Following renewed public interest sparked by last year’s biopic LEE, starring and produced by Kate Winslet, Tate Britain presents the first major UK retrospective of Lee Miller’s photography, an exhibition that feels not only timely but corrective. Long celebrated as a muse, model and surrealist insider, Miller is finally positioned where she belongs: as one of the 20th century’s most urgent, inventive and fearless photographic artists.

The expansive exhibition, simply titled Lee Miller, traces the full scope of her extraordinary career, from her early involvement in surrealism to her pioneering work as a fashion photographer and, most significantly, as a frontline war correspondent during the Second World War. Comprising around 250 vintage and modern prints – many never before displayed – the retrospective offers a powerful reappraisal of an artist whose poetic vision and moral courage shaped modern photography.

From in Front of the Lens to Behind It

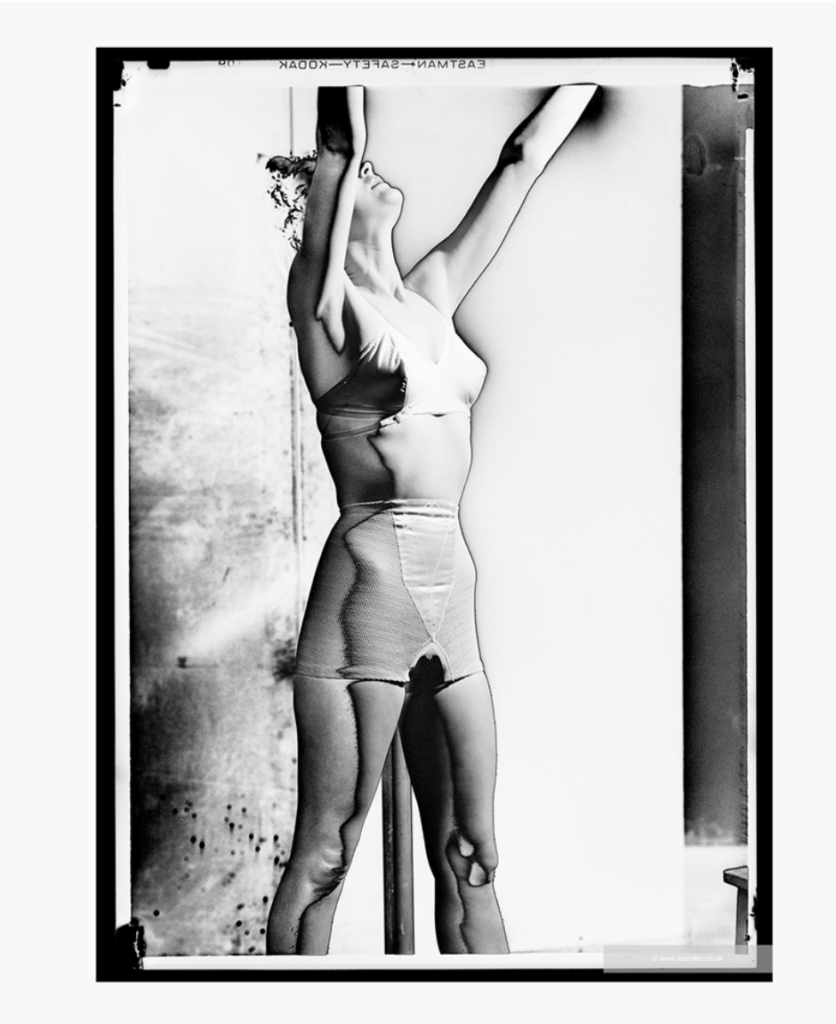

Lee Miller’s introduction to photography came, famously, from the “wrong” side of the camera. One of the most sought-after models of the late 1920s, she embodied the modern woman – striking, independent and unapologetically intelligent. Her career was launched almost by accident in 1927, when Condé Nast reportedly saved her from being hit by a car outside Vogue House in New York. The encounter led to her first Vogue cover that same year and swiftly established her as a fashion icon.

Yet Tate Britain is careful not to linger on this familiar narrative. Instead, the exhibition foregrounds Miller’s deliberate decision to step behind the lens, a move that marked the most radical and creatively fertile chapter of her life. As the show makes clear, Miller did not abandon modelling so much as she absorbed it, using her deep understanding of pose, performance and visual construction to develop a singular photographic language.

