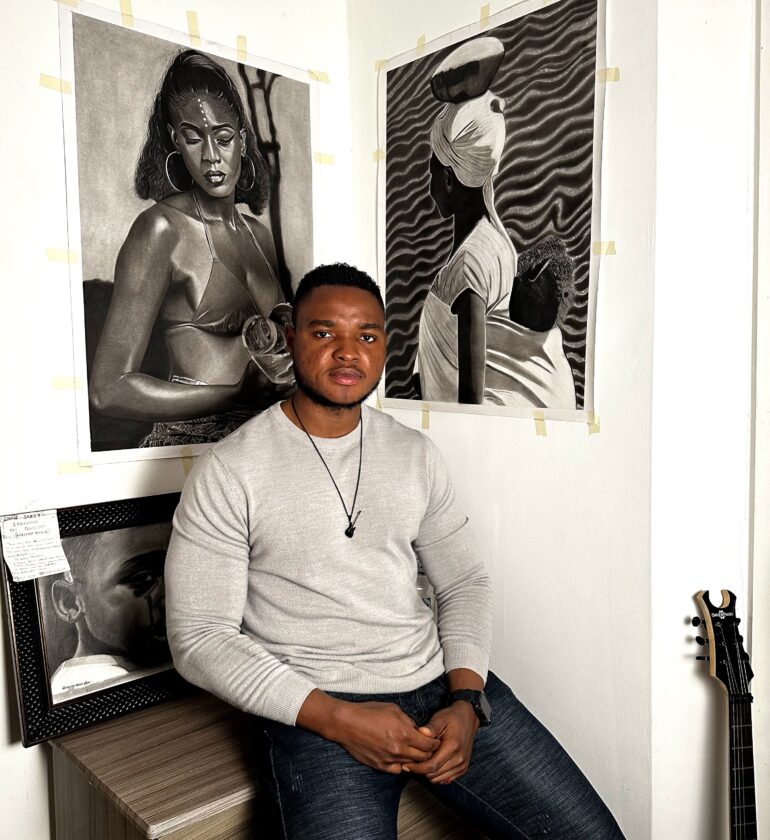

Emerging Artist Series

In this edition of Culturalee in Conversation‘s new series of interviews with emerging artists, we sit down with Emmanuel Ayinuola–better known in the art world as Emmie Jazzy–a hyperrealist artist whose pencil work blurs the line between reality and imagination. With an eye for detail that borders on the obsessive, Emmie Jazzy creates stunning portraits that not only showcase technical mastery but speak volumes about culture, identity, and representation.

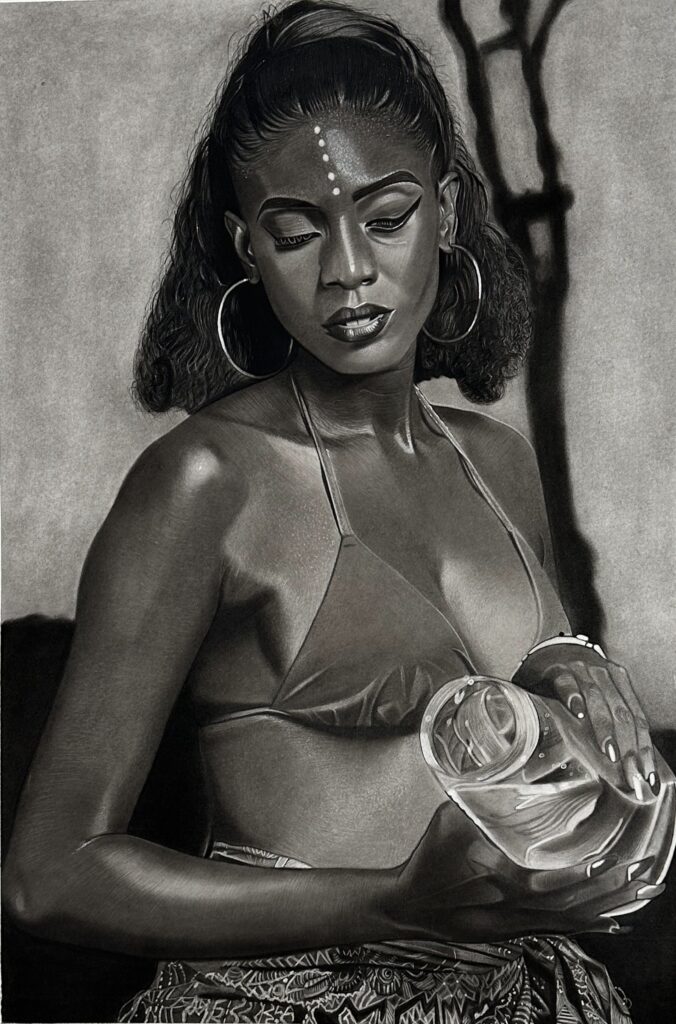

Rooted deeply in his Nigerian heritage, Emmanuel’s art is both a tribute and a statement–a powerful reminder of the richness of African identity and the importance of Black visibility in creative spaces. Through each stroke, he channels a profound mission: to inspire, uplift, and give voice to Black children, using his craft as a mirror through which they can see themselves in all their beauty and potential.

