Van Gogh and the Roulins. Together Again at Last at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is one of the most intimate Van Gogh exhibition in years, an extraordinary reunion of portraits that have long lived apart. Following its debut at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, this Amsterdam iteration brings together a substantial grouping of the 26 paintings Vincent van Gogh made of the Roulin family during his incandescent, turbulent months in Arles. The result is an exhibition that not only reassembles a dispersed visual family but illuminates the profound emotional bonds that sustained one of art history’s most fragile geniuses at a defining moment.

© VAN GOGH MUSEUM, AMSTERDAM (VINCENT VAN GOGH FOUNDATION)

The story begins in the summer of 1888, when Van Gogh arrived in the blazing light of Arles, hopeful that Provence would rejuvenate both his creativity and his dreams of establishing an artists’ community. Instead, he found himself battling loneliness, financial precarity, and the spiralling pressures of mental illness. Amid this uncertainty, a steadfast friendship took shape with a man who came to embody stability: Joseph Roulin, the bearded, broad-shouldered postmaster of the Arles train station.

The Roulins–Joseph, his wife Augustine, and their children Armand, Camille, and baby Marcelle–welcomed Van Gogh as a friend. Their warmth and ordinariness offered an emotional anchor in a life increasingly marked by instability. This deeply human connection forms the core of the exhibition, which brings their portraits together as if gathering the family once again in Van Gogh’s Yellow House.

The exhibition opens in an unexpectedly moving way. Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Straw Hat stands beside a simple willow-frame chair, an object so modest it could easily be overlooked, yet here it resonates like a relic. Long stored in the museum’s collection and too fragile to travel to Boston, it is shown publicly for the first time: the very chair on which the Roulins sat for Van Gogh, and the same chair immortalised in his iconic paintings.

At some point we thought we should put the Chair in the exhibition. Of course it makes sense. But it couldn’t travel to Boston because it’s so fragile. Really, it’s the perfect moment. It has been waiting for this.” Curator Nienke Bakker

Placed at the threshold of the exhibition, the chair’s presence is almost spectral. One thinks instantly of Van Gogh’s painting of his bedroom in Arles, where another unadorned chair sits beside the neatly made bed, a symbol of domestic simplicity charged with the absence of its owner. Here in Amsterdam, the original Arles studio chair acts as a quiet stand-in for Van Gogh himself, a material trace of his studio, his solitude, and the conversations that once unfolded within its orbit.

