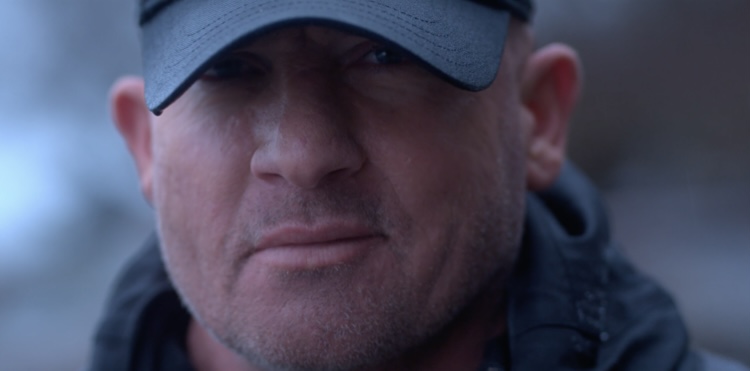

Culturalee interviewed Emmy Award–winning cinematographer and artist Mahlon Todd Williams, whose work spans acclaimed television series, feature films, documentaries and music videos seen by hundreds of millions worldwide. Williams most recently received international recognition for his work on the television series Fallen, adapted from the Number one New York Times–bestselling novel, which won an International Emmy Award in 2025. Yet beyond the camera, Williams has cultivated a parallel creative life as a painter, one that both complements and challenges his work in cinematography.

A native of British Columbia, Williams’ extensive credits include CW’s DC’s Legends of Tomorrow, the Syfy series Alphas, and the feature films Perfect High and Vendetta. Over the course of his career, he has travelled the world shooting documentaries, television series, films, music videos and commercials, developing a visual style shaped by both storytelling and technical precision. His fascination with filmmaking began as a teenager after watching a behind-the-scenes documentary on Raiders of the Lost Ark. With no family ties to the industry, Williams was nevertheless undeterred. Seeing how films were made and realizing that people could do this for a living, sparked a passion for the blend of narrative, craft and technology that defines cinematography.

Williams began by volunteering at a cable television station in Vancouver, shooting studio interviews and weekend sports broadcasts. He also picked up occasional work as a production assistant and appeared as an extra on The Boy Who Could Fly in 1986, an experience that cemented his love of being on set. A brief stint at stunt school clarified his ambitions further: he wanted to be behind the camera.

Williams went on to study film production at Concordia University in Montreal, where students were immersed in hands-on filmmaking – writing, directing, shooting and editing 16mm films. After advancing through the program and remaining in Montreal to work in the city’s independent production scene, he returned to Vancouver at a pivotal time, as the city emerged as a major production hub in the 1990s.

A self-described cinephile, Williams maintains a collection of around 400 DVDs, valuing not only the films themselves but the behind-the-scenes documentaries that reveal creative problem-solving, setbacks and happy accidents. He credits patience and persistence as essential to building a career, noting how seemingly small opportunities – an unexpected phone call or early collaboration – can shape years of work. One such relationship led him to major television projects and high-profile music videos, including promos for Drake and The Weeknd, with hundreds of millions of views.

Among his most ambitious projects is DC’s Legends of Tomorrow, a visually demanding series that required constant reinvention across time periods, stunts, locations and visual effects. His documentary work has taken him from Easter Island – filming projects broadcast in Canada, Japan and the UK – to Ireland, where he made multiple trips for a documentary on St. Patrick. In 2015, he reunited with longtime collaborator Jason Bourque on the independent feature Black Fly, a tightly budgeted production that relied on careful preparation and creative efficiency.

