel, Noah Davis, Godfried Donkor, Kimathi Donkor, Denzil Forrester, Lubaina Himid, Claudette Johnson, Titus Kaphar, Kerry James Marshall, Wangechi Mutu, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Chris Ofili, Jennifer Packer, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Thomas J Price, Amy Sherald, Lorna Simpson, Henry Taylor and Barbara Walker.

Curator Ekow Eshun gave an incredibly insightful and moving speech at the press view, which gave some important insights into the curation: “This exhibition ‘The Time is Always Now’, is based on this period of extraordinary of visibility in terms of Black artists, and also this long history of the Black figure being overlooked, the ‘underseen’ within art history. It begins also from the consciousness that we talk about ‘Blackness’. This too is an idea. This too is a proposition. Race itself is a scientific fiction, it has no basis in fact. There is no biological or genetic difference between people with different skin colours, other than skin colour. Nevertheless, race itself remains one of the single ways by which we understand and navigate the space between us. So race has a lived reality. So in this context, in the context of these different histories of being overlooked, being misrepresented, being underseen, what does the depiction of the Black figure by a Black artist in this contemporary moment, what does this look like, and what are the implications of that. This is some of the territory that the show explores. Double Consciousness, Persistance of history and Kinship and Connection.

These are many different perspectives and positions that ultimately occupy a shared ground of discovery, of assertion, of presence, of celebration, contemplation, reflection. Twenty-Two artists, and if there’s one thing that unites those artists, that joins together those artists. If there’s one thing, I would suggest it’s this: that if we consider this long art history of the Black figure being looked at, being gazed at, if we think about long social histories of Black people being ‘othered’, being rendered alien in the Western imagination, these artists invite the shifting gaze. They invite the shifting gaze of looking AT the Black figure, to looking WITH or through the eyes of the artist or subject that they depict. This is the pivital shift for me, this is the hinge on which the show stands: the shifting gaze of looking AT the black figure to looking with, thinking from. This is what happens when Black artists depict the Black figure. They speak from a subjective position.”

It’s serendipitous that ‘The Time is Always Now’ should open at the NPG only a few weeks after the critically-acclaimed ‘Entangled Pasts’ exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, as both exhibitions make a concerted effort to correct the imbalance of cultural representation in art, which was historically biased towards white artists and their representations of white figures. Both exhibitions capture the zeitgeist of a long overdue celebration of African and African diaspora artists who have made a huge impact on contemporary art over the past few decades, and artworks by Barbara Walker and Lubaina Himid can be found in the NPG and RA exhibitions. Also, several of the paintings featured in ‘The Times is Always Now’ have been previously exhibited at the Venice Biennale (Michael Armitage and Noah Davis), or been the subject of major museum shows (Lubaina Himid at Tate Modern) and important survey exhibitions celebrating art from the African diaspora (Chris Ofili in Tate Britain’s recent Life Between Islands’ exhibition). Consequently, ‘The Time is Always Now’ presents a unique opportunity to see work by some of the most exciting and celebrated black artists working today, thoughtfully curated and presented in one venue.

Curator Ekow Eshun was motivated to remind people through this exhibition that, while Black artists are experiencing a moment of flourishing, their work exists within an always-evolving artistic lineage. Eshun explores three core themes in this exhibition; Double Consciousness, Persistence of History and Kinship and Connection.

Double Consciousness was first introduced as a theory in 1903 by African American sociologist, W.E.B Du Bois and works displayed in this section of the exhibition explore concepts of being, belonging and Blackness as a psychological state, whilst reacting to stereotypes and the memorialization of Black lives. Double Consciousnessexamines the ways in which artists see themselves, as well as how they are seen and framed by others, navigating real and imagined identities.