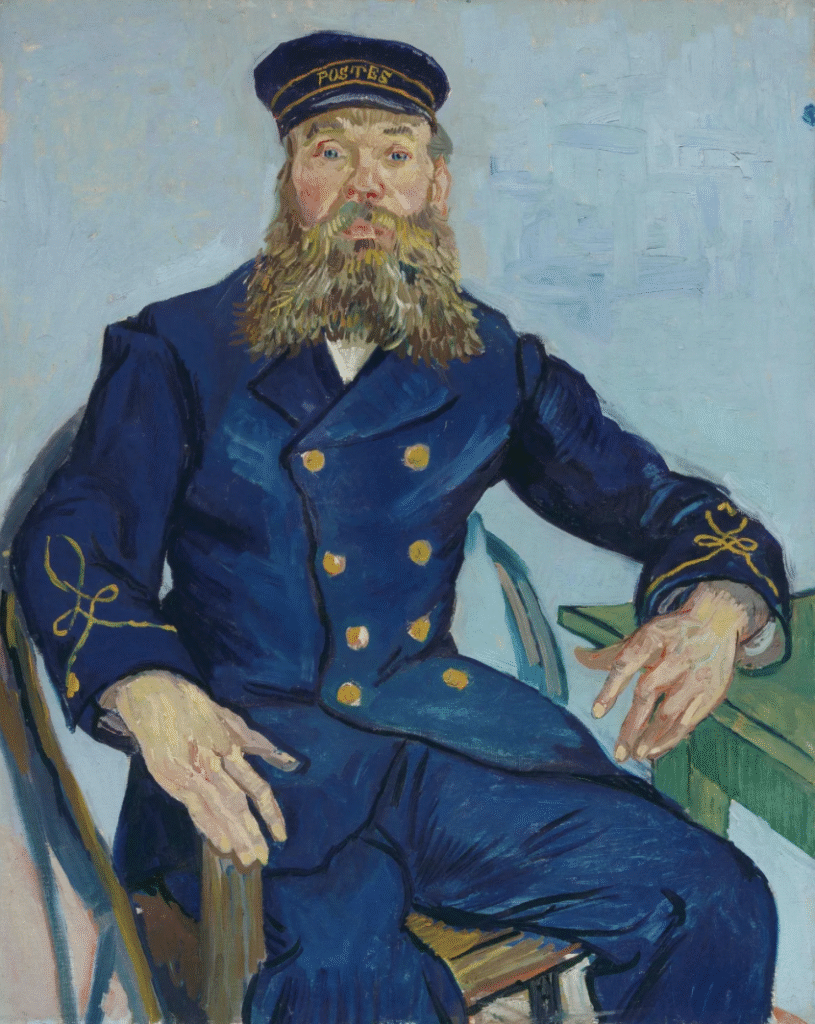

The chair becomes the gateway into the exhibition’s first portrait: Joseph Roulin seated in his rich navy postman’s uniform, rendered with swirling strokes and a beard that seems almost sculpted in paint. It is one of Van Gogh’s most psychologically alive portraits and, paired with the physical chair, it creates a triangulation between sitter, artist, and object that gives the room a startling intimacy.

Van Gogh painted Joseph multiple times, drawn to his steadiness and to the luminous contrast of blue and gold in his official attire. In letters to his brother Theo, he compared the postman’s wisdom and gentleness to that of Socrates. Standing before these portraits, the comparison feels surprisingly apt.

Bakker clarifies how the two men met: “They probably met in the café, where Van Gogh was living above before he moved to the Yellow House. They would also have run into each other at the station, where Joseph was working. Van Gogh would go there to send paintings to his brother in Paris and also to pick up shipments of canvas and paint.”

Their friendship, rooted in such everyday encounters, grew into something familial. In contrast to the volatility of Van Gogh’s relationship with Paul Gauguin–who appears early in the exhibition in a small portrait that silently confronts the studio chair–Joseph Roulin offered constancy. A painting of Gauguin’s Chair (1888), shown later in the exhibition, pulses with tension: its deep reds and greens feel electric, as though vibrating with the psychological strain of the artists’ failed collaboration.

Where Gauguin fled after Van Gogh’s breakdown, the Roulins remained. Joseph wrote letters of encouragement; Augustine visited him in hospital. Their loyalty permeates the portraits, imbuing them with a warmth that transcends their often feverish colors.