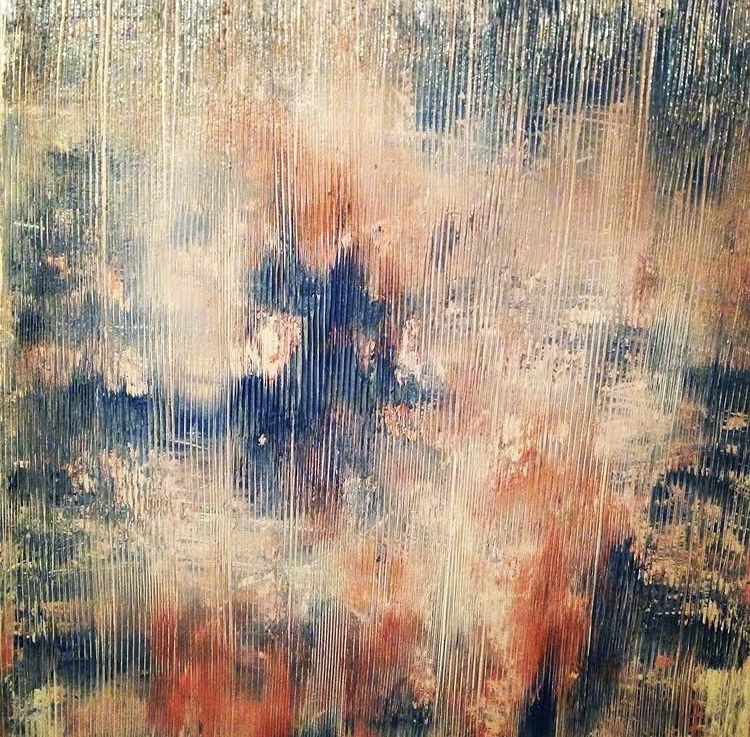

While cinematography remains central to his career, Williams has found balance through painting. Teaching himself to work with paint, he discovered it as a meditative way to unwind after long days on set, often going home from a shoot to continue creating on canvas. His paintings reflect the same sensitivity to color, light and composition that defines his screen work.

Williams has exhibited his artwork alongside stills from television episodes and films he has shot, revealing how specific projects influence his painterly choices. By pairing moving-image references with static works, he invites viewers to see how cinematic aesthetics translate into fine art. His work has been shown in Vancouver and London, with plans for both solo and group exhibitions in London in 2026. He is also exploring larger-scale photographic prints and experimental formats, including holographic imagery displayed on large screens.

In conversation with Culturalee, Williams reflects on how he decompresses after long shoot days by painting, how his experience as a cinematographer informs his artistic practice, which artists have influenced his visual language, and why presenting paintings alongside film stills feels like a natural extension of his career – one that continues to evolve across mediums.

Congratulations on your International Emmy win for Fallen, adapted from a Number One New York Times bestselling novel.What initially drew you to the visual world of this story, and how did you approach shaping the look and emotional tone of the TV adaptation through your cinematography?

Honestly, what first grabbed me about Fallen was that amazing mash-up of massive, eternal mythology and this super intense, personal romance. Lauren Kate’s books are obviously huge – they have this incredibly dedicated fanbase – so I knew right away that we had to honor the spirit of the series while finding a fresh, cinematic way to tell the story. The visual hook is that constant tension: you have this epic, cosmic stuff – fallen angels and celestial battles – but the story always boils down to raw, grounded, human emotions. This duality of light vs. shadow, big vs. small is exactly what a cinematographer lives for.

I started talking with creative heavy hitter Matt Hastings (our Director/Showrunner and the driving force behind the TV series) and Claudia Bluemhuber (the Producer who found the book and financed the TV Show). We deliberately stepped away from the cold, mysterious tones of the old feature film. We wanted to create a world that felt deceptively beautiful, almost too welcoming at first.

- The Sunshine Deception: A perfect example is Luce’s arrival at Sword and Cross. Instead of making it look spooky, we doused the place in warm, golden sunlight. This gave the detention center a false, comfy veneer. It instantly tells the audience, and Luce, that something is off—she’s being greeted warmly, but her gut says there are dark secrets hiding right behind that friendly light.

- Creating Tension with Color: To keep that underlying sense of unease and mystery, we constantly used color contrast in our lighting. We always aimed for a warm key light (to create that cozy, inviting look) paired with a cool fill light (to introduce shadows and an element of danger). This guaranteed there was always a subtle visualbattle happening on screen, perfectly reflecting the internal conflict of the characters.

- Intimacy Through the Lens: Since Luce is the heart of the show, we needed the audience to connect with her instantly. I had a little trick for this: the ARRI Signature Prime 29mm lens. We reserved that specific lens only for her close-ups.The actress has this incredible bone structure, and the 29mm was magic on her—it made her really jump off the screen. By keeping the camera physically close, we could capture every flicker in her eyes, ensuring the audience felt like they were right there with her, sharing every secret and every intense feeling.

Ultimately, my goal was to shoot an ancient, forbidden love story that felt both mythically huge and uncomfortably close-up at the same time.

You’ve travelled the world shooting everything from large-scale TV action like DC’s Legends of Tomorrow to intimate documentaries. How did your decades of experience – across genres, continents, and formats – inform your cinematographic decisions on Fallen? Were there techniques or instincts that felt like a culmination of your journey so far?

I absolutely feel that Fallen was a culmination—a project where all the different facets of my journey came together. It truly reinforced my core belief: story always comes first. My path to becoming a cinematographer started with a love of film, but practically, it was rooted in watching and later shooting I was initially hooked by things like the Raiders of the Lost Ark making-of doc, captivated by the fantastic locations, the huge stunts, and the intense drama.

This led me to research the legends who had shot the movies I loved—Masters like Haskell Wexler, Conrad Hall, Gordon Willis, Roger Deakins, and Robert Richardson. I noticed a clear through-line: many of them started their careers in the documentary world.