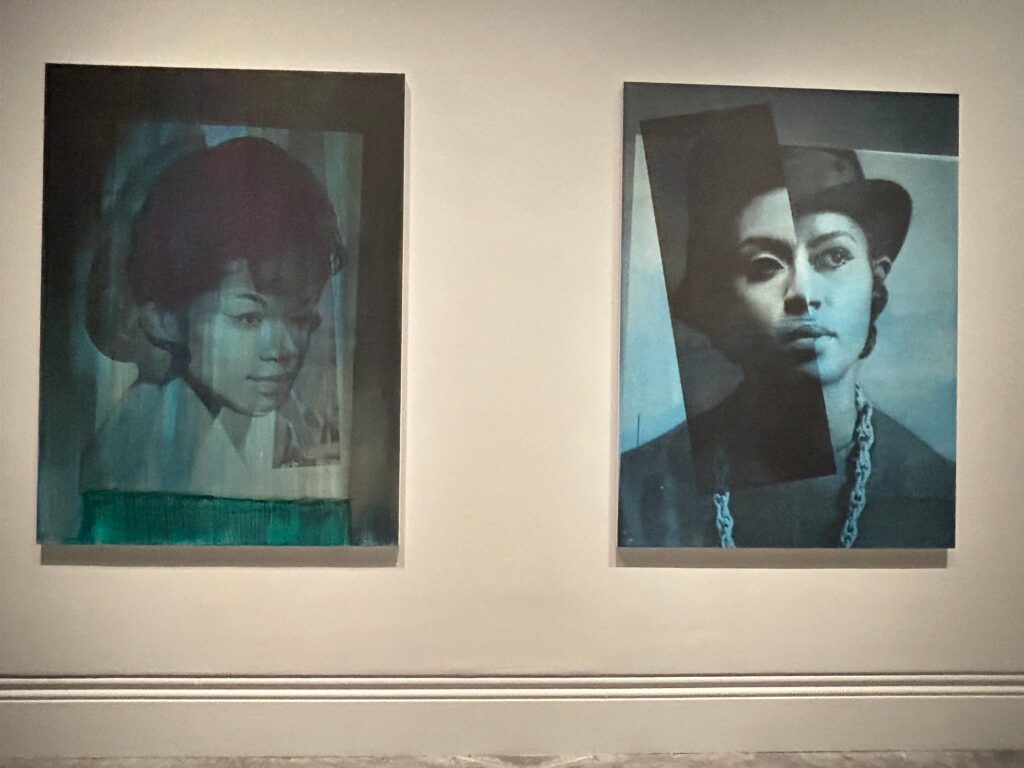

At the entrance to the exhibition Lorna Simpson’s two blue-tinted screenprints ‘Blue Tulip’ (2023) and ‘Rope Chain’ (2023) reveal through repetition the reinforcement of stereotypes in the everyday imagery we consume. Thomas J Price’s majestic bronze figure ‘As Sounds Turn to Noise’ was created with 3D scans of people from London and Los Angeles, amalgamated to create a hybrid portrait, which highlights the fluidity of identities beyond social and racial profiling.

A series of evocative portraits by Amy Sherald are given their own room, and feature life-size, greyscale portraits of African American subjects with a direct gaze, and succeed in shifting the focus away from the sitters’ skin colour onto their interiority, enabling them to claim the visibility that has long been denied to Black people in art. Several fragmented portraits with almost cubist facial features, by American figurative artist Nathaniel Mary Quinn, explore how self-perceptions, and those made by others, are physically expressed.The Time is Always Now invites a shift in perspective, encouraging viewers to ‘see through’ the eyes of Black artists and the figures they depict, rather than simply ‘look at’ them.

Another room features a powerful series of paintings by Noah Davis, Michael Armitage and Jennifer Packer, and a bronze sculpture of a sleeping head by Kenyan-born American artist, Wangechi Mutu, which bears a striking resemblance to Constantin Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse (1910), which evoked the influence of African masks, Native American totems and Oceanic tiki figures.

Frequently depicting the everyday lives of Black Americans, in scenes that often blend the real and surreal, Noah Davis’ Black Wall Street (2008) also builds on notions of history and memorialisation. The title refers to Greenwood, Oklahoma – known as ‘the Black Wall Street’ – prior to the moment in 1921 when it became the site of a two-day-long massacre by a white mob, one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history.

