In this edition of Culturalee in Conversation, we speak with contemporary painter Trish Wylie, whose work crackles with fierce energy, cinematic references and an unapologetic engagement with gender politics. From her early paintings inspired by iconic Western movies – work that caught the attention of former Royal College of Art Rector Sir Christopher Frayling – to her current Menopausal Cowboy series, Wylie has consistently used film iconography, horses and expansive landscapes as vehicles for freedom, resistance and self-definition.

Rooted in childhood memories of growing up in South London, shaped by formative studies at Camberwell College of Arts, and fuelled by a lifelong fascination with Westerns, Wylie’s paintings explore what it means to inhabit female power across time. In this conversation she reflects on her artistic influences, studio practice, landmark exhibitions and her evolving relationship with painting as a physical, instinctive and deeply liberating act.

Looking back on your career, your early paintings inspired by iconic Western Movies won you a fan in the form of ex Royal College of Art Rector Sir Christopher Frayling. Can you talk about your love of Westerns and horses and how this fascination has influenced your artistic journey and this body of work in particular.

My love of Westerns started in my childhood in the 1950’s and 60’s where they were the equivalent to present day ‘Reality TV’ as a given staple on television. I was a ‘tomboy’ and very much identified with the men in these films as they led active exciting lives and often rode over vast landscapes with a wild and expansive terrain very different to what I was familiar with in

South London. I grew up in a 4 bedroomed council flat in London with 9 siblings, so indoor space was taken up with a lot of other people, but there were still bomb sites in London which made wonderful playgrounds for us kids to go and play on, they were a great substitute to play out our Cowboy games, imagining a Prairie or Desert in Stockwell.

Growing up in a large Irish Catholic family as a girl meant there was a huge expectation of you to embrace domesticity and to be there as a support to your mother, the boys did not have those expectations placed on them, and I resented being forced to accept expectations that I found dull and restricting.Westerns were a means of escape and expressing the male aspect to my psyche, I was very different to my mother. Westerns represented freedom to me both as a child and again as a middle aged woman, I chose to acknowledge that and embarked on my series of paintings from the film Magnificent Seven around 20 years ago.

Horses of course are the very animal that affords the cowboy the freedom to roam, with their power, speed and beauty, they are incredibly exciting. At that time you still would see horses in London pulling milk floats, coal carts, rag and bone carts and being ridden by police, often coming down our street.

The Irish love horses and my father was a harness and saddle maker, and there would be various horse stories from Ireland often recounted in our London Council Flat.

