Azam has painted portraits of iconic figures from contemporary culture including Queen Elizabeth II and Malala Yousafazi, created public sculpture for the University of Aberdeen and London City Airport, had a major solo exhibition at London’s prestigious Saatchi Gallery, and exhibited around the world. His art can be found in museum collections including the Ben Uri Museum and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts.

These are just some highlights of an extraordinary career that has seen him go to extreme lengths for the sake of art, including a trek to Antarctica where he painted in ice caves and in an ice desert, and a pilgrimage to Lake Saiful in Kashmir with musician and composer Soumik Datta. Azam was born in Jhelum, Pakistan, and moved to the UK with his family in the 1980s. He lives and work between Birmingham and London. Azam’s artistic practice involves an ongoing exploration of his experience of diaspora and exile, including recent projects such as the Diaspora Project and Dog Days, a reflection on the racism directed at the first Asian Prime Minister of the UK.

Culturalee interviews Azam about his career so far, his mission to democratize art through public installations such as the Diaspora Project, as well as upcoming projects in California and Pakistan.

You have worked on some incredible projects during your career, and have gone to some extreme lengths for the sake of your art. For example, your expedition to Antarctica and to the mountains of Pakistan, for the project Saiful Malook. What has been the highlight of your career to date?

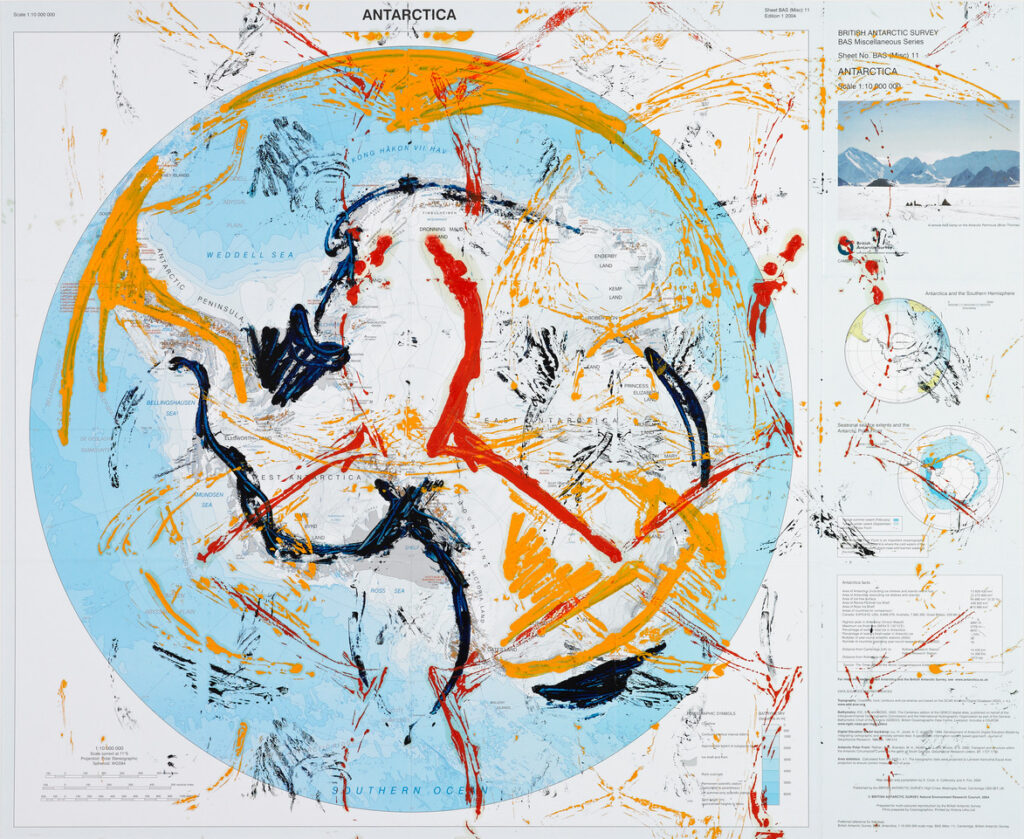

Yes, I’ve been fortunate to have worked on a number of pretty major projects, which have been logistically and practically challenging. For me, it was a matter of going to extreme environments, and seeing how that effected my vision, and the work that I made. It is a bit like Monet, you know, having to be outside in the landscape where he painted, rather than hiding in the studio, but taking this to an extreme. Antarctica was a really harsh environment, and presented major difficulties, but thanks to a really good team we managed to paint in ice caves, and in an ice desert. Some of the paintings are still there, buried in Antarctic ice.

In 2019 you had a major solo exhibition at Saatchi Gallery, which was inspired by your pilgrimage to Lake Saiful in Kashmir. Was it a spiritual quest or a mission to delve deeper into your heritage, and how did you interpret the journey visually in your art?

It was a bit of both – I had come across the poem ‘Saiful Malook’ by the Sufi saint Mian Muhammad Bakhsh in the early 1990’s through a musical project Peter Gabriel was doing, and he had included a Qawwali singer from Pakistan named Ustad Nusrat Ali Khan, who had translated the poem into his musical interpretation. I just fell in love with the song and then found that the Sufi saint came from the same city, Jhelum I was born in, around 150 years before. So, with that strong connection, I wanted to visit the lake as a creative project but wanted to collaborate with a musician – and it was amazing I could do the visit with the very talented musician and composer Soumik Datta.

