In his powerful, multidisciplinary practice, artist Arilès De Tizi explores the emotional and political terrain of migration, memory, and decolonized identity. Born in Hussein Dey, Algiers, and raised in the working-class suburbs of Paris after fleeing the Algerian civil war, de Tizi creates work shaped by diaspora, displacement, and resilience. Moving fluidly between painting, photography, and installation, he fuses devotional iconography with urban visual languages, recasting migrant and anonymous figures as monumental, sacred presences.

In this Culturalee in Conversation, de Tizi reflects on growing up between Algeria and France, the influence of thinkers like Frantz Fanon and James Baldwin, and the lasting impact of raï, jazz, and medieval hymns on his visual language. Speaking from his lived experience across Paris, New York, and Tokyo, he shares how art becomes a site of reconstruction – where inherited histories, exile, and memory are transformed into acts of visibility, dignity, and quiet resistance.

Your work often explores what it means to be a decolonized person to reconstruct identity in the aftermath of displacement and inherited histories. How has your Algerian heritage, and the experience of growing up in France as part of the diaspora, shaped your understanding of self and the figures you depict in your art?

I was born in a story that had already begun long before me. Algeria gave me a sense of origin. That density of silence and light you carry almost without knowing it. France gave me something else, a language shaped by exile and suspicion. A way of existing slightly off the side, slightly against the grain.

Growing up in the diaspora means learning early that identity is never a solid block. It’s more like a tremor. You inherit wounds that are not entirely yours, yet they carve the way you see the world. The figures I depict are from that place, where intimate memory meets colonial archives.

I am not trying to recount History. I am trying to show what History leaves behind. Bodies crossed by forces larger than themselves, bodies that somehow manage to remain standing.

You’ve spoken through your work about living in the space “between exile and belonging.” How do you translate that tension of being both inside and outside multiple cultures into your visual language across painting, photography, and installation?

Living between exile and belonging means learning that the center is a mirage. I am always slightly out of alignment, as if no land fully accepts my weight. But that displacement is not a lack, it is a fertile space. In my artistic language, whatever form it takes, I try above all to keep that tension alive without seeking to resolve it. Painting allows me to inhabit absence. Photography gives me speed, intuition. Installation gives the unrest a body, a breath. I never look for harmony, only for a fragile kind of coherence, the physical sensation of being both foreign and intimate at the same time. What I make is not a translation of exile, it is its texture.

Your practice draws on a wide spectrum of references from Frantz Fanon and James Baldwin to medieval hymns, raï, and jazz. How do these intellectual and musical influences inform the emotional and political rhythms of your work?

These influences are companions, not scholarly references. Long before Fanon and Baldwin, to name only them, there was already in me the intuition that identity is shaped in its fractures and fault lines. Fanon illuminated the fact that identity can be an inner war. Baldwin showed me that vulnerability can become a form of incendiary clarity. Raï is the Algeria of the streets, a nostalgia that never apologizes for itself. Jazz is breath, improvisation as an act of survival. In medieval hymns, as in Berber chants, I find the taste for the sacred, the sensation of being crossed by something that exceeds us. All of this blends in my work like layers of voices. They are rhythms, surges, fractures. They give the work a political pulse, but a politics that begins with emotion, with the way a face trembles or a red tone sinks into the black.

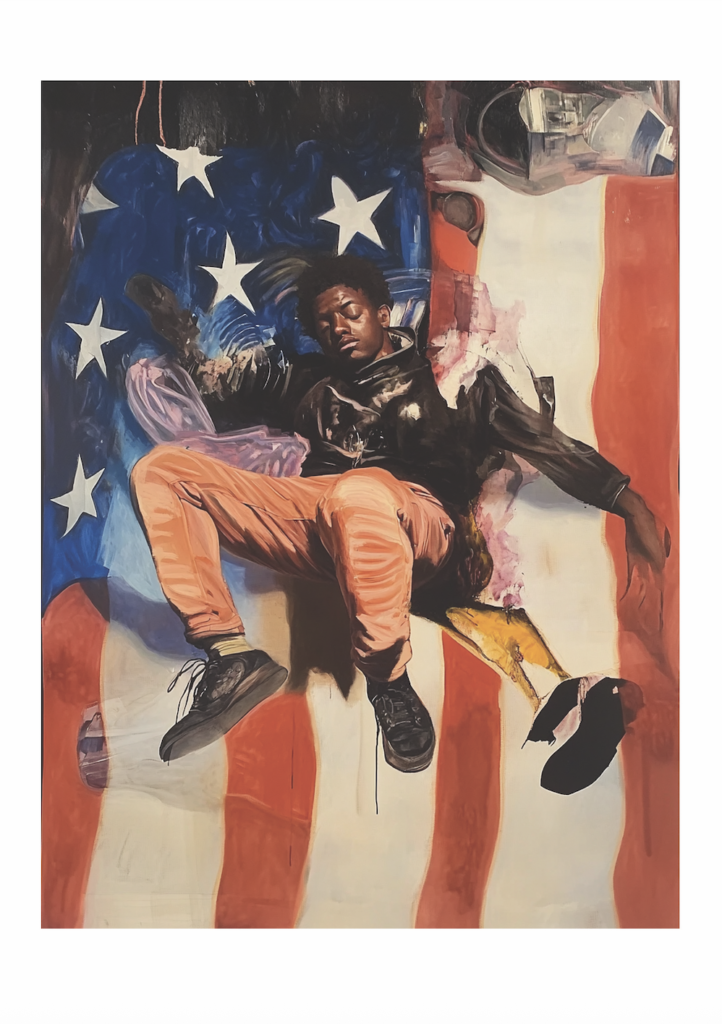

Your paintings often reimagine migrant or anonymous figures as monumental and sacred, transforming them into symbols of resilience. What drives this act of elevation, and how does it challenge or subvert traditional Western portrayals of the “other”?

I have never wanted to depict migrants as silhouettes in flight. I want to restore the verticality that the Western gaze has denied them. In my paintings, these figures become monumental not to be turned into heroes, but to reclaim their real weight, their presence. They are sacred because the sacred lies in recognizing the dignity of what history has tried to erase.

It is a way of overturning the frame. The “other” is no longer observed from a distance, he looks back at you. He occupies the center, he sets the rhythm. It is a silent form of resistance, a way of saying that no one is born secondary.

Your journey has taken you from graffiti in Paris’s subways to international exhibitions and collaborations. What visual or cultural references continue to anchor your work today, and how have your years living between Paris, New York, and Tokyo expanded the way you approach themes of identity and memory?

Graffiti was my first school. And it was more a school of survival than a school of art. When I look back, I realize that writing your name on a wall was a way of claiming your existence when no one else acknowledged it. With distance, I think that energy never really left me.

Paris gave me urgency. New York gave me amplitude, the possibility of reinventing myself without asking for permission. Tokyo taught me silence, precision, humility before the material. These cities are not backdrops, they are states of mind. They expanded my way of approaching identity as something in motion, something that circulates between languages, gestures, and faces.

Memory, for me, is not a place you return to. It is a territory you rebuild every time you create.

Growing up in the diaspora means learning early that identity is never a solid block. It’s more like a tremor. You inherit wounds that are not entirely yours, yet they carve the way you see the world. The figures I depict are from that place, where intimate memory meets colonial archives.”

Arilès de Tizi

Follow Arilès de Tizi here.