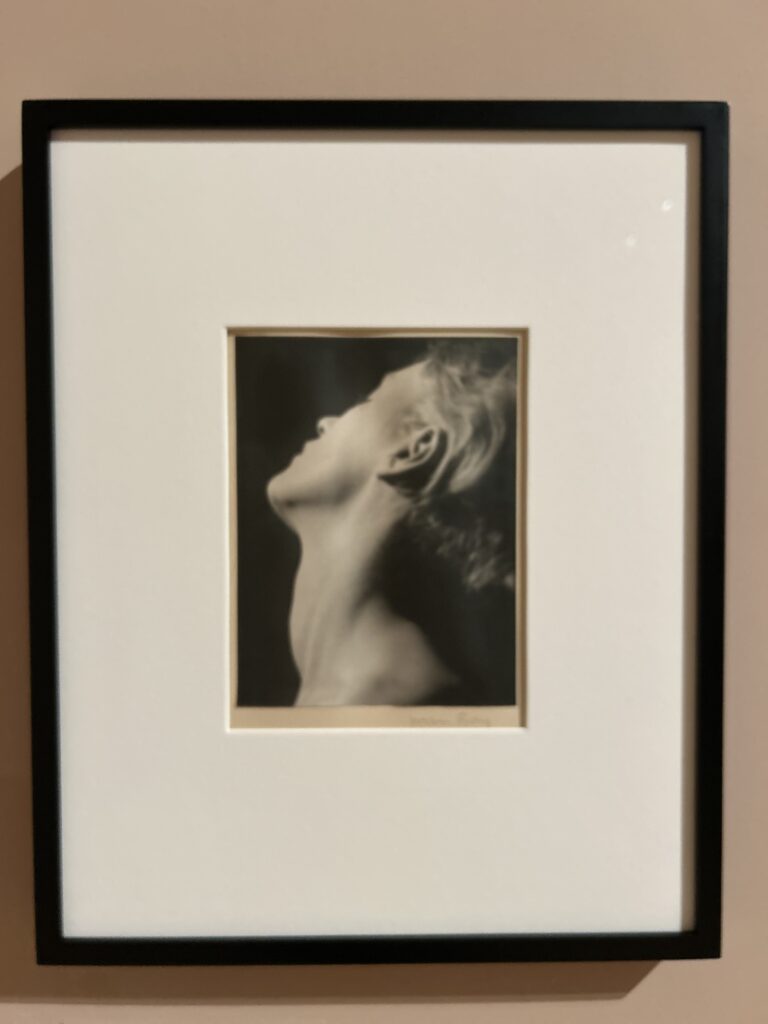

Her early work situates her firmly within the Avant-garde circles of New York and Paris, where she collaborated closely with Man Ray. While history has often reduced Miller to the role of “muse” within surrealism, Tate Britain decisively challenges this framing. There is strong evidence – long discussed but rarely institutionalised – that Miller was instrumental in developing the solarisation technique frequently attributed to Man Ray alone. Here, her experimental brilliance is treated not as footnote but as fact.

Collaboration, Not Musehood

As curator Hilary Floe writes in the exhibition catalogue, Miller’s legacy has too often been obscured by a media obsession with her beauty and her relationships with celebrated men such as Man Ray and Pablo Picasso. This retrospective instead emphasises her collaborative intelligence and artistic agency. Miller was not merely a participant in creative networks; she was a catalyst within them.

Her work is marked by what Floe describes as “sensitive co-creation”, whether performing for another’s camera, working side by side with fellow photographers, producing searching portraits of artists, or crafting photo-stories for editors such as Audrey Withers and Ernestine Carter at British Vogue. Miller’s photography thrives on porous boundaries: between genres, between authors, and between art and reportage.

Rooms devoted to her surrealist work demonstrate this fluency. Objects are dislocated, bodies fragmented, scale distorted. Particularly striking are her photographs made in Egypt during the 1930s, where vast desert landscapes become dreamlike terrains, at once serene and uncanny. These images, lesser known than her wartime photographs, reveal Miller’s capacity for quiet metaphysical inquiry and visual poetry.