The terrain & logistics were probably as tough as the Antarctica project – but the journey was a lot deeper given the context and heritage and especially given my own pre-conceived ideas of the poem. The creativity was centred around painting in situ on different locations and of the lake – including a work that I did in the lake on a floating canvas and trying to incorporate the main themes of the poem. We managed to visit the lake on full moon, which is a key element of the poem, and where I completed my painting ‘Full Moon for the Princess’.

Soumik created music at each point of the collaborative creative process, and I was pleased with the Saatchi show which incorporated film, photography and paintings done in situ and after the visit and encapsulated the pilgrimage well. It was amazing to show that Antarctica paintings and the Saiful Malook works together.

You have painted portraits of some powerful, iconic women including the Late Queen Elizabeth II and Malala Yousafazi. How do you choose your subjects and what is your method for painting portraits?

I wanted to make images of powerful women, and it was incredible to receive the commission to make an official portrait of Malala. Her portrait was done from studies and photographs that I took when I met her, but the painting captures her personality, showing her dressed in her familiar and instantly recognisable red dress. The portrait of Margaret Thatcher, titled (Blue Lady, 2012), was in fact based on a painting by Picasso — although I’m not sure what Thatcher thought of Picasso! I painted Queen Elizabeth using her younger image but dressed in Elizabethan costumes to signify her longevity and the impact she had as the longest serving monarch.

Malala Yousafazi’s family commissioned your portrait of her, which is on permanent display at the University of Birmingham. What was Malala’s reaction to her portrait, and did it feel like a full circle moment for you to have the painting exhibited at your Alma Mater?

I was honoured to share our Pakistani origin and to unveil her portrait at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, where I had my first show back in 1983 and which is part of Birmingham University where I studied. Her portrait was done from studies and images I did when meeting her and the large size of the painting captures the huge impact she’s had on girls’ education around the world. She had seen the studies I had done but only saw the finished piece at the unveiling. I mentioned the aim of the size in my speech, and she appreciated it during her remarks, where she also mentioned she was proud to be a Brummie! And it was very fitting that the painting is now part of the University’s collection and permanently displayed at the Institute of Translation Medicine, which is a collaboration between the University and QE II Hospital, where she was first treated.

You’re a multi-disciplinary artist and have created some epic public sculpture during your career including Athena at London City Airport (the tallest bronze sculpture in the UK) and a sculpture at the University of Aberdeen. How does your approach to creating sculpture differ to the method you use for portraits or immersive art experiences?

It was really exciting to work on monumental public sculpture projects and to create in bronze on such large scale. It’s fascinating that the process hasn’t changed in thousands of years and modern technology can’t interfere with it. I feel content that these works will be in-situ for a long time, but it is a type of work that I am not currently engaged with. As an example, Athena at London’s City Airport took me five minutes to create but five years to fabricate and in essence turned out to be more of an engineering project.

But the whole experience was enlightening – as shortly after getting the necessary approvals, we realised that there wasn’t a foundry in the UK which had done bronze sculpture at that scale – so I ended up buying Morris Singer Foundries, who were responsible for most of the public sculpture in the UK over the last century like the Lions of Trafalgar Square, to fabricate in time & it was amazing to work with the craftsmen and craftswomen.

Another inspiring project was working in collaboration with the renowned Danish architects, schmidt hammer lassen who were working on the futuristic library in Aberdeen University. We decided to go with my bronze sculpture, Evolutionary Loop 517 at the entrance, marrying the new technologies with the old. The name was selected by the university in a competition they held and signifies the age of the university.

Your most recent public art installation ‘The Diaspora Project’ involved displaying paintings in public spaces around London. How did you choose the locations and how did the project come about?

The Diaspora Project is a continuation of my fascination of democratizing art, which initially came about with my public sculpture. During lockdown I did a portrait of the Queen with a NHS mask in oil and hung it outside my studio in Islington. I was intrigued as to how resilient the painting was – and after two years I still have it up and it looks surprisingly fresh. A more recent inspiration for the project was the acquisition by the Ben Uri Museum and Gallery of two early paintings, from the 1980s, made after I arrived in Britain with my family from Pakistan. I began to realise who important the experience of diaspora, of exile, was for millions of people around the world, and how being part of that community can be a positive thing. So, I thought how I can show case my original paintings as a permanent public space installation and selected all the areas in London I have lived in since arriving from Pakistan as a child in 1970. The project proved to be a real logistical challenge given the approvals and installation requirements, but now that the paintings are up, I am planning a detailed narrative for the project and add works relevant to the Diaspora experience. As an example, I painted Dog Days on the cusp of the recent elections to capture a dramatic moment in British politics — racism directed at the first Asian Prime Minister of the UK — that sheds light on the tensions still at work in our society, and which shaped my own upbringing. The Diaspora Project is an ongoing, permanent, evolving and a very personal initiative for me.

What projects do you have coming up that you’re allowed to talk about?

Alongside ongoing work on the Diaspora Project, I am working on a series of works for public display in Beverley Hills, California and planning a project later this year in Pakistan, exploring the rich heritage via local traditions and crafts and collaborating with artisans there. We are also working on ideas for a project creating works about British waterways and the coastal environment, creating a connection with the paintings I made in the mountains of Kashmir and Antarctica.

For more information on Azam go to: https://www.azam.com