Instinct and Execution: Documentary work teaches you to live through real events. You learn skills on the road that allow you to read a situation instantly and figure out how to place the camera in the single best position to tell the story. Crucially, this often happens in real-time, with no second chances to capture a spontaneous, authentic moment.

Applying the Instinct: I use that skill every single day on set, especially while watching an actor rehearse a scene. That documentary instinct allows me to react to the performance, rather than imposing a preconceived plan. On a series like Fallen, this meant quickly finding the composition that best highlighted the intimate, fated connection between the characters.

Fallen needed that blend of instinct and scale. My experience on a large-scale action show like Legends of Tomorrow gave me the confidence to manage the logistics of sweeping locations and complex camera moves, while the documentary discipline ensured every single frame felt authentic and grounded. Ultimately, the look of a film should always be grounded in the story you are telling. I believe great cinematography blends seamlessly with the narrative. The style of the film, whether it’s grand action or intimate romance, will organically find its way through the dedicated process of telling the story. Fallenallowed me to use all my tools—from high-pressure, technical proficiency to quiet, observational framing—to capture that unique balance of epic myth and personal emotion.

After long shoot days, you often unwind by going home and spending hours painting. What does that transition from the high-pressure environment of a set to the quiet of a canvas give you, creatively or emotionally?

The transition from the set to the canvas is my necessary creative and emotional reset. These two worlds operate on completely opposite clocks. On set, my mind is governed by an internal clock that never stops. I am constantly calculating how little time we have. As we say, “plan your work; work your plan,” but that plan is always being adjusted. While maintaining that necessary structure, I’m always trying to keep myself open to “happy accidents”—finding an unexpected angle or a beautiful lighting detail based on sheer instinct. That requires intense, focused energy and continuous critical assessment.

When I go home and pick up the brush, my goal is to shut down that inner critical voice. Painting is the emotional release that frees me from the stress and calculation of the day. I can start a painting, and in what feels like a blink of an eye, an hour or two will pass. The combination of the day’s events and my sheer exhaustion seems to help open the gateway to pure, unfiltered creativity. I feel instantly calm and transported to a purely creative, non-judgmental space. My paintings tend to have a lot of movement and color—it’s an almost unconscious release of the energy I held onto all day.

What’s fascinating is the detachment that sleep brings. I leave my paintings on the floor to view in the morning. I find that my connection to each piece fundamentally changes after a good night’s rest. Something I wasn’t happy with the night before often reveals itself to have a stronger, more powerful connection the next morning. I also love the public side of this: walking around my exhibits and hearing people talk about which paintings they connect with, and why. It constantly amazes me how what I see and feel about my art is completely transformed by the viewers. Each person’s theory about the work holds as much power as the next, and that reminds me to always value subjective interpretation—a useful lesson when working on collaborative storytelling like a TV series.

Your paintings have a distinctive visual language. In what ways does your cinematographer’s eye – your sense of color, lighting, composition, or movement – influence the way you paint? Do you find that the two practices feed each other?

Absolutely, the two practices feed each other constantly. Having spent 30 years in the film industry as a camera assistant and cinematographer, the core principles of visual storytelling are now completely ingrained, and they transfer directly to the canvas.

My journey began at Concordia University and the late ’80s Montreal film community, which captivated me. Films like Jean-Claude Lauzon’s Un Zoo La Nuit and Léolo, shot by Guy Dufaux, had an energy and visual power that excited me, even though I didn’t speak French. That experience, and the thrill of sitting in a cinema and being swept away by Hollywood epics like Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Untouchables, initially sparked my passion.

However, it was the start of home video that truly burned the technical language into my brain. Having Vittorio Storaro’s use of color and light in Apocalypse Now on repeat cemented my love for cinematic color and composition—the long takes, the constant flow of framing, and the power of the moving camera.

Today, my paintings are essentially a direct, instinctual expression of my cinematographer’s eye:

Depth and Focus: Just as a shallow depth of field guides the viewer’s focus on screen, I use that technique in my painting. I blur backgrounds to create a feeling of spatial depth, ensuring the viewer’s eye is immediately pulled toward the detail I want to highlight.

Layered Color and Lighting: I love color, and I tend to layer my paintings with intense color. I also use complementary colors to enhance the feeling of depth, the same way I would use opposing color temperatures while lighting a set. My instinct when lighting is to work back-to-front, placing bright, sometimes “burned-out” highlights deep in the background to give life and texture to the image. I replicate this by often starting my paintings with bright underlayers and finishing with dark ones.

Backlight Philosophy: This technique is similar to backlighting an actor and allowing the shadow on the camera side of their face to create drama and mystery. It is a fundamental method for giving the image life and guiding the viewer’s attention.