Join us as we explore the passion behind his hyperrealism, the cultural threads that run through his work, and the purpose that fuels every portrait he draws.

What first drew you to the genre of hyperrealism, and what does it allow you to express that other styles might not?

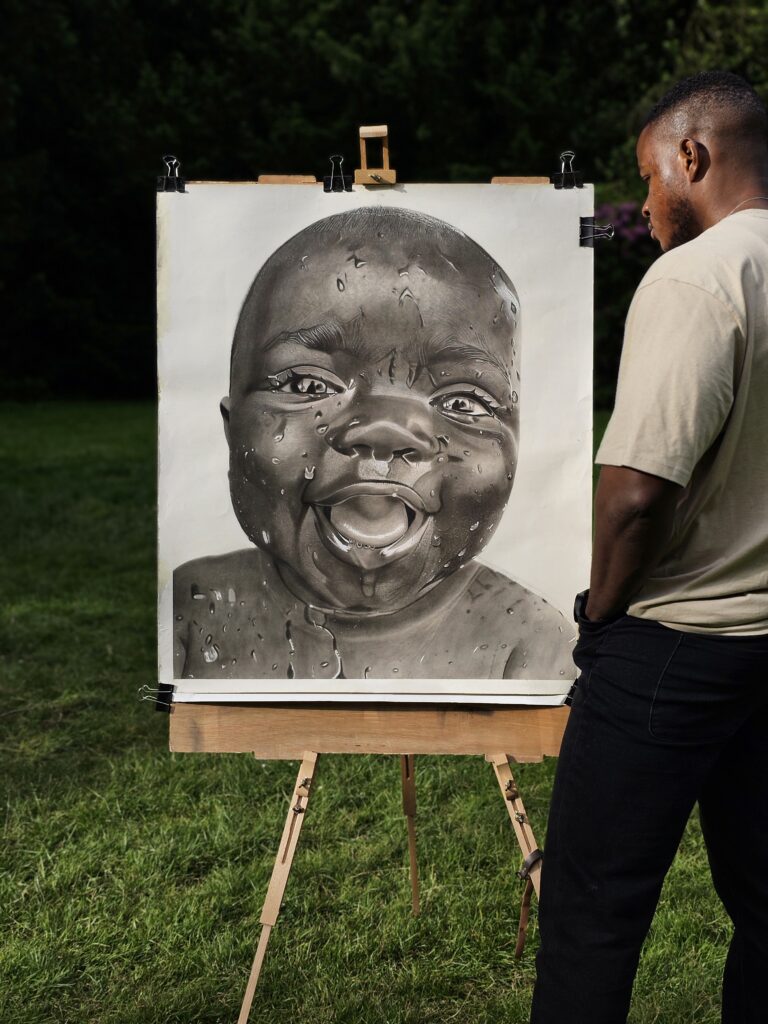

From my earliest days in primary school in Nigeria, I was captivated by the precision of drawing — the challenge of capturing not just a likeness, but a soul. Hyperrealism became my language because it allows me to communicate at an intimate, almost confrontational level with the viewer. Every pore, wrinkle, and subtle change in tone becomes a narrative in itself. While other styles can suggest emotion, hyperrealism allows me to embody it — to create works that hold your gaze and invite a deep conversation about the subject’s lived experience.

Are you influenced by renowned hyperrealist artists such as Duane Hanson, Ron Mueck, or Chuck Close–and if so, in what ways has their work shaped your own?

I admire each of them for different reasons–Hanson’s social commentary, Mueck’s ability to manipulate scale to provoke awe, and Close’s devotion to process despite personal challenges. But my influences are equally drawn from African portraiture traditions, where representation is layered with cultural and symbolic meaning. These artists taught me that realism can be more than replication; it can be a platform for storytelling, activism, and connection.

Your work often carries messages of love and equity–how do you use your art to communicate these themes to your audience?