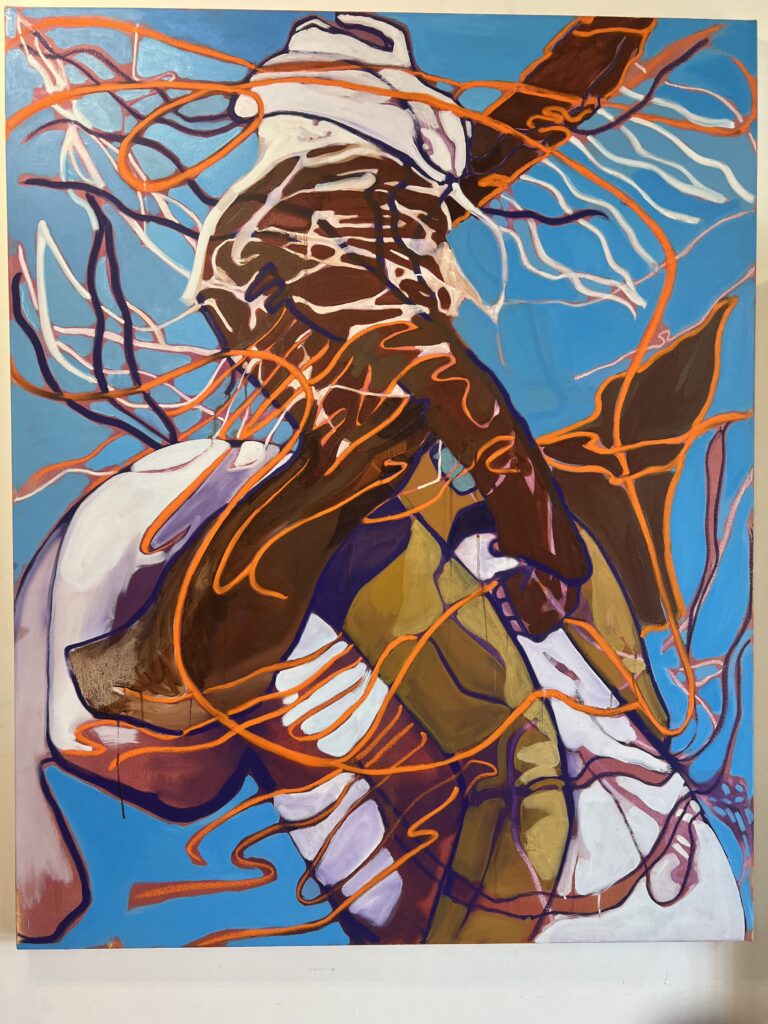

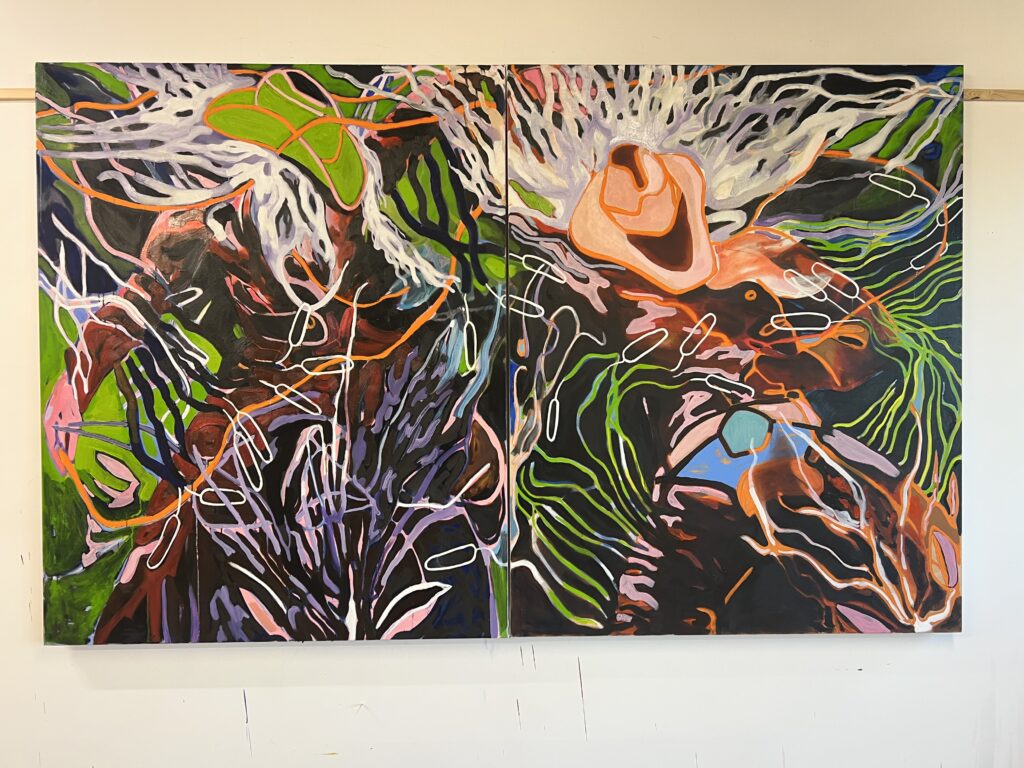

This recent body of work is almost like a return to my prepubescent self and is about a struggle for freedom and presence, expressing the continuous journey of being a female in our society. Now I’m post menopausal, it’s like lassoing my childhood energy. The world doesn’t see me that way, but that’s how I feel when I’m painting and that’s how I want to feel. I think maybe a lot of older women feel like it. When I am painting I have to push the paintings to embody those impulses in me and that is why I do not make any direct prep work for them, it all has to happen right there on the canvas just like in a Rodeo.

Who are your artistic inspirations and how did your formative studies at Camberwell shape your work?