The connection between the two experiences is the immersive quality. Watching a movie on a big screen is a fully immersive experience. It feels exactly the same as walking into a large exhibit room with one large, powerful painting hanging on the wall—it emotionally pulls you in and fully engages your senses. Both the camera and the brush are tools for achieving that powerful, absorbing connection.

You’ve exhibited paintings alongside stills from the TV episodes or films that inspired them. Why is that dialogue between frame and canvas important to you, and what do you hope audiences see when they view your paintings in conversation with your cinematography?

For me, the dialogue between the frame and the canvas is vital because the two practices are so intertwined, I don’t think I could have one without the other.

I never intentionally set out to create a painting that matched the work I shot that day. But the emotional impact, the specific color choices, and the rhythm of movement from the set are deeply baked into my DNA. Being able to release that focused energy in another format, through the freedom of the brush, is incredibly calming and necessary. I honestly surprised myself when I started to match the still frames from the production with the paintings I had created during the same period. The visual and emotional synergy was undeniable.

The Subconscious Link: Sometimes the connection is obvious — a direct color match or a similar dynamic movement. Other times, the connection is purely atmospheric, demonstrating how the day’s cinematic goals subconsciously shaped my choices on the canvas.

This conversation is an endless circle of inspiration. When I’m in a new city, I spend hours walking through art museums, searching for new painters and styles that emotionally engage me. I actively try to remember the feelings I get when viewing those masterworks and then attempt to replicate that emotional resonance on set with my lighting and framing.

By exhibiting the painting alongside the still, I invite the viewer into that discovery process. They can appreciate the painting on its own terms, or they can see the selected still frame and create the links between the two. Each person’s visual theory—whether they see a color relationship or a shared emotional tone—holds value, reinforcing that powerful, subjective connection we always strive for in visual art.

As a self-taught painter, you’ve developed a unique aesthetic. Which artists – painters, photographers, filmmakers, or even DPs – have most influenced your artistic voice, and in what ways do they shape your approach to both your cinematography and your fine art?

My aesthetic is a direct result of constantly drawing inspiration from a wide variety of influences across different visual disciplines. As a self-taught painter, I’ve had the freedom to pull techniques from wherever I find genuine emotional and visual power.

Specific cinematographers provided the technical blueprints for my approach to light and composition:

Conrad Hall (e.g., Searching for Bobby Fischer): Hall’s genius was his use of controlled lighting that appears incredibly natural yet powerfully dramatic. His specific techniques—like the frequent use of hot highlights positioned deep in the background of the frame, combined with a shallow depth of field—are foundational to my work. These methods create depth, draw the eye, and are principles I directly apply when composing and lighting a set, as well as when creating focus and layering in my paintings.

Douglas Slocombe (Raiders of the Lost Ark): Slocombe’s bold use of hard, direct light captured my attention early on. This technique creates high-contrast shadows and texture that amplify the drama and scale of an action adventure, giving the frame an immediate, dynamic energy that I carry into my own work.

Robert Frank’s The Americans: This book is a masterclass in telling complex, powerful stories through a single frame. This informs my cinematography by demanding that every still composition—every pause in movement—must be able to stand alone and convey narrative depth.

Gerhard Richter’s Abstracts: Richter’s use of scale and texture is always profoundly moving when experienced in person. His work shows me the emotional power of abstract movement and layering, which directly translates to my painting style and my use of complementary color layering in my lighting schemes.

Winslow Homer’s The Herring Net (1885): Homer is a huge influence, specifically for his extraordinary use of color and contrast. The way he juxtaposes light and dark, warm and cool tones to define the drama is a constant lesson in how to make an image feel physically tangible.

Rembrandt and Basquiat: My work is also deeply informed by Rembrandt’s ability to compose high-stakes action (The Storm on the Sea of Galilee) and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s vibrant use of symbols to layer meaning and texture.

In short, every piece of art I’ve named teaches the same lesson: how to use light, color, and composition to engage the viewer’s emotions. Whether I’m placing a key light on a set or blending pigments on a canvas, I am always channeling these masters’ instincts for creating power, drama, and connection within the frame.

Find out more about Mahlon Todd Williams here.

Watch the Fallen trailer here.

The transition from the set to the canvas is my necessary creative and emotional reset. These two worlds operate on completely opposite clocks. On set, my mind is governed by an internal clock that never stops. I am constantly calculating how little time we have. As we say, ‘plan your work; work your plan’. But that plan is always being adjusted. While maintaining that necessary structure, I’m always trying to keep myself open to ‘happy accidents’ —finding an unexpected angle or a beautiful lighting detail based on sheer instinct. That requires intense, focused energy and continuous critical assessment.” Mahlon Todd Williams