Recent approaches have focused on Miller as a successful professional photographer, productively exploring and documenting her published journalism: this ranges from the Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum’s 2023 exhibition Lee Miller in Print to the 2024 feature film Lee, which centred on Miller’s war reportage. While enriched by the research that underpinned those projects, this exhibition, in contrast, spotlights Miller the artist. Doubly marginalised from the art world as a woman and a photographer in an era in which photography’s status as an art form was marginal at best, Miller’s work incorporates genres such as advertising, portraiture, fashion, still life, landscape and photojournalism, but is not bound by them.” Hilary Floe

Fashion, War and the Refusal to Look Away

If Surrealism gave Miller a language of disorientation, war gave her a moral imperative. Determined to prove herself in a field that remained aggressively male-dominated, she pushed relentlessly toward the front line. Miller became the only female photographer accredited as a war correspondent during the Second World War, documenting the Blitz in London before following Allied forces across Europe.

The Tate Britain exhibition moves chronologically and emotionally toward its most devastating material. Rooms devoted to wartime London show Miller’s ability to balance formal composition with raw immediacy: bombed buildings become abstracted ruins; civilians appear both resilient and shell-shocked. These images already mark her refusal to sanitise conflict, but they are only a prelude to what follows.

One of the exhibition’s final rooms – preceded by a content warning – contains the photographs Miller made after the liberation of Nazi concentration camps. Miller and her colleague David E. Scherman were among the first journalists to enter Auschwitz and Dachau following liberation in April 1945. What Miller encountered there would haunt her for the rest of her life, contributing to the post-war trauma that ultimately silenced her practice.

Her photographs from Auschwitz are unflinching. Survivors stare directly at the camera; corpses lie in grotesque stillness; the architecture of genocide reveals itself in cold, functional detail. These images were commissioned by Vogue, yet they defy the conventions of magazine photography. They exist instead as historical testimony, records of atrocity made by someone who believed, fiercely, that looking away was not an option.

Hitler’s Bathtub: An Icon Recontextualised

The most famous image in the exhibition – Miller bathing in Adolf Hitler’s private bathtub – appears here not as spectacle but as reckoning. Taken on April 30, 1945, in Hitler’s Munich apartment (then an American command post), the photograph shows Miller seated calmly in the tub, her army boots placed deliberately on the pristine white bathmat. The boots are caked with mud from Dachau, which she had documented earlier that same day.

A small portrait of Hitler, repositioned from another room, leans against the tub’s edge. The symbolism is unmistakable. Coincidentally, Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide in Berlin on the very day the photograph was taken. Miller was, quite literally, washing the filth of the concentration camps from her body in the dictator’s own home.

Her son later described the image as an act of defiance, victory and moral clarity. Seen within the context of the exhibition, the photograph reads not as irreverence but as indictment. It is the culmination of Miller’s wartime work: an image that collapses personal endurance, political triumph and historical witness into a single frame.

Reclaiming an Artist

The final sections of the exhibition reinforce what this retrospective achieves so powerfully: the repositioning of Lee Miller not as an accessory to history but as its author. Doubly marginalised in her lifetime as a woman and as a photographer in an era that still questioned photography’s status as art, Miller refused categorisation. Her work traverses advertising, fashion, portraiture, still life, landscape and photojournalism without ever being bound by them.

Miller’s own words echo through the exhibition like a manifesto: “It was a matter of getting out on a damn limb and sawing it off behind you.” Tate Britain’s retrospective honours that ethos. It does not sentimentalise Miller, nor does it reduce her to trauma. Instead, it presents a complex artist whose bravery lay as much in her vision as in her actions.

Lee Miller at Tate Britain is not simply a long-overdue retrospective; it is a reclamation. It insists that Miller be seen whole: surrealist innovator, fashion photographer, war correspondent, collaborator, witness. In doing so, it reshapes the canon of 20th-century photography, and reminds us of the cost, and necessity, of truly looking.

Lee Miller is on view at Tate Britain, London until 15th February, 2026.

Organised by Tate Britain in collaboration with the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris and the Art Institute of Chicago.

More information here.