I have many artistic inspirations and they are not all painters, its more about an attitude or an approach generally about making something creative and new happen, however when it comes to painters there are many, but my most recent artistic inspirations have been from Chris Ofilli and his “Seven Deadly Sins’ paintings, which I was completely blown away by, they are very cinematic and were shown in such a way at Victoria Miro gallery. Yinka Shonibare and his Cowboy Angel series, his graphic prints are made with a painterly expression. I fell in love with Helen Frankenthaler’s work a long time ago particularly her Mountains and Sea paintings, and more recently I have been looking at and reading about Georgia O’Keefe, as I am now exploring American Desert Landscapes.

Four things I took from my time at Camberwell, how to stick up for myself, how to draw and paint directly from observation, and how to listen to my own voice. The latter which I learnt from the painter Mario Dubsky has been the most useful tool as I know that is where authentic work comes from. With regard to sticking up for myself, I had to do that through resisting pressure from my (male) tutor to leave when I unexpectedly became pregnant at the onset of my degree.The skill of looking and working from observation has been another aspect I can work from at any time, its a wonderful skill to have.

Lastly I discovered Jung in my Psychology seminars which I attended along with Crime and Punishment in Film seminars, both of those subjects opened up my mind and were life changing.

Your paintings are known for their fierce irreverent energy and engagement with gender politics and film iconography. Can you walk us through your creative process, from the initial spark of an idea to working at scale in oils, acrylics and mixed media.