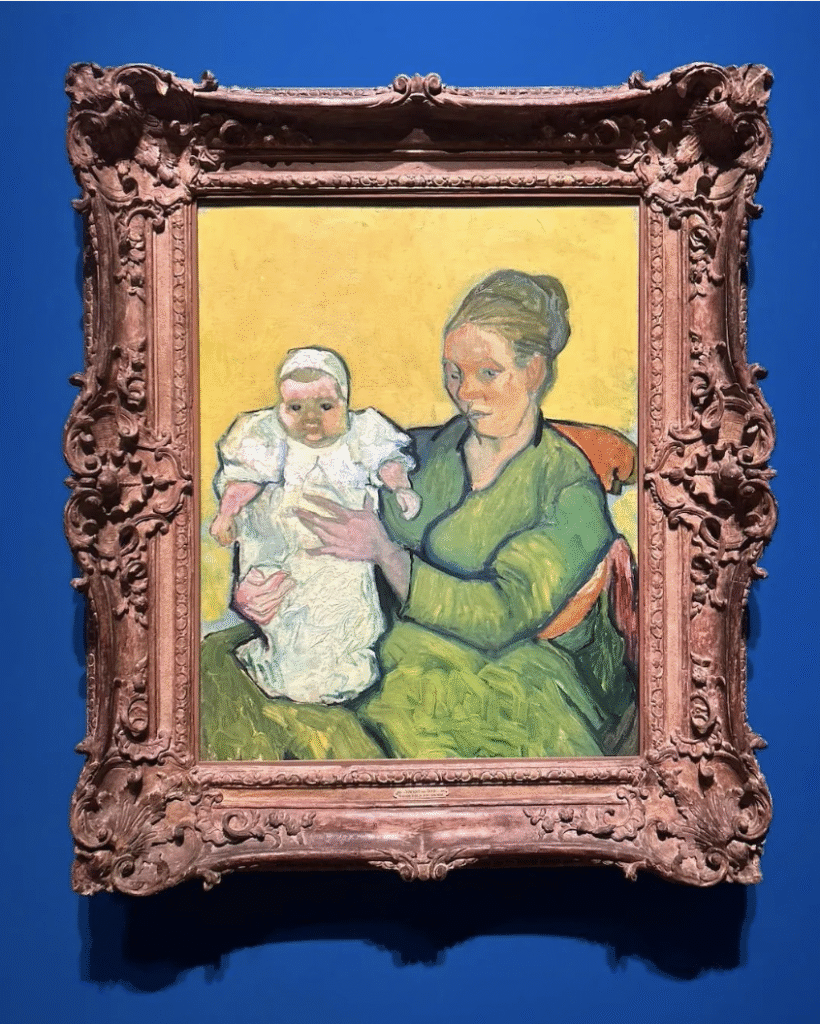

One of the exhibition’s most captivating sequences is the group of portraits of Augustine Roulin as La Berceuse (The Lullaby). Augustine appears seated, holding a rope meant to rock a cradle just beyond the picture’s edge, a gesture that becomes both literal and metaphorical. Van Gogh imagined these paintings hung in a sailor’s cabin so seafarers might be soothed, “reminded of their own lullabies.”

In these works, Van Gogh is at his most experimental. Inspired by Japanese woodblock prints and floral motifs from his mother’s garden, he set Augustine against a series of bold, decorative backdrops. Across the variations, the flowers shift from representational blooms to almost abstract fields of color, reflecting the oscillation of his psychological state during and after his hospitalization.

The emotional tension is subtle but palpable: Augustine’s serene presence appears to steady the swirling visual world around her, as if embodying the maternal reassurance Van Gogh so often craved.

Bakker and co-curator Katie Hanson weave the Roulins into a broader art-historical context. Sightlines link Van Gogh’s portraits to Rembrandt’s humanity, Frans Hals’s quicksilver brushwork, and Daumier’s compassion for working people. These comparisons are not academic adornments; they demonstrate how deeply Van Gogh absorbed, studied, and reinterpreted the masters. His genius here is not solitary but dialogic—an artist in conversation with history, refining portraiture into an expressive, psychological art form.

The reunion of fourteen Roulin family portraits in one space feels revelatory. Armand appears solemn and introspective; Camille glows with youthful mischief; Marcelle, barely more than a baby, radiates innocence. Taken together, the works read like chapters from an intimate novel—a family saga painted not by an outsider but by someone who loved them.

For viewers accustomed to the blazing yellows of Sunflowers or the celestial swirl of Starry Night, these portraits offer something quieter but equally profound. They reveal Van Gogh’s belief that ordinary people–postmen, mothers and children–could embody universal archetypes. Painting them again and again, he refined not only his technique but his understanding of human connection.

Ultimately, Van Gogh and the Roulins is more than a reunion of canvases. It is a portrait of a friendship that shaped an artist’s life at a moment of profound vulnerability. By inviting viewers into Van Gogh’s inner circle, the Van Gogh Museum has crafted an exhibition that reveals the artist’s humanity through the people who accepted him without hesitation. Their images endure not merely as works of art but as testaments to loyalty, compassion, and the quiet heroism of ordinary lives.

Van Gogh and the Roulins. Together Again at Last is on view at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until 11 January 2026.