Kenyan-British artist Michael Armitage’s vast canvases have a sense of magical realism, and are painted on traditional Lubugo bark cloth, with allusions to Western art history permeating the paintings. Kenyan middleweight boxer, Conjestina Achieng is depicted in Conjestina (2017) in a Gauguinesque landscape. Four paintings by Kerry James Marshall complete the Double Consciousness section, and confront the invisibility ascribed to Black bodies in the Western pictorial tradition by reinserting Black figures and moving them from the periphery to the centre.

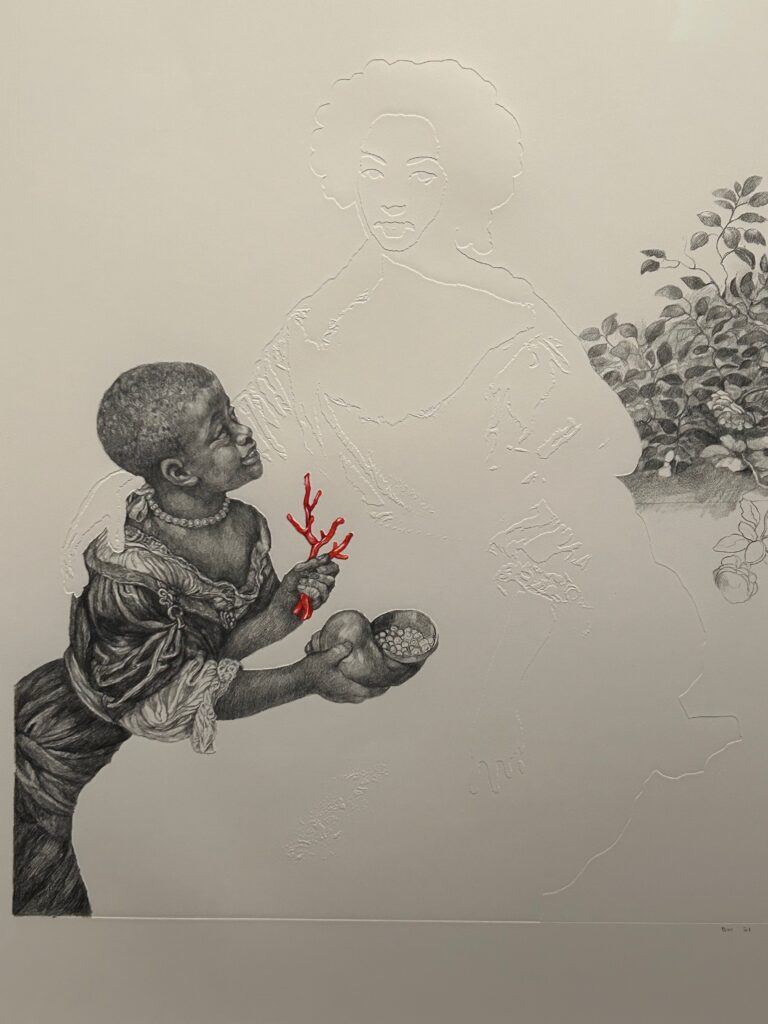

Persistence of History is the second curatorial theme of the exhibition, and presents artists who are examining the exploration of presence, and absence, of black characters in historical narratives, commencing with a display of five drawings by British artist Barbara Walker. In Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard) (2021), Walker recreates a historic portrait of Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth with an unknown female attendant (1682) by Pierre Mignard, which is part of the National Portrait Gallery’s own Collection. Walker’s drawing reduces the named Duchess of Portsmouth to an embossed outline and, instead, shines a light on the ‘unknown female attendant,’ rendering the young servant girl in exquisite detail.

American artist Titus Kaphar confronts history by deconstructing how it is conveyed through the visual language of Western painting. Like Walker, Kaphar draws attention to what has been removed or forgotten, reconfiguring Western art history to include the African American subject. In Seeing Through Time 2 (2018), the artist combines two paintings – one to conceal and one to reveal – again, removing the presence of Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth, and replacing her silhouette with a contemporary Black female figure.