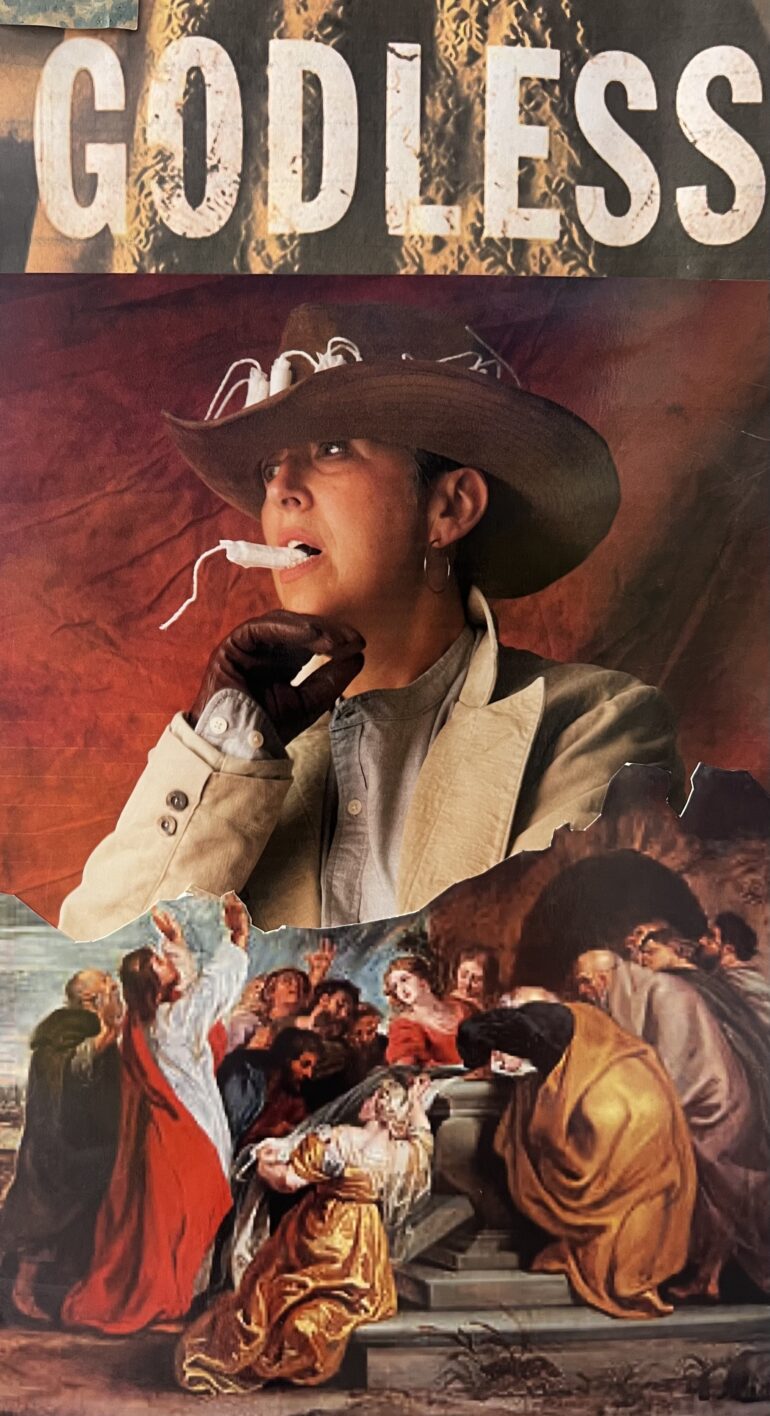

My creative process evolves and changes, I went through a period of exploring ideas through photographic collages, painted collages, small watercolours, very large felt tip drawings and large monochrome drawings in charcoal and graphite powder. Some of that work stands alone or led to larger works in oils, or watercolour and acrylic, I often will leave a painting and come back to it months or years later even. The photographic collages were constructed from photos I took in the Mojave Desert, Marlboro Advertisements, stills from films, Renaissance Paintings and my pre school granddaughter.

My current process is different, since early 2024 I have been working directly onto the canvas with no prep being made. I have a drive to explore with the medium of paint, often oils on large canvases as I want the physicality of painting to influence the outcome, I don’t know where it is going but I feel when it is right.

What does a typical working day in your studio look like? How do routine experimentation and physicality factor in to producing such visceral unrestrained work?

I usually start my 8-9 hour day in the studio around 10.00am and I am very aware of my first reaction to the paintings when I walk in, I then wash my brushes from the day before, giving me me time to think of how and where to start, I make a cup of something and then start the paint selection for my palette, I have very recently restricted my palette to four or five colours. I will select music to listen to whilst I work, but some days I work in complete silence. And sometimes I pull out a painting that has been knocking around for a bit and has stumped me and try some new application freeing it up to new possibilities by redrawing with oil sticks or paint. I also will turn paintings upside down to continue to work, and paint some un-stretched canvases on the floor where I can move all around it. Often I work at speed on up to 6 canvases all hanging on the studio walls, I take a break and go for a walk by the Grand Union Canal to be in Nature, or eat lunch in the kitchen away from work in the studio.

Looking back over your career, which exhibitions are you most proud of and why do they stand out in terms of personal, political or artistic significance?

There are three exhibitions that have significance for me, an Open Show at The Millfield Gallery in the 1990’s when I had my painting hung next to a John Bratby painting, I won 2nd prize and it gave me confidence to continue.

The second was my first London solo show at The Belgravia Gallery when Sir Christopher Frayling came and gave a brilliant talk about my work at the private view, and the third was another London solo show in 2023 @99projects gallery which was a body of work that truly set me on the road to where I am at now, and I met Frances Casey who was a joy to work with.

Your series Menopausal Cowboy powerfully explores perceptions of women in later life, drawing on Western Movies, horses and 20th Century Film and Iconography. What was the starting point for this series and where will it develop next?

The starting point came after a show I had at Carey Blyth Gallery in Oxford in 2024 where the paintings were primarily about horses, I decided I wanted an older female rider to be centre stage on the horse and to bring the image ‘To The Front’, once I had made two (they are all 5’ x 4’) I felt so excited I decided I was going to paint 12 so far I have made 10, these are very more direct paintings, in their execution but also in their viewing.

I want to combine these riders with my version of the Mojave Desert, I have started paintings of the desert some of which are titled ‘Dagger Trees’ the name given to the large yucca trees by the Mojave Native Indians, which are more commonly known to white westerners as ‘Joshua Trees’. These paintings are factoring in the ‘Yucca Moth’ as they and the ‘Dagger or Joshua Tree’ have a unique, obligate mutualistic relationship. Neither species can survive without the other and are both under threat by climate change. I stayed on my own for a time in the Mojave Desert and it was a life changing experience.

Find out more about Trish Wylie here.