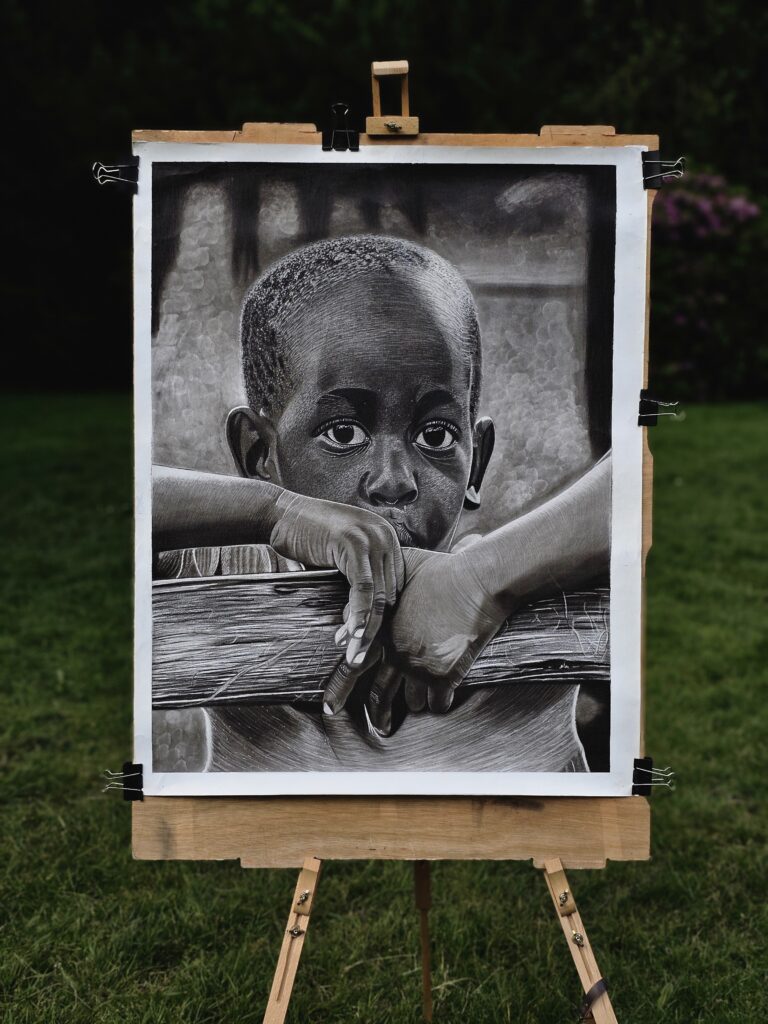

Love and equity are woven into the stories I tell through my subjects. Whether it’s the quiet dignity in a child’s eyes or the subtle celebration of African beauty and heritage, I aim to create images that honour humanity in all its forms. The detail in my work forces the viewer to slow down–to truly see the person, not just glance at the image. In that pause, there’s room for empathy, and empathy is the foundation of both love and equity.

You’ve described your work as being a voice and a source of empowerment for Black children–can you talk about how you see yourself as a role model through your art?

Representation is powerful. Growing up, I rarely saw art that reflected my community with dignity and depth. I want Black children to see themselves not just included but celebrated in the highest forms of fine art. If my work can inspire a child to believe their story is worth telling—that their face, their struggle, their heritage, and their dreams deserve a place in galleries and collections—then I’ve succeeded. I hope to be a visual reminder that their potential is limitless.

How does your Nigerian heritage influence your work, and are there any Nigerian artists who have particularly inspired your practice?

My Nigerian heritage is my foundation–from the vibrancy of our fabrics to the rhythm of our music and the resilience of our people. It has taught me to tell stories with both strength and tenderness. Artists like Ben Enwonwu have inspired me with their ability to merge African narratives with global art language. I also admire the detailed, realistic works of artists like Kelvin Okafor, Arinze Stanley, and contemporary Nigerian artists who, like me, straddle multiple worlds while staying rooted in their origins.

Can you walk us through your creative process — do you work primarily in pencil, do you use photographs as references, and how long does it typically take you to complete a piece?

My process begins long before the first mark — it starts with the story. Once I have the narrative, I gather references, often photographs, sometimes a live sitting, and compose the image digitally before committing to paper or canvas. I work primarily with charcoal, sometimes blending with acrylic or pastel to create texture and depth. My hyperrealistic works are incredibly time-intensive — smaller pieces can take 75–100 hours, while large, detail-rich works can take 200–250 hours. That investment of time is part of the meaning: it reflects the care, respect, and presence each subject deserves.

Find out more about Emmie Jazzy at: https://emmiejazzy.com