Building on this, Kimathi Donkor also uses the tradition of history painting to restage important events from history and tell the often forgotten or overlooked narratives of people who fought for freedom. Paintings by British-Ghanaian artist Godfried Donkor explore the triumphs of Black protagonists: St Thomas, up to scratch (2019) and St Bill Richmond, the black terror (2019) depict African American heavyweight boxers Tom Molineux and Bill Richmond, both of whom were born into slavery and fought their way to freedom.

Further hidden histories are uncovered in the work of Lubaina Himid. Le Rodeur: The Exchange (2016), a painting that responds to a case of blindness that struck the French slave ship, Le Rôdeur, in 1819. Without their sight, the captives were deemed worthless and were thrown overboard to drown. Refusing direct representation in her work, Himid instead encourages viewers to imagine the victims’ fear and disorientation by removing any sense of cohesion.

Kinship and Connection is the third and final theme of The Time is Always Now, and features works that respond to assertions of Black assembly and gathering. While many of the exhibited artworks depict scenes of joyful gathering, references are also made to histories of segregation and oppositions to public expressions of Black sociality. This dual theme of hostility and welcome is explored by British-Jamaican artist, Hurvin Anderson, whose paintings which unpack the cultural significance of the barbershop to the Caribbean diasporic community are shown alongside Itchin & Scratchin (2019) by Denzil Forrester, and Chris Ofili, whose dancing figures reference the mythical douens of Trinidadian folklore.

Toyin Ojih Odutola’s drawings depicting wealthy Black figures in fictional homes, consider the social construct of class in relation to race, sexuality and gender, and while Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens (2021) by Njideka Akunyili Crosby portrays the Nigerian-born, Los Angeles-based artist in her garden. Jordan Casteel’s figurative paintings capture intimate moments with people she encounters on the streets of Harlem or on the New York Subway, while Henry Taylor’s drive to capture life extends to the communities closest to him, revealing the social and political forces that come to bear on American life.

“The Time is Always Now celebrates a period of extraordinary flourishing in the work of artists from the African diaspora. My hope is that the exhibition encourages audiences to look more closely at the imaginative reach of the exhibiting artists; the ways they are illuminating the richness and complexity of Black life through figuration, and simultaneously asking searching questions about race, identity and history. All while creating artworks that are never less than dazzling.”

Ekow Eshun, Curator, The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure

“The Time is Always Nowis a celebration, bringing together 22 of the most important and exciting artists working today. Collectively, their work explores the richness and potency of Black being, its unrestricted possibility and the beauty of Black presence – from culturally significant paintings by Kerry James Marshall and Chris Ofili to new work by Thomas J Price and Toyin Ojih Odutola, never-before-seen in the UK. As alluded to in the exhibition’s title, there is no better time than now to stage this exhibition – so my sincere thanks to Ekow Eshun for his commitment and vision in realising such a consequential exhibition. We also thank Bank of America for their support.” Dr Nicholas Cullinan, Director, National Portrait Gallery

Following its display at the National Portrait Gallery, The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure will travel to The Box in Plymouth (29 June – 29 September 2024) before touring to the USA.

The exhibition catalogue, The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure by Ekow Eshun, includes contributions and essays from Man Booker Prize winning author, Bernardine Evaristo; Scotiabank Giller Prize winning novelist, Esi Edugyan; and art historian, Professor Dorothy Price. The exhibition will also be accompanied by the publication Reframing the Black Figure: An Introduction to Contemporary Black Figuration by Ekow Eshun.

The Time is Always Now is supported by Bank of America, which has enabled a reduced £5 ticket seven days a week for all visitors aged 25 and under, with the aim of broadening access to the arts for young people.

The Time is Always Now is at the National Portrait Gallery until 19th May, 2024: https://www.npg.org.uk/whatson/exhibitions/2024/the-